III. THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME

“Doomsday is near; die all, die merrily .”

Henry IV, Part 1 (4, i)

Foreshadowing occurs throughout L'eclisse with frequent clues pointing to the final eclipse of the film. It is as if the entire film were the approaching shadow cast by an eclipse as it passes over the Earth, an umbra mortis (Latin, from the Hebrew, צלמות), the shadow of death. Adumbration, particularly of a dark foreboding nature, approaches becoming a central motif or organizing principle of the entire film. The very first image of L'eclisse is that of a white, vertical line against a black background upon which the film credits will appear. (The line erases itself--or to use a term suggested by Brunette--becomes “unzipped” at the conclusion of the credits, as do Vittoria and Piero at the end of the film. Instead, one might say that, like a spurned love letter, the film has been ripped in two.) Although this vertical line may at first seem innocently decorative, the line instead heralds the appearance of the strong vertical lines that will incessantly appear throughout all of L'eclisse, such as the pillar of the Borsa that will soon separate Vittoria and Piero upon their very first meeting. We have already seen how the brief interaction between Piero and the secretary, Maria, anticipates the very sunset of L'eclisse. (The scene in Piero’s office at end of day eerily resembles that of the Hopper painting, “Office at Night.”) Indeed, during the first encounter between Vittoria and Piero at the Borsa, simultaneous with Piero’s introducing himself to Vittoria, a buzzer sounds interrupting their presentation to one another, announcing the minute of silence for the dead stock market broker.14 Thus, the introduction of the two central lovers of the film is coincident with an announcement of death.15 For Vittoria and Piero, meeting is already parting. In our beginning is our end. The very first private conversation Vittoria and Piero have—when they “accidentally” meet at the Bar della Borsa—is about loss. Vittoria repeatedly asks Piero where the money in the stock market crash has gone, a silly, tragic conversation between two people who do not yet know that they too are destined to soon disappear from their own movie and lose one another forever. Piero formally initiates his “courtship” of Vittoria on the very day of the stock market crash when in the evening, after dumping (“slaying”) the Bestiola, he impulsively drives to Vittoria’s apartment. Psychologically, Piero may be seen as trying to assuage his financial loss with a sexual anodyne, the wrong cure for the wrong illness, for it is ultimately an empty life of vanity that Piero must but does not know how to treat. It is doubtful that a man such as Piero even suspects that his life might be empty. Sandro of L’avventura is little different from Piero of L’eclisse insofar as Sandro repeatedly and unsuccessfully applies the incorrect balm, sex, with women he does not love, for his failure to become the architect—the man—he once desired to be. Sleeping with a woman whom you do not know, striving to become rich in labor that is not rewarding in the deeper sense of the word, or travelling to an exotic, faraway, vacation hot spot will not repair a broken life.

At each step of their relationship, signs point to the ominous prognosis for their union. Ironically, it is in their very last encounter in Piero’s office, when there is a loving and playful tone to Vittoria and Piero’s interaction--a time when they pledge to continue seeing each other for all the tomorrows to come, and when their prognosis seems to be for once the most genuinely promising--that Vittoria and Piero are actually taking their final leave of one another. This is a very common phenomenon in literature and cinema that may be referred to as “the quiet before the storm” motif: Just when the plot has settled down and things seem to be at last going well for the characters of a particular book or film, the book reader/film viewer should suspect that a catastrophe is imminent. (Caution: Plot Spoiler) In the case of Naruse’s masterpiece, Ukigumo (Floating Clouds) [1955]--one of the most heart-rending doomed-love stories of the cinema (concerning but one more tragic aspect of the human condition that is sometimes referred to as “erotic melancholia”)--there is literally “quiet before the storm” on the Japanese island of Yakushima before the tempestuous climax of the film. The opposing literary/cinematic device--the contrary phenomenon to “the quiet before the storm”--is the “it’s always darkest just before the dawn” conceit.

The opening film credits are not only a foreshadowing of things to come, but a summary of the entire film. It is not just that from a visual standpoint the credits zip and unzip themselves. Acoustically, the credits begin with the pop song, “Eclisse twist,” sung by the Italian mega-pop star, Mina, which are suddenly cleaved mid-way and replaced by the very music of Giovanni Fusco that will conclude the film. Such an interruption and replacement of the title song of a film is highly unusual and seemingly inexplicable. And yet, the replacement of a pop, love ditty by a succession of ominous piano octaves captures the arc of Vittoria and Piero and all of L'eclisse. Such an employ of music is characteristic of the extraordinary use of sound in all of L'eclisse which I discuss in greater detail in Endnote 27 .*

Antonioni had played with ominous adumbration before. Shortly after Le amiche begins, we witness Clelia drawing a bath--a typical Antonionian preoccupation with water--that anticipates the later drowning of Rosetta in the Po.

At times, the signs pointing towards the future may appear to pass as fleetingly as do the warning signs alongside a freeway. A fan continuously rotates back and forth on its base in the opening scene of L'eclisse (its movement offering a simulacrum of a living being). Its humming sound--the speech of machines--is present throughout the scene, to be joined later in the scene by the buzzing sound of Riccardo’s electric razor in a bitter duet of mechanical noises. The sight and sound of the fan are insistent, at one point blowing Vittoria’s hair as if it were the wind in the trees. (A ceiling fan also gently blows the hair of both the living Locke and the dead Robertson as Locke bends down peering into Robertson’s eyes on their shared death bed.) Towards the conclusion of the opening scene we see that the fan is no longer moving either side to side, either suddenly broken, or turned off by an unseen hand in an ellipse. (Although the fan blade itself seems to still be rotating, is its humming sound still present in the background? In Blow-Up, at one point we hear the wind of Maryon Park inside the Photographer’s studio.) This fan anticipates the rotating sprinkler of the Eur, an “animate” lifeless contraption that will also be turned off or “extinguished” in the coda of L'eclisse. The turning off of both fan and sprinkler heralds the stasis that reigns at the conclusion of L'eclisse, a stasis that will itself be extinguished when the cord is finally pulled on the film itself, and the screen again turns white, a white-out more blinding than that of the white street light in L'eclisse’s final burst.

