IV. METEMPSYCHOSIS

He faced about and, standing between the awnings, held out his right hand at arm’s length towards the sun. Wanted to try that often. Yes: completely. The tip of his little finger blotted out the sun’s disk. Must be the focus where the rays cross. If I had black glasses. Interesting. There was a lot of talk about those sunspots when we were in Lombard street west. Looking up from the back garden. Terrific explosions they are. There will be a total eclipse this year: autumn some time.

James Joyce. Ulysses. The corrected text. (8.569)

A mask tells us more than a face.

Oscar Wilde.

(A total eclipse of the Sun did occur on 9 September 1904 at 20:44, lasting 6 minutes and 20 seconds, just about the date (late summer, not autumn) when Vittoria and Piero were to meet--perhaps, in fact, the exact date of their last appointed rendezvous-- just about the same time in the evening, just about the length of the coda. Molly and Leopold, lying in bed in opposite directions, 180° apart. Vittoria and Piero.)

Not only is there a kind of transmogrification between objects and beings, but there also appears to be a fluidity, a loss of boundaries, or confusion between different people. Even the line between where the actress Monica Vitti’s name ends and Vittoria’s name begins is confluent.

We do not even know whose voice truly issues forth from the mouth of Piero. The character Piero is himself an amalgam of a visual representation of the actor, Alain Delon, and the disembodied voice of an uncredited native Italian speaker who provides the auditory representation of Piero, an act of dubbing Delon’s accented Italian in post-production of L'eclisse. Delon’s voice in the original Italian soundtrack of L'eclisse was in fact dubbed by the Italian actor, Gabriele Antonini, a photograph—a “pure” visual image—of whom is on page 28 of Vol. 3, Part 1, of the Dizionario del cinema italiano. When Vittoria and Piero recite their lines of eternal fidelity to one another in Piero’s office, it was actually Gabriele Antonini who was speaking into a microphone in the dubbing stage of the post-production facility.

His Master's Voice (La voce del padrone)

Gabriele Antonini: Piero's voice

If you wish to hear snippets of Delon actually speaking Italian see (viz. “listen to”) the horrible American film, Once a Thief [1965]. In this latter film Delon plays an Italian immigrant to America from Trieste whose accented English is disconcertingly French and whose brief Italian dialogue is not the perfectly unaccented Italian of Piero in L'eclisse. Or listen to and watch a brief video clip of Delon attempting to adopt a southern Italian accent in his performance in The Yellow Rolls-Royce [1964]; (vide infra, blue hyperlink towards the conclusion of Endnote 29 of this book). An uncredited Italian actor, Achille Millo, had dubbed Delon’s Italian dialogue for Rocco e i suoi fratelli (in which Delon played an Italian from Lucania) made shortly before L'eclisse in 1960. In the case of the Sicilian prince, Tancredi Falconieri, who Delon played in Il gattopardo [1963] shortly after L'eclisse, Delon’s Italian was dubbed by Carlo Sabatini, again an uncredited attribution. We will never know the “pure” Piero (at least in the present Criterion Collection version of L'eclisse which contains only the original Italian sountrack), but only his visual and auditory mosaic. I am in personal possession of a Pioneer Ldc., Inc. (Japanese) DVD of L’éclipse (“Cinemadict Coollection” [sic]) in which the audio is curiously, only in French with optional Japanese or Chinese subtitles; it is my estimation that the audio of both the actors Vitti and Delon is spoken in French by themselves based on the degree to which I recognize the distinctive voices of both actors, particularly Vitti, and their manner of speaking French. (I am not a good lip-reader, but it appeared to me that at times Delon was mouthing from a visual analysis some dialogue in French.) It is also theoretically possible that in some countries the voice of Delon-Piero in L’eclisse was dubbed into languages other than Italian or French, i.e. English or Greek; I have personally not seen (“heard”) such versions of L’eclisse, which does not mean that they do not exist. A cursory Internet search reveals that “Film Prestige” produces a box-set version of several of Antonioni’s films including L’eclisse (“Zatmenie”) that offers the option of Russian audio. As already noted in Chapter 3, Antonioni had first met an actress whose native tongue is Italian, Monica Vitti, when he hired Vitti to dub Dorian Gray’s dialogue in Il Grido [1957]. Curiously, “Dorian Gray” is the stage name for Maria Luisa Mangini, a native Italian speaker. I can only speculate that Antonioni may have wished to dub Mangini’s Italian because it was accented, Mangini having been born in the extreme north of Italy in Bolzano, the accent of which bears a German flavor. Likewise, the early films of Claudia Cardinale had her Italian dubbed by other Italian actresses, presumably because this actress of Sicilian heritage who was born in Tunisia had an “unsuitable” regional accent with a French tinge. Like Delon, Cardinale’s Italian in Il gattopardo was dubbed; in the case of Cardinale, by an uncredited Italian actress, Solvejg d’Assunta. In some cases of dubbing—without access to further particulars—it may be impossible to know why one native Italian speaker’s voice was substituted for another (e.g., why Alberto Sordi dubbed Marcello Mastroianni’s voice in the 1950 film Domenica d'Agosto.) Jean Renoir briefly discussed the issue of dubbing in his 1961 French television interview with Jacques Rivette:

Most talking pictures are simply silent films where the [inter]titles have been replaced by some sounds coming from a mouth. It’s clear that certain people accept dubbing. If we accept dubbing, we accept that the dialogue isn’t real. It’s a refusal to believe in the mysterious connection between the intonation of a voice and its expression. We cease to believe in the unity of the individual.

“Jean Renoir parle de son art” (Portions of the interview are available on YouTube [ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LKCrOLcDbjE ] , retrieved 2 March 2009, as well as The Criterion Collection DVD of Renoir’s The Golden Coach).

This is but one more reminder that movies—like the fickle declarations of eternal fidelity of Vittoria and Piero—are both more or less something other than truth itself . . . and that film criticism may, thus, abet or debunk a lie. In one possible scenario of so-called film theory, the best films would not exist and hence neither would the film criticism thereof.

In one of the most striking, digressive and hysterical scenes in L'eclisse, Vittoria transforms herself into an African woman.

Anyone but me, anywhere but here

The issues of masquerade and disguise appear repeatedly throughout Antonioni’s films, phenomena related to so-called “shapeshifting.” In Antonioni’s early documentary Nettezza urbana (1948), a man who is picking through garbage finds a black mask and dons it. The English episode of I vinti contains one of the few attempts at conventional comedy in all of Antonioni’s films. The episode begins with a kind of running gag in which the reporter for The Daily Witness, Ken Wotten, is repeatedly mistaken for someone else by the newspaper’s telephone operator, Miss Davis. Apparently to soften the downbeat, disturbing conclusion to the episode in which Aubrey Hallan is convicted of murdering a prostitute, Antonioni chooses to end the episode as it began: Wotten outside the courtroom on the telephone being mistaken for someone else by Miss Davis, “Londonderry Air” (“Danny Boy”) being played in a minor key in the background. In La signora senza camelie, the main character is an actress whose profession concerns the imitation of other characters (in particular, Joan of Arc). In L’avventura Claudia exchanges the shirt off her back with Anna, experiments with the wearing of a dark wig, adopts Anna’s lover, and seamlessly slips into the shoes of Anna’s existence. Blow-Up begins with the scene of the Photographer disguised as a homeless bum as he exits a London doss house. In The Passenger David Locke exchanges his life for David Robertson’s. These attempts to become another person resonate with the allied Antonionian theme of flight and the desire to escape to other lands (a desire shared by the slackers of Fellini’s I Vitelloni, who dream of escape to Africa, an endless fantasy that still haunts contemporary Italian cinema in such recent films as L’ultimo bacio). There is also a resonance with the general care and concern Antonioni shows to the costumes and dressing of his characters, as well as with Antonioni’s preoccupation with mannequins--both living and not--in Cronaca di un amore, Le amiche, Blow-Up, Zabriskie Point, and Identificazione di una donna (as already discussed in more detail in Chapter 2).