A particularly ironic foreshadowing--one that is also a warning--occurs in a seemingly banal moment of conversation in Marta’s apartment. Marta is talking to Vittoria of her life in Kenya and her encounters in Africa with elephants. Vittoria asks Marta if she is afraid of such wild animals to which Marta replies, “No. . . . Hai paura te delle macchine?” / “No. . . . Do you have fear of cars?” (incidentally, also reinforcing the equivalence of living creatures and lifeless things). Vittoria leaves the rhetorical question unanswered, but it is only scant cinematic minutes away before a car becomes Death’s coach in L'eclisse.

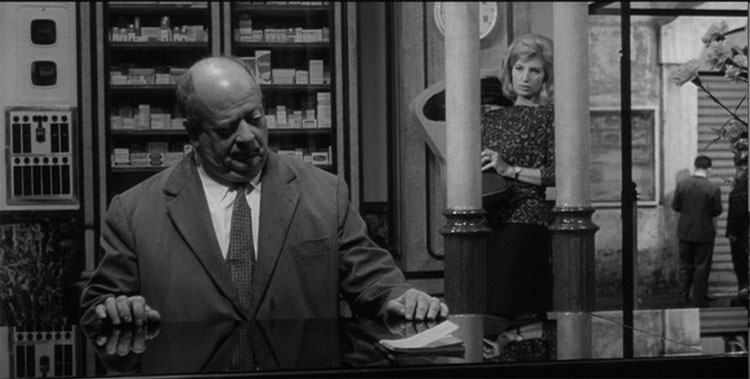

Another fleeting sign in L'eclisse that points to a future event in the film passes so quickly that it, too, might easily be missed. After the collapse of the market, Vittoria, for no obvious reason, follows to a pharmacy the obese trader who has lost an enormous amount of money. At the pharmacy the man--whom presumably Vittoria does not know--purchases a mild “tranquilizer” (an over-the-counter medication, “Perequil”). To screen right of the obese man as he purchases the Perequil, a large bouquet of flowers sits on the pharmacy counter. Characteristically, the flowers are wedged between two pillars, as is Vittoria who stands on a scale in the background spying on the man. (Vittoria’s left forearm which bears her wristwatch has been severed below the elbow and is reflected in the shiny pharmacy countertop, almost touching the left hand of the obese man [see filmgrab below]). Although unclear, the flowers may be white garofani (“carnations”), flowers commonly associated in Italy with funerals (as in Germany such flowers may also be referred to as “Todesblumen,” “flowers of death”). Immediately after leaving the pharmacy, the man will begin doodling small flowers on a piece of paper as he sits at an outdoor café.

A matter of scale

It is, however, after the theft of Piero’s body and car by the Drunkard that a remarkable flurry of images and events take place that are linked with the principle of adumbration. The morning after the car theft, we see the phantom image of the white (ghost-like) Alfa being hoisted by a crane out of the Eur lake (a body of water that is itself artificial, intended for events such as canoeing and rowing in the 1960 Olympics). There is an extended shot taken from the vantage point of the lake itself of the Alfa rising out of the water, flying as it were. Curiously, it was necessary for Antonioni to place his camera upon a platform in the lake itself, the final resting place of the Alfa, a shot taken from the perspective—the POV—of a dead man. A single headlight, that of the passenger side, is still illuminated, a strange phenomenon when one considers that the car has presumably been submerged for at least several hours, if not much of the night (suggesting, among other things, the primacy of dead things over living beings; i.e. the car outlives the Drunk).

Clearly, Antonioni went to a great deal of difficulty and expense to achieve such an image. The original screenplay contained in John Francis Lane’s book L'eclisse di Michelangelo Antonioni specifically refers to the illuminated headlights of the Alfa creating a spectral appearance shining from beneath the surface of the water as the car is raised from the lake. (Antonioni describes the image as “magica” in the screenplay.)* In the script, before Vittoria is told by Piero that there is a dead man in his car, she is struck by the beauty of the scene, the terrible loveliness sometimes dictated by the aesthetics of violence. The actual scene was shot in a different manner. During the first attempt to film the Alfa being hoisted from the water, the cable snapped sending the car again beneath several meters of water. Antonioni then sacrificed both his desire to shoot the scene at sunset, and also Vittoria’s utterance of “stupenda” invoked by the beauty of the scene.

In the scene that was ultimately shot at midday, the one headlight that does remain illuminated anticipates the streetlight at the very conclusion of L'eclisse, an image which like that of David Hemmings in Blow-Up, disappears in the final seconds before the film is itself extinguished.* Like a theater curtain, the car is slowly raised high in the air by the crane. If we look carefully, we witness Vittoria and Piero as they are unveiled near the very center of the frame beneath the bumper of the Alfa and its shiny reflection of a rising Roman Sun—a halo burst of light—inconspicuously placed amidst the crowd of onlookers, “Galgenvögel” or gallowsbirds. Immediately next to Vittoria and Piero, the sharp, vertically-oriented image of a single, tall streetlight rises from the center to the top of the frame, the dome of the Church of Santi Pietro e Paolo visible yet further in the background. Not to be overlooked are at least two Italian cypresses visible rising in screen right, Cupressus sempervirens, also known as “graveyard cypress” or, as Scottie in Vertigo would someday say, always green, ever living. Gaze intently enough and you will see everything, everywhere. This is, perhaps, Antonioni’s greatest strength as a man who made movies: He beckons us to look, if even at the end there is nothing to look at . . . at all. The deadend conclusion of L'eclisse: an utterly black screen which in turn disappears, leaving us only with a half-torn movie ticket and a little love affair also ripped in two that we thoughtlessly discard among the buttered popcorn, candy wrappers with their little fortunes of Foscolo, and spilt soda pop on the cinema floor.