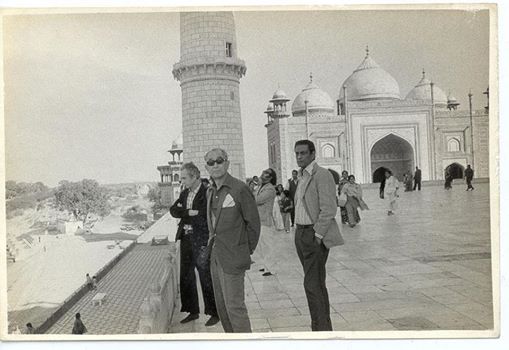

There is a remarkable resemblance between a series of consecutive, critical scenes in Aparajito (1956), the second chapter of Satyajit Ray’s—to use Pauline Kael’s adjective, “luminous” Apu Trilogy—and L'eclisse. (There is little doubt that Antonioni was familiar with Ray; Aparajito won the Golden Lion at the 1957 Venice Film Festival. Indeed, Antonioni, Ray, and no less than Akira Kurosawa were once together in India.)

Antonioni, Kurosawa, Ray at the Taj Mahal

January 1977

(For more on Satyajit Ray and this encounter see: http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3038-flashback-satyajit-ray )

Midway through Aparajito, the young boy, Apu—against against all odds—gains admittance to a humble, private school in rural Bengal. Apu shows remarkable aptitude and is rewarded by the headmaster who lends Apu a series of old textbooks that are turning into dust. A flurry of brief scenes ensues which shows the exultation of Apu as he learns of a world beyond that of the impoverished village that is his universe, a universe that is little more advanced than that of the Iron Age. There is a tender scene in which Apu excitedly explains to his proud, widowed mother his “discovery” culled from an old textbook of how the moon orbits around the earth which in turn spirals about the Sun, and how the conjunction of heavenly bodies may produce an eclipse. This scene is followed by another scene the following day when Apu’s mother searches in the village for her young, only child. Suddenly, Apu startlingly appears from behind a door completely dressed in the comically slapdash garb of a black African warrior resplendent with makeshift shield and spear and dramatic facepaint. Apu then dances in a Bengali field, shouting repetitively with childhood glee, “Africa, Africa, Africa!” This scene is followed by a nighttime scene of the little Bengali boy who would be an African king, lying on the dirt floor of his impoverished room, surrounded by his precious books--among which must be a geography--driven by exhaustion to sleep. Ray in a volley of ever increasing close-ups and dissolves finally focuses his camera on the bright, white flame of the small lamp which illuminates the hut, a light little different from that of the conclusion of L'eclisse.

Vittoria is a sophisticated, Western European woman who masquerades as an African. Apu is a young boy from the most impoverished of hovels in Bengal. And yet Apu, like Vittoria, dreams of a world other than his own.

Escape — it is the Basket

In which the Heart is caught

When down some awful Battlement

The rest of Life is dropt —

Emily Dickinson

In L'eclisse people and things are often doubled or transform one into the other (metempsychosis!). Pointed references, for example, link Riccardo and Piero. This was touched upon earlier in the “man as chair” image. Riccardo suffers a further reincarnation when Piero--like Riccardo before him--comes uninvited in the middle of the night seeking out Vittoria at her apartment. An especially convoluted reference occurs at the beginning of the second sequence in the Borsa. Ercoli, Piero’s boss, remarks how hot the weather is and, abracadabra, Piero proudly whisks out of his breast pocket a small, hand-held, portable fan which Piero then offers to give to his boss. This harks back to the conspicuous fan in Riccardo’s apartment. Ercoli then makes a significant and somewhat gratuitous, curious comparison, suggesting to Piero that the small fan looks like an electric razor, recommending to Piero that he instead should give the fan to Dino, another employee in Piero’s office; later in the same scene we briefly see Dino passing breezily before us with the fan, having taken possession of it in an apparent ellipse. (Who will Dino subsequently give the fan to?) Thus, Antonioni does not leave the reference between the fan of Riccardo’s apartment and the hand-held fan of Piero rhetorically bonded in a simple, linear correspondence, but instead does a kind of baroque, rhetorical and allusory twining by additionally reminding us that the little fan is also like an electric razor, taking us back once again to Riccardo’s apartment where Riccardo had earlier been shaving with such a razor. Furthermore, like so many things in L'eclisse, the fan has become smaller, things have shrunken, objects resemble elements with a short half-life, behaving like volatile molecules that exist in an unstable state. The fan has achieved the quality of a metaphysical hot potato, unable to persist in one form or in one person’s possession for long. Covalent bonds between particles--or people--are tenuous, particles and beings acting like sub-atomic bits of matter whose existence and mating is so fleeting that a lifespan or a love affair is measured not in the grace of years but in the fleeting evanescence of relative nanoseconds.

A particularly important linkage between Riccardo and Piero, one that is typical of Antonioni in being both simultaneously substantial and inconsequential, concerns the ashtray broken by Riccardo in the opening scene of L'eclisse and Piero’s discarded matchbook thrown in the water barrel much later in the film.* Their common ground establishing the linkage between the two men is both obvious and subtle. Both the ashtray and cigarette matches concern smoking, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Both objects are either cast off or broken by the men. In Riccardo’s case, he “accidentally” breaks the ashtray. In Piero’s case, he discards the matchbook as garbage in the water barrel. Importantly, however, both the ashtray and matches are part of Vittoria’s “canvas.” As we have already seen, the ashtray is part of her composition in the picture frame of the opening scene. Her other work in progress done in a different medium is the surface of water in the barrel, where Piero’s matchbook becomes part of the picture. What to Riccardo and Piero is detritus, is to Vittoria the fundamental building blocks of a universal table of elements, the unformed clay of art, things.

When Vittoria leaves Marta’s apartment to search for the missing dog (evasion, flight escape!), she finds the black poodle who is now walking on hind paws resembling a little human being. Vittoria asks two of the dogs if there are any problems between them (“Ci sono problemi fra di voi?”), completing their anthropomorphization.*

Are there any problems between you two?

The God Zeus (also the name of Marta’s dog) , was fond of visiting the earth disguised as someone else, an avatar. Did Antonioni consider naming the dog Proteus, and reject this as too obvious? According to Marta, men do not merely resemble animals; instead, she employs the third person plural of the verb “to be” when she announces that “Blacks are monkeys.”* According to Arrowsmith (p. 67; p. 80; p.180, note 1) the ancient center of the Borsa was the Parco Buoi, or oxen pen--where, like the island of Circe, Aeaea--men are turned into beasts.* (The Borsa also is fronted by the Piazza di Pietra, a Medusa-like world of stone.) There are several other deliberate examples of metamorphosis such as the blurring of identity regarding the Bestiola--a woman once blond, now brunette--somehow confused with Vittoria, who also had recently transformed herself briefly into a “brunette” in Marta’s apartment. The Bestiola is, of course, a beast. She awaits Piero outside a storefront with a lacework, metal grill, immediately below Piero’s office on Via Po near its intersection with Via Salaria--opposite the Villa Giorgina with the tall pines that Vittoria will gaze upward upon in her final shot--the “solito posto” where we last see Vittoria after her final meeting with Piero in his office.*

Vittoria will stand where you are someday.