Picture-Perfect Place Setting

Darkness at Noon

That none be exempt from Judgment, even the sea and all the waters shall give up their dead. Revelation 20:13

There is, thus, a momentary juxtaposition--receding sequentially in the distance--of the wrecked Alfa and the Drunkard, Vittoria and Piero, the streetlight, and the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul. (This tableau “vivant-mort” incorporating Vittoria in the same frame with the dead Drunkard is consonant with the Renaissance motif of “Death and the Maiden”; by film’s end the issue will not, however, be limited to only that of Vittoria and Death, but to that of Death and the World.) Indeed, the composition of this shot is so carefully painted that in freeze-frame there is a moment when the Drunkard’s right hand is literally superimposed over the left hand of Piero, the two soul mates touching one another. (The right hand of both Piero and the Drunkard had also been previously superimposed in a “metaphysical high-five” in the earlier scene when the Drunkard speeds dangerously past Piero after the Drunkard has stolen Piero’s car; see filmgrab, Chapter IV.) 16 A dissonant carnival atmosphere prevails. The death of the Drunkard is comically reprised (“doubled”) as an onlooker accidentally falls into the lake as the other onlookers who will soon die as well begin to wickedly laugh, a dead man hung above them all, a nasty spasm of Schadenfreude (reminiscent of the party and swimming pool of La notte).*

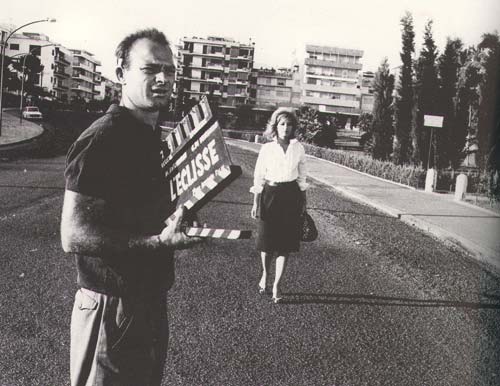

Madcap antics and boyish hijinks while filming a love story regarding doomed love

at Death’s doorstep to the Inferno

Vittoria and Piero then leave the scene at the lake to begin a promenade that appears unmotivated and purposeless, and that yet constitutes one of the central episodes of the entire film. Because their aimless walk serves no obvious conventional narrative purpose such as linking one scene with another, the episode constitutes a kind of “parenthesis” or “trou dans le temps” (a term that has been applied to certain scenes that occur regularly in the films of Rohmer). To again employ a French term that Brunette uses, the “flânerie” of Vittoria and Piero resembles other apparently aimless wanderings that Antonioni enacts, particularly the meandering exploration of Milano by Lidia in La notte. Such ambulating solves nothing, and is indeed, contrary to the entire principle of “solvitur ambulando” (Latin for, “It is solved by walking.”)

Slouching towards Bethlehem to a fatal encounter that will expire at The End

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a ciac.

Early in their balade, Vittoria and Piero stumble upon the peculiar, outdoor “piano bar,” the only apparent patrons of which are an elderly couple. After then exiting the bar, we next see Vittoria and Piero running (“in a big hurry to go nowhere”*) along a deserted street in the Eur towards an empty baby carriage, the nursemaid of which has also disappeared. Attached to the carriage is a child’s balloon. (It is difficult to view the scene painted on the balloon, but in freeze frame it is clearly a cartoon-like caricature of a man smoking, something that we see Piero, but not Vittoria, doing shortly thereafter at the water barrel.) Unexpectedly, we then discover that we are at the foot of Marta’s apartment building. Vittoria then steals the baby’s balloon and yells up to Marta requesting that she grab her rifle (which has already been used to kill elephants and hippos) and shoot the balloon.17 The bubble is then literally burst, the cartoon figure vanishing like so many of Antonioni’s protagonists into thin air, a puff of smoke not unlike the puffs of smoke painted on the balloon itself (the balloon thus hinting at its own destruction).*

As Vittoria and Piero walk away from the apartment towards their fateful intersection, we hear the disembodied voice of Marta on the soundtrack saying, “goodbye.” (Only minutes earlier the mute hand of the dead Drunkard had also waved goodbye, dangling from the Alfa as it is hoisted from the water. Tu fui ego eris; what you are, I was; what I am, you will be.)*

Addio . . .

We then view the couple from in front as they walk, and witness Vittoria buttoning an unfastened button of her blouse (through which Piero had earlier glimpsed her breast), anticipating her final denial of Piero at the conclusion of the film. (In their final scene together, while frolicking on the floor ofPiero’s office, Vittoria adopts the identity of a tigress. A buzzer rings--someone at the front door--but no one is there.* Time is up, or time has run out, or time will have its way. Vittoria stands up and then takes a chain, ostensibly a necklace, and places it around her neck. She has again buttoned herself up and again sealed off her existence, this time forever.)