In this final encounter with Piero in his office Vittoria is also transformed into a beast, a tigress who claws playfully at Piero as they frolic on the floor. (Brunette also reminds us that in Il deserto rosso, “[Giuliana] throughout [the film] makes various animal noises, as she does near the end, when she is in the lobby of Corrado’s hotel.” [p. 102].) These subtle (or not so subtle) linkages between the Bestiola and Vittoria conform to Piero’s degree of fidelity towards objects and women. Piero is able to discard his Giulietta for a BMW as easily as he is able to supplant the Bestiola with Vittoria.

Throughout Antonioni’s films the motif of doubles relates also to the allied theme of the interchangeability of one person with another. Piero is easily able to supplant one woman with another--Vittoria for the Bestiola--because the precise object of his desire is less important than the narcissistic origin of the desire. Such a need is temporally satisfied by the proximity of any marginally acceptable warm body. Piero’s cousin, Sandro of L’avventura, is remarkably able to switch from Anna to Claudia in the blink of a cinematic eye. For men such as Piero and Sandro, the primary criteria for chasing a woman do not depend on how deep is her soul and how tender is her touch but on whether she can fog a mirror with her breath. (For the James Stewart character in Vertigo—a tormented man accused by some critics of engaging in a kind of metaphorical necrophilia—even the latter criterion may not be necessary.) Writing of L’avventura, George Amberg notes that “. . . every person in this particular social setting is expendable. One protagonist can be substituted for another, like an under-study taking over the leading role without disturbing the balance of the cast.” The very center of Le amiche lies only millimeters away from the empty heart of L’avventura. In many ways Le amiche is--depending on one’s choice of metaphor--either a dry run or dress rehearsal for L’avventura. Both films concern a kind of romantic musical chairs, the old Antonionian issue of who belongs to whom. The beach merry-go-round, a Ronde à la Ophüls of one lover bouncing back and forth with another. As in L’avventura, attempted coupling is everywhere: on three occasions in Le amiche, Antonioni risks committing a tautology when he repetitively thrusts pairs of strangers who are smooching into his frame: once, a couple necking on the beach; twice, a couple embracing in the hallway outside the room of Lorenzo and Rosetta’s tryst; thrice, a servant and her boyfriend kissing on the street outside Momina’s living room (where only seconds earlier Momina had been kissing Carlo). Couples are everywhere. Love--as in a Gershwin tune--is in the air--but deception and loss, as in an Antonionian refrain, are just around the corner. Likewise, Niccolò of Identificazione di una donna can exchange Mavi for Ida without missing a beat. Such fickleness is central to the conflict of Italian gallismo or the syndrome of Don Juan in general. Questa o quella per me pari sono . . . . s’ oggi questa mi torna gradita, forse un’ altra doman lo sarà (“This girl or that girl are the same to me. . . . If today I find this one pleasing, some other morrow I may find another pleasing.” The Duke of Mantua’s aria from Verdi’s Rigoletto, Act I, Scene I ). As in the Italian proverb, “chiodo scaccia chiodo” (“One nail drives out another”), or in the American idiom, “ricochet romance,” one new woman replaces the old. From a female perspective, Molly Bloom touches upon a similar phenomenon when at the very end of Ulysses she thinks of which color flower to wear in her hair or which man to inhabit her life, “. . . and I thought well as well him as another . . . .” “La donna è mobile” (Rigoletto, Act III). The irony, however, in Verdi’s opera is that while men sing of the fickleness and inconstancy of women, men are themselves “mobile” (fickle and inconstant). Vittoria replaces Riccardo with Piero. Piero replaces the Bestiola with Vittoria. Who will Vittoria and Piero replace each other with?

From Antonioni’s first feature film, Cronaca di un amore, Antonioni expresses his fondness for inviting his audience to confuse one character with another. In this latter film, there is an indoor scene in which Paola first broaches the subject of killing her husband to her lover, Guido. The scene is immediately followed by an outdoor shot of a commercial street in Milano in which a young couple are seen walking on the sidewalk towards the foreground. From a distance, the couple strongly resembles Paola and Guido, not only because of their physical characteristics but because the preceding scene would also imply that this couple would be the same hero and heroine of the film. Antonioni’s camera follows the couple as they approach us until we discover that the couple are complete strangers. Hitchcock invites a similar trap for both the James Stewart character and we the audience when in Vertigo we are momentarily uncertain who is the blond woman seated in Ernie’s restaurant in San Francisco: is the woman the supposedly dead Madeleine, or someone else? In fact, Hitchcock repeats this “trick” several times in the second half of Vertigo, so much so that we “see” that the James Stewart character “sees” Madeleine, his lost love, everywhere he looks.

In L'eclisse, after the abortive meeting between Piero and the Bestiola, when Piero goes to Vittoria’s apartment, we see a young, blond woman exiting from the front door of the building as she walks in the direction of Piero. Antonioni invites us to assume that it is Vittoria, who it is not. There is a particularly striking shot present in the original print of L'eclisse--but edited out in some later versions of the film--of a young blond woman in the Eur in the coda of the film. We first see the woman filmed from behind and we have every reason to believe that it is Vittoria. As the woman eventually turns and we see her face gazing in our direction, we realize that that the woman is not Vittoria but an uncanny double who is deciving the fourth wall of cinema and staring at us briefly in the eyes, Antonioni, his blonde, lovely hair blowing in the wind, taunting us. It would be fitting, however, if this blond woman in the coda of L'eclisse was also the blond woman we had seen early in the film exiting from Vittoria’s apartment, comprising, thus, a case of recurrent mistaken identification concerning the same person. Indeed, throughout the coda of L'eclisse we serially repeat a similar error, believing that other pedestrians are perhaps Vittoria and Piero when they are not. Such a ruse on Antonioni’s part is particularly powerful at the end of L'eclisse when we truly expect to see Vittoria and Piero at their 20.00 rendezvous. Our entirely reasonable, visual search for the couple leads us not to the hallucination of a desired object--a kind of mirage--but more precisely to an illusion or distortion of a true percept. The blond woman of the coda is truly there, but she is not who we initially believe her to be, Vittoria. As is so often the case with both Antonioni and Hitchcock, we—our very perception—is being manipulated by the artist. The film, L'eclisse, may be seen as a sublime manipulation in which at the end of the film—when Vittoria and Piero both deceive and manipulate one another by concealing their true feelings and reciprocallly standing each other up—the film finally reveals itself as an elaborate hoax in which we the audience have been deceived and manipulated as well.