Continuing their walk through the Eur, Piero then utters an explicit prediction, informing Vittoria that he will kiss her when they finish crossing the street before them. Vittoria and Piero are then filmed from behind, faceless, as they cross the empty intersection, the zebra lines of the pedestrian “crossing” barring their way. They stop in the middle of the street as Vittoria observes, “Siamo metà” (“We’re halfway there.”),* suggesting a larger sense of incompleteness. Having traversed the intersection, they now stand by a wooden fence next to the construction site of a half-finished building. After several awkward moments, Piero’s prophesy comes true, its fulfillment being the most tentative and incomplete of grim embraces. He tries again to kiss Vittoria, the attempted kiss this time completely denied, an expression of foreboding written upon her face. An anonymous pedestrian walks by interrupting the action. Ominous music is then heard without any apparent source in the immediate environment of Vittoria and Piero, the same extra-diegetic music that repeats itself at the very end of the film. Vittoria then breaks off the small piece of wood from the fence, perhaps the single most important unimportant object of L'eclisse, and throws it into the barrel. A stranger rides by on a bicycle. Vittoria and Piero take leave of each other. As they retreat from one another, Vittoria turns to look back upon Piero, the fatal movement committed by Orpheus. Piero is nowhere to be seen.

This then, is the beginning, the springtime of Vittoria and Piero’s romance. The above sequence heralds the final eclipse of the film, the blotting out of both Vittoria and Piero. (An analogous scene occurs towards the conclusion of The Passenger when, David Locke, the Jack Nicholson character, crushes an apparent leaf--or perhaps an insect--on a wall, anticipating his own imminent death.)* Death, destruction, denial, negation, violence, incompleteness, and desolation characterize many of the individual events of the sequence in L'eclisse just described. Thus, as opposed to most conventional cinematic depictions of the stirring of newborn love between a man and a woman, we are instead shown a couple whose courtship might as well have taken place in a divorce court or morgue. Although one might simply sigh, “these two just aren’t going to make it,” another thought--that of a single word--comes to mind. Doom.*

L'eclisse may be seen as following both a literary and cinematic tradition of portraying doomed lovers. (As will be discussed, there is one scene in L'eclisse--that of the lovemaking of hands between Vittoria and Piero--that may be a specific allusion to Romeo and Juliet.) Mimi Avins writes of such cinematic doomed lovers in the Los Angeles Times (October 30, 1999):

Boy meets girl. Boy gets girl. Girl dies of incurable disease, vanishes in natural disaster, is unjustly accused and sentenced to death, decides not to ditch boring but decent hubby, whatever. As formulas go, the doomed love story has been a sturdy one. Although the frustrating reasons why the lover and the beloved cannot be together vary, the point is that we, the audience sniveling and wringing out our soggy hankies in the darkened movie theater, are supposed to celebrate the perfect love that cannot be. . . The candle of their love burned briefly. But while it flickered, oh, what a lovely light. Oh, what a load of romantic hogwash.

What makes L'eclisse stand apart from so many of the hackneyed other films of the doomed-lovers genre is the fact that Vittoria and Piero’s failure to love is largely unexplained. Or despite the title of L'eclisse and its reference to stars, Vittoria and Piero’s fault seems to lie perhaps within themselves. In the opening scene of the film which portrays the breakup of Vittoria and Riccardo, Vittoria explicitly denies that there is “somebody else,” a declaration nothing in the film contradicts. L'eclisse is among the rare films of Antonioni in which there is no adultery. And yet, infidelity might be considered to be the central theme of L'eclisse, an infidelity not of the garden variety, but of a stultifying, cosmic kind. (Billy Wilder once observed that a love story isn’t about what brings two people together but what keeps them apart.) Or an alternative interpretation of L’eclisse is that the film is not a tragedy: Vittoria and Piero are simply mismatched or mutually not interested in one another and decide to not see each other again. It happens every single day . . . and night.* My own problem with this interpretation is that it renders the film banal and this book worthless. Interpretations, like infectious agents, tend to breed other interpretations, and critics with differing views, like expert witnesses in courts of law, tend to cancel one another out. In the case of L’eclisse, this zero-sum game may be particularly appropriate, considering that neither Vittoria or Piero was present at the deserted intersection of Viale del Ciclismo and Viale della Tecnica at the end of the film, and no one will ever know what happened to two young lovers who had once planned but failed to skylark on a summer’s evening in Rome in early September, 1961. The Autumn Leaves will soon be blown chilly and cold, but, September, a September Song, yes, I’ll remember . . . a love once new has now grown old. Perhaps--after all is not said and not done--the explanation for the conclusion of L'eclisse is synonymous with the disappearance of Vittoria and Piero: the disappearance of an explanation. As in the very last sentence of Victor Hugo’s long tale of human misery:

La chose simplement d'elle-même arriva, comme la nuit se fait lorsque le jour s'en va.

[“The thing came to pass simply, of itself, as the night comes when the day is gone.”]

Vittoria and Piero are mismatched to the degree that they are literally apart for much of the film. It is not until over half the film has transpired that Vittoria and Piero even have their first conversation together (in the Bar della Borsa). There is a curious, episodic, ruptured quality to their relationship that is present from the inception of their meeting one another: we see them in a limited series of tableaux—such as their dates at the water barrel—as opposed to the continuous, streaming relationship that characterizes Claudia and Sandro’s traveling physically together in L’avventura, inhabiting the same time and space in a relatively seamless manner, especially in the latter half of the film. Unlike Claudia and Sandro who participate in a shared journey, Vittoria and Piero spend relatively little screen-time together in all of L’eclisse, a situation that lends a curious, detached quality to a film that seems to be struggling to be a love story, the narrative engine never finally cranking, igniting, and the tachometer revving in a forceful surge. (It is a sad day when one holds a “couple” such as Claudia and Sandro up as a healthier model of sustained regard than Vittoria and Piero.) The narrative structure of L'eclisse with its stuttering succession of disjointed vignettes depicting furtive encounters between Vittoria and Piero, mocks the plenitude and integrity of true love. Even when Vittoria and Piero are together they are apart, stuck in neutral in some deadend turnoff of approach and avoidance. Vittoria and Piero seem incapable of truly touching one other—lips and souls separated by a thin pane of glass—such that I am reminded of the intercourse of plants and their botanical dependence on the whimsy and caprice of wind and insects in the promotion of their lovemaking. In the end what Vittoria and Piero together have and have not is finally revealed for what it is and is not. Nothing.

Across the nearly 50 year trajectory of Antonioni’s films is the abiding concern with the failure of romantic love between a man and a woman. (As of this writing, Antonioni is said to have recently completed working on a portmanteau film together with Wong Kar-wai and Pedro Almodóvar, appropriately entitled Eros. The title of the segment which Antonioni has directed, Il filo pericoloso delle cose, is said to concern--not surprisingly--the end of a love affair [Il Nuovo-Spettacoli--Cinema. Internet Site. Retrieved 21 November 2001 from: <http://www.ilnuovo.it/nuovo/foglia/0,1007,89110,00.html>].)18 Of all of Antonioni’s major films, only Blow-Up and The Passenger are not “love stories”; nevertheless, even in these latter two films, there is female to whom the male protagonist becomes attached, an attachment which in short order leads to a hurried variety of dead end. In the three years between L’avventura and L'eclisse, Antonioni’s thematic moves--depending on one’s point of view--either a millimeter or light years: whereas L’avventura ends with the closeup shot of Claudia’s hand resting on the back of Sandro’s head as he sits weeping on a bench in a patio at the San Domenico Palace Hotel (with Etna as backdrop, replacing the church dome that had appeared in the opening scene of L’avventura), by the final shot of L'eclisse the two lovers are so utterly effaced that not even the parings of their fingernails remain.* In 1982, through the mouth of one of his characters, Antonioni expressly commented on his abiding penchant for filming love stories: Niccolò, the film’s main character, a movie director, is caught halfway à la 8½, in the conception of a new film. He knows that the film’s main character is a woman, but knows little else. (Antonioni will eventually make Niccolò’s film and call it “Identificazione di una donna.”) While Niccolò discusses his vague ideas regarding his film project with a associate, the associate remarks:

Una altra storia d’amore . . . Mi domando che senso ha al giorno di oggi una storia d’amore, una storia d’amore in questo sfacelo, in questa corruzione . . . (“One more love story . . . I wonder what’s the point of such a tale, one more story of love amidst this decay, this depravity . . .”).*

Like almost all of Antonioni’s male protagonists, Niccolò is a part of such depravity. Consider, for example, how he meets Mavi, his major love interest for the first half of the film, before she—as is typical for an Antonioni character—disappears: Niccolò’s sister is—of all the professions in the world—a gynecologist. While he is visiting his sister in her office, the phone rings. At his sister’s request, Niccolò answers the phone. He then begins a flirtatious conversation with a woman (Mavi) he presumably has never met and knows nothing about, a potential patient who is phoning to make a gynecology appointment. The sister then finally picks up the phone and jots down the woman’s name and telephone number to make the appointment. When the sister then turns her back, Niccolò furtively records the number. Before you know it he’s in the sack with the woman he had briefly spoken to on the phone who Niccolò then confirms has some type of gynecological problem, and who was told by Niccolò’s physician-sister not to have sex for a month. What a guy. Such men as Niccolò or Piero are more concerned about “catching feelings” than they are of contracting a sexually transmitted disease.

Such behavior is similar to that of the character, Corrado, played by the actor, Richard Harris, in Il deserto rosso. Corrado aggressively pursues Giuliana (played by Monica Vitti), the wife of his colleague and a woman who displays such overt psychopathology that a more normal man might wonder if it isn’t time to call the men in the white coats instead of Corrado’s decision to make love to a woman in a state of agitated delirium. All that Corrado seems to discern is that Giuliana is a good looking woman and that’s good enough for him.

Such behavior is reminiscent of Sandro of L'avventura, a man who tries to seduce his missing girlfriend’s best friend, Claudia, only hours after Anna has disappeared. Even Piero, not the most sensitive and empathetic of men, doesn’t display such behavior, at least between the two covers of L'eclisse. Piero does, however, first make love to Vittoria in his parent’s bed beneath photographs that are presumably of his parents, a choice that a psychoanalyst would have a field day with. (In The Story of Us [1999] a psychotherapist remarks that there are always six people in bed: the married couple as well as both sets of parents.) Vittoria pointedly asks Piero why he had not taken her to his own “pied-a-terre,” a question he admits he doesn’t know the answer to.

And then, there is Piero. From the moment when Piero first meets Vittoria in the Borsa, he is on the prowl, a male version of a dog perpetually—as opposed to cyclically—“in heat.” Piero desecrates the minute of silence—a prayer for the dead—by seizing the occasion to flirt with Vittoria. (Would Piero, a devout heterosexual, have engaged in such a conversation if a handsome man had stood on the other side of the stone column from him?) If Piero will disrespect the dead man, he will eventually disrespect the living woman. Piero pats a woman on the rear end in the Bar della Borsa in the presence of Vittoria when they first meet in a “social” setting. When Piero, in a very nasty manner, aborts his date with the Bestiola on the evening of the stock market crash, he impulsively gets in his Alfa Romeo and drives to Vittoria’s apartment to substitute one object for another. (How does Piero know where Vittoria lives?) This illness of serial womanizing is so grave chez Piero, that he appears to try to pick up the unidentified blonde who is exiting from Vittoria’s apartment building as Piero stands at the front gate of the building searching for Vittoria. Piero stares intently at the attractive blond woman (who not-so-accidentally resembles Vittoria, one good looking blonde just as good as another) who exits the front door of Vittoria’s apartment building, walks past Piero as he stands at the front gate, and then steps into her car. Indeed, Piero turns after the woman has passed him, continues to stare, and takes several steps in the direction of the blond woman as she enters her parked car before eventually driving off into the night. During their stroll in the Eur, Piero—again in Vittoria’s presence—ogles the nursemaid who is bending down to adjust her stocking. I do not know how many times in the course of human affairs, an engaged man (or woman) has sat at the dinner table of his fiancée and her family and secretly fondled or played footsies beneath the table with the sister of the woman he was about to marry. Such an act is in Piero’s repertoire. (Antonioni has not shown an interest in a single film he has ever made in the theme of the grand disparity between human vice and virtue; instead, he is primarily interested in a very narrow spectrum of human pathology.)

I do not believe that Antonioni’s portraits of such men are drawn primarily to incite repugnance in the viewer, no matter how repugnant the behavior may be. Instead, these “love stories,” concern more primitive drives than those usually associated with some more rosy view of romantic love. As Antonioni himself has said in a statement distributed at Cannes when L’avventura was presented (quoted by Leprohon, pp. 90-92 of his book, Michelangelo Antonioni, an Introduction): “Eros is sick. . . . the catastrophe is an erotic impulse of this order: cheap, useless, unfortunate.”

Apposite of this statement by Antonioni--one with a Freudian resonance--Chatman quotes Freud’s “The Most Prevalent Form of Degradation in Erotic Life”:

“When the original object of an instinctual desire becomes lost in consequence of repression, it is often replaced by an endless series of substitute-objects, none of which ever give full satisfaction. This may explain the lack of stability in object-choice, the ‘craving for stimulus,’ which is so often a feature of the love of adults.”

John Simon in his essay on L’avventura has noted that approximately two centuries before Freud, the French moralist, Chamfort, wrote, “Love, as it exists in our society, is only the exchange of two fantasies and the contact of two outermost layers of skin.” (an adage also cited by the character Geneviève in Renoir’s The Rules of the Game / La Règle du jeu: “L'amour tel qu'il existe dans la société, n'est que l'échange de deux fantaisies et le contact de deux épidermes.”) Or there is the informed observation made by an older physician in the 1957 Russian film, The Cranes are Flying (Letyat zhuravli), that “Love is a benign and temporary mental illness.”

Sandro and Piero and Niccolò lost something long ago and have been looking for it ever since. Claudia and Vittoria and Mavi are not the lost object. The men just keep-on-keeping-on looking for love in all the wrong places. (Alcohol and drugs play little if any significant role in the majority of Antonioni’s films; his characters suffer from other afflictions. Substance abuse as a theme does not lend itself to the expression of Antonioni’s world view. Yes, a drunken man drowns in L’eclisse but this has little to do with a cinematic exploration of the ravages of alcoholism. People get high in Blow-Up but the issue is not focused on marijuana but rather on alteration of consciousness and distortion of perception.)

Antonioni’s genius does not lie in his choice of topics or of themes. Writing of L’avventura in La Nouvelle Revue Française (November 1960; reprinted in Leprohon, Michelangelo Antonioni), Dominque Fernandez has written:

We have Antonioni’s universe set up and in position. It resembles--this, we must admit--those of all the great modern creative artists. On the subject of the unsuccessful artist, on the impossible couple, on the vanity of life’s quest, on the inevitability of solitude--on none of these is Antonioni really original.

Specifically, Antonioni isn’t the only major Italian filmmaker concerned with men chasing women. Compulsive womanizing appears time and again as a major concern of Fellini. An obvious example among Fellini’s films concerns Marcello’s pursuit of Gaea-Tellus in La dolce vita, embodied in the seemingly polar extremes of the Anita Ekberg character and Paola, l’umbra, the young girl from Umbria. Casanova and Città delle donne are but two other obvious examples. Perhaps the most strident example of Man’s neediness for Woman occurs in Amarcord with the image of Theo, the institutionalized schizophrenic uncle, stuck in a tree incessantly screaming the plaintive mantra, “Voglio una donna!” / “I want a woman!” (One can imagine either Sandro or Piero suffering a psychotic break and climbing into such a tree, singing such a song.) More recently Giuseppe Tornatore’s Malena portrays a world of young boys or childlike men lusting after the idealized Woman. It is not just men who are depraved, but as Antonioni has noted, Eros who is sick. Thus, some of Antonioni’s female characters--most notably the psychotic nymphomaniac who assaults Giovanni in La notte--have an extremely disturbed sexuality. (Giovanni actually seems indecisive as to whether he should accept the advances of such an ill woman?!)

Pietro Germi directed Divorzio all’Italiana at the same time that L'eclisse was made in 1961. Although the Germi film is ostensibly a farcical, comic satire, the fundamental issue of Love, capital L, is--as in the case of most of Antonioni’s film--the heart of the matter. In Divorce Italian Style, all of the males of Agrimonte--a provincial, Sicilian town that serves as a stand-in for the universe--are frenetically searching for some idealized amalgam of love and sex. The Marcello Mastroianni character in the film--unhappily married to a woman whom he admits in explicit voice-over that he married because of her large, round rear end--is now ten years into his marriage and dreams only of his nubile, teenage cousin played by Stefania Sandrelli. In one scene while husband and wife lie side by side in bed during the scalding heat of an afternoon siesta in Sicily, the wife with the attractive bum turns toward the Mastroianni character and presents a little soliloquy on love:

Sai che pensavo? Mi chiedevo, ma noi, chissà perché viviamo? Ma, tu mai c’hai pensato quale è lo scopo vero della nostra vita? È amore. È amore. Noi viviamo per amore. Se non si amasse, come tanti fiori in autunno . . .

(Do you know what I was thinking? I was asking myself, why are we alive? Haven’t you ever asked yourself what is the real reason why we live? It is because of love. Love. We live to love. And if this were not the case, then like so many leaves in autumn . . .)

Such a world view could be written on a small piece of paper contained within a bon bon read by a mannequin named Joy.

The Mastroianni character, an adult male who dreams only of an adolescent, new love with his cousin, is annoyed by the discourse. His only response is to correct his wife’s lapse in the use of the imperfect subjunctive tense in Italian, the effect being that the wife’s declaration is at once profound, inadvertently ironic, and trivialized. At such a moment, Germi and Antonioni become kindred spirits.

Although Fellini, Tornatore, Germi, and Antonioni may at times be obsessed with a similar theme, they are very different directors. It is not choice of theme or subject matter that distinguishes them from one another, but factors largely concerned with style, point of view, attitude, tone, goals, seriousness of purpose, execution, the manner in which the artist chooses to approach an audience, and perhaps, finally, a nagging, subconscious, ever present doubt concerning the vanitas vanitatum . . . the utter worthlessness of it all. It is the peculiarities of these latter factors that make Antonioni so unique.*

In not a single film by Antonioni is there such a thing as a happy couple. One might also add that in not a single film by Antonioni is there such as thing as an unambiguously happy person. Although almost every film Antonioni has ever made has been a “love story,” how many times has a single character in his films ever uttered, breathlessly, in a heartfelt manner, the three words, “I love you”? Claudia, of L’avventura, may start out happy, but she ends up contaminated by her contact with Sandro, a kind of venereal disease of spiritual as opposed to microbial dimension. The Girl without a name in The Passenger may seem more happy and a freer spirit than most of Antonioni’s characters, but her taste in men is suspect, and if she is indeed an enemy agent, then she is thoroughly pestilent.19

In Antonioni’s films there is generally an aimless, robotic, and driven quality to the sex scenes, as if there were physical engagement--if that--without any real amorous commitment. (Think of the “orgy” in the wharf shack in Il deserto rosso or the lovemaking between the Sarah Miles character and her lover witnessed by the Photographer in Blow-Up.) We may speak of Antonioni making nothing but love stories, but there is very little, if any, love in any of his films. And in spite of an increasing number of ever more explicit sexual scenes in Antonioni’s later films, the sex seems mechanical, perhaps even pornographic in its lack of any real lyricism. (Even as pornography such sex scenes would seem to fail if they do not achieve titillation.) Antonioni’s films may be viewed as disturbingly unromantic or “anti-romantic,” films concerned neither with heartfelt love or sex, but instead, the failure to achieve any consummation of either. Eros may be sick, but whose God is infirm: Antonioni’s, his character’s, ours? Brief Encounter may sometimes be criticised as overly chaste and sexually inhibited, but there is more love and true physical engagement between Laura and Alec in their kissing and handholding than any couple Antonioni ever projected on the screen.

Although one might conclude that Antonioni is telling us that true love doesn’t exist, this would be a hazardous conclusion. ([Caution: Plot Spoiler] In La dolce vita Fellini seems to offer us the chance to jump at this conclusion even more so than Antonioni: Steiner, a parody of a happy husband and father--a man so cultured and refined that he reads a Sanskrit grammar and plays Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor on the organ--is in reality a murderer who kills his own children and himself. Agnès Varda similarly explodes the picture of an idyllic marriage in Le bonheur.) If all of Antonioni’s characters are unlucky in love, this does not mean that outside the frame of his movies true love does not exist, nor that Antonioni himself has not established a successful and loving marriage. (His relationship with his present wife, Enrica Fico Antonioni, is an enduring one that has lasted over 25 years, in sickness and in health). By all accounts, Antonioni is a scrupulously honest and rational man. I cannot imagine that he would deny the obvious, that happy and loving couples exist. Nowell-Smith quotes Antonioni as once saying, “I believe in happiness: every time anyone asks me about this, I insist on saying that it exists. But I don’t believe it is lasting.” (Nowell-Smith. L’avventura. page 57.) After examining Antonioni`s films, an accurate conclusion would be--not that love doesn’t exist--but that Antonioni is interested in making films about unhappy couples.*

In the final shots of both Vittoria and Piero--while she is standing in the street outside Piero’s office while he sits inside the office enveloped in the symphony of ringing telephones--a small, enigmatic smile appears on both their lips.* Only minutes before, both Vittoria and Piero had seemed so happy, entwined in each other’s arms on the couch, playing with one another on the floor. Their final words to each other are a declaration of eternal love. The question arises as to why when all seems so well, Antonioni does not show this couple embracing at film’s end. Antonioni denies us the ostensibly happy ending, a denial that approaches near universality in Great Art. (Piero eliminates women, Antonioni kills his picture, and everyone—Vittoria included, inhabit an enlightened world where women are achieving parity with men in every sense, good and bad—and conform to Oscar Wilde’s observation already referenced in Endnote #18 that “each man kills the thing he loves.”) One possible explanation among many that might explain the enigmatic behavior of Vittoria and Piero (as opposed to the behavior of the film director, Antonioni) is that this couple may have a common, profound, and largely subconscious desire to quit while they are ahead. Cash in your chips and run.

All or nothing at all.

If it's love, there is no in between.

Why begin to cry, for something that might have been.

No, I'd rather have all . . . or nothing at all.(music, A. Altman; lyrics, J. Lawrence)

Frank Sinatra sings “All or Nothing at All” at youtube.com: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MORpiGvsaNA&feature=related>

But Eros is insatiable and even all is still nothing at all. If one wants to express this conceit in a little more fancy manner, one may consider what Barbara Socor has written in a Lacanian vein in “Celluloid Couches, Cinematic Clients,” that “Human desire cannot be slaked, and satisfaction is inimical to it.” Such a view suggests that by separating at the apogee of their relationship, Vittoria and Piero thus avoid the inevitable deception of consummation. They avoid becoming Vittoria and Riccardo, the mistake that L'eclisse opens with. Reading Lacan on such a subject is like diving into a swimming pool filled not with water, but molasses; trying to sort out the Lacanian domains of The Real, The Imaginary, and The Symbolic, and their relationship to the absent maternal phallus seems unnecessarily complicated compared to the common lay belief that marriage is a trap. But to give Lacan, the devil, his due, one might say that while Antonioni is merely an empiricist whose grand observation is that love is impossible, Lacan tries to specifically explain why this is the case. The universal paradox, the impossible “double-bind,” is that for Vittoria and Piero--or any couple for that matter--to possess one another, they must break apart. This is a conclusion not far from the trendy, relatively newborn psychology of “attachment theory,” or the concept of “approach-avoidance behavior” that pertains to the issue as to why Vittoria and Piero may never keep their 8 pm appointment. One more sophisticated psychological explanation among many that says: “If I can have her, I don’t want her; but if she doesn’t want me, I crave her.” In social psychology the arguments, terminology, and theoretical elaboration that exist to elucidate such a declaration are stultifying. There isn’t merely “approach-avoidance” phenomena,” but “approach-approach, avoidance-avoidance, and double approach-avoidance behavior,” all outlined in an academic literature so arid as to make one think that Borges’s Library of Babel must be located in the Sahara, or, better yet, in that other desert where David Locke also got stuck, the badlands of Tabernas, Almería. After approaching and reading the literature on approach-avoidance behavior, I end up—like all of Antonioni’s creatures—just wanting to run away and avoid it all. (Or as Napoleon once remarked, “En amour, la seule victoire, c’est la fuite” / “The only victory in love is to flee”; a quotation specifically uttered by the character played by Charles Boyer in Max Ophüls masterpiece of doomed love, The Earrings of Madame de . . . [1953]. ) This is the dynamic also explicitly at play in Wharton’s The Age of Innocence when the novel’s character, Ellen (played by Michelle Pfeiffer in the Scorsese film adaptation of the book), in her youth exclaims to her would-be love-of-her-life, Newland (played by Daniel Day-Lewis in the movie): “Can’t you see? I can’t love you unless I give you up!” (Caution: Plot Spoiler) The cruel symmetry is such that at novel’s end when Newland is an older widower and “free,” it is now he who rejects one of life’s rare second chances at reclaiming lost love and, instead, embraces Ellen’s exclamation of many years before: I can’t love you unless I give you up . . . again! This sentiment is not far removed from Romeo’s declaration to Juliet, “I must be gone and live, or stay and die” (Act 3, Scene 5). Likewise, in the film, Vertigo—an ostensible tale of reincarnation—the James Stewart character’s second chance with the Kim Novak character is doomed. The Novak character exclaims to the Stewart character before her “first” death: “And if you lose me, then you’ll know I loved you and wanted to go on loving you.” In The Passenger David Locke will also lose his second life and die twice. In L'eclisse what finally may be occurring is an existential self-abnegation mutually sought by two would-be lovers. The world of L'elisse in 1961 is one of insane nuclear proliferation—the capacity to destroy the world many times over with a surplus of atomic bombs—and mutual assured destruction (“MAD”). Vittoria and Piero’s no-show at the conclusion of the film may be seen as a refusal to live in a world determined to die. Or more frightening yet—this desire to die—may be independent of 1961 and the possibility of nuclear war: a primordial desire to cease to exist on the part of human beings, referred to by Freud by the Greek word, “Thanatos,” or “death instinct.” The ultimate form of self-abnegation, suicide, occurs remarkably at both the beginning and end of The Passenger, a disappearing act of tragic import. The first suicide is when David Locke abolishes himself and assumes the life of David Robertson. The second suicide occurs when he lies down in the Hotel de la Gloria yielding his life to the Angel of Death just outside his window. Although Freud emphasized the fundamental conflict between Thanatos and Eros, in both The Passenger and L'eclisse the issues at hand may not be those of a primal conflict between Life and Death, or the Girl being a truly foreign agent stalking David Locke with scythe and hourglass in hand, or the inability of Vittoria and Piero to fulfill a Platonic parable of love blending two natures into the white and yolk of the single shell, but a struggle to the death of death grappling with death, death the inevitable victor in a creation doomed from its inception.

All that may remain for some ex-lovers—the enlightened and conscious few—is the memory of a summer day’s fantasy of imagined fulfillment. Some such lovers--perhaps both Vittoria and Piero with their small smile on their faces in their last scenes in L'eclisse--may even in the present be anticipating the future enjoyment of such a memory.*