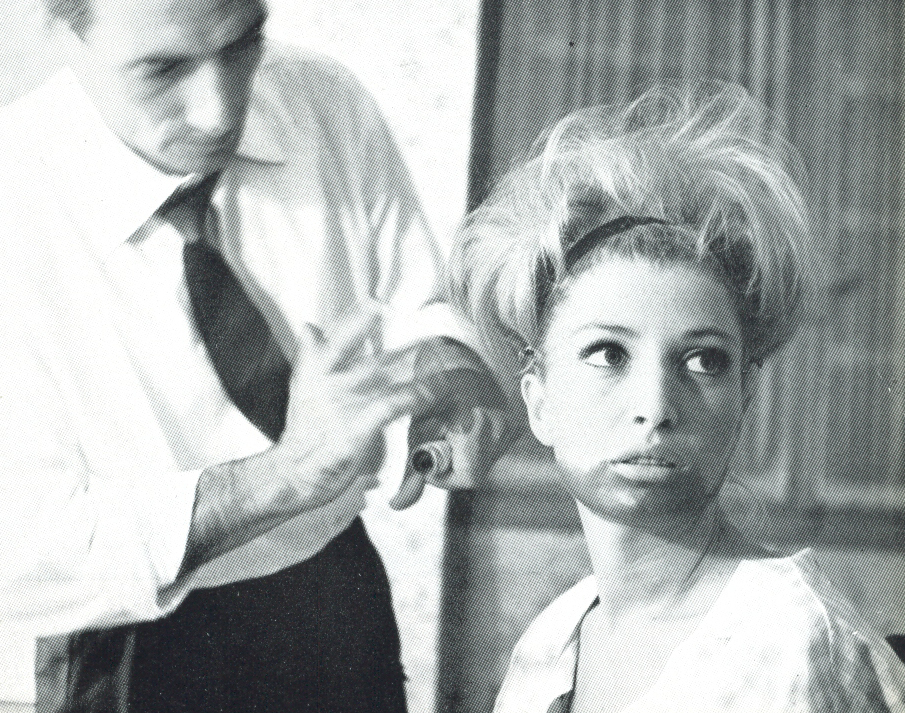

Characters may molt into other beings before our very eyes. Vittoria does so when she transforms herself into an African woman. (Photograph from Lane, John Francis. [Editor]. L'eclisse di Michelangelo Antonioni. Key makeup artist, Franco Freda, applying blackface to Monica Vitti.)

The Metamorphosis

In The Passenger, David Locke--like Vittoria-- will also usurp another existence. (David Locke’s name may itself be a hybrid of two preeminent Scottish and English philosophers of the Enlightenment, David Hume and John Locke, respectively.) The Girl in The Passenger will register at the Hotel de la Gloria at film’s end as “Mrs. Robertson.” In L'avventura, Claudia begins her transformation into Anna early in the film, to such a literal degree that Claudia begins to wear Anna’s very clothing. Guido Aristarco chooses to interpret Vittoria’s masquerade as an African woman, in part, as a Rousseau-like admiration for the “libertà dell’uomo selvaggio” / “liberty of the savage man” (woman!). More subtle pluralities of being and identity are also suggested, an example being Piero’s reference to himself early in the film as a gambler, and later, as a whore. The allusion to gambling will be reinforced later in L'eclisse when Vittoria finds a deck of cards in the apartment of Piero’s parents which she shuffles, as well as the large pictures of the face cards seen on the apartment wall. In L'eclisse, the stock market crash and the end of the film transforms the Italian proverb “Unlucky at cards, lucky in love” into the double-negative of “Sfortuna al gioco, sfortuna in amore.” Identity is plural, fragile, and subject to change.

Vittoria may know Piero or his type better than we realize. (Antonioni rarely allows us direct access to the minds of his characters.) Even if Vittoria has not seen Piero ogle at the nursemaid in the Eur, caught him trying to steal a peek at her own breasts, witnessed him patting a woman on her rear in the Bar della Borsa, or had an opportunity to observe him so cruelly slay the Bestiola, Vittoria may be able to recognize a tiger by his stripes. Unlike Giuliana of Il deserto rosso, Vittoria in all likelihood knows that 2 and 2 is 4 when it comes to the sexual arithmetic of men like Piero. While Vittoria and Piero briefly sit and talk on the living room couch in the apartment of Piero’s parents, Vittoria asks Piero a simple, direct question that many lovers in a time when Eros is so sick may need to ask of one another more often: what were you doing last evening? (“Cosa hai fatto ieri sera?”) The question inadvertently echoes the lyrics of the Edwardian song, “Who Were You with Last Night?”:

Who were you with last night?

Out in the pale moonlight?

It wasn't your sister, it wasn't your ma,

Ah! ah! ah! ah! ah! ah! ah! ah! ah!

Who were you with last night?

The Photographer of Blow-Up brusquely asks of the model, Verushka, “Who the hell were you with last night?” (See Garner and Mellor. Antonioni’s Blow-Up. Pages 18-19). Verushka might ask the same of the Photographer and be surprised to learn that last night he was disguised as another person in a doss house. The real question will, however, not pertain to the past, but to the future: where after the crisis he has suffered will the Photographer be on the evening that will follow the end of Blow-Up? The same question applies to Vittoria and Piero—who like the Photographer—have disappeared at the conclusion of their respective films and vanished into a black night of uncertainty and blasted hopes.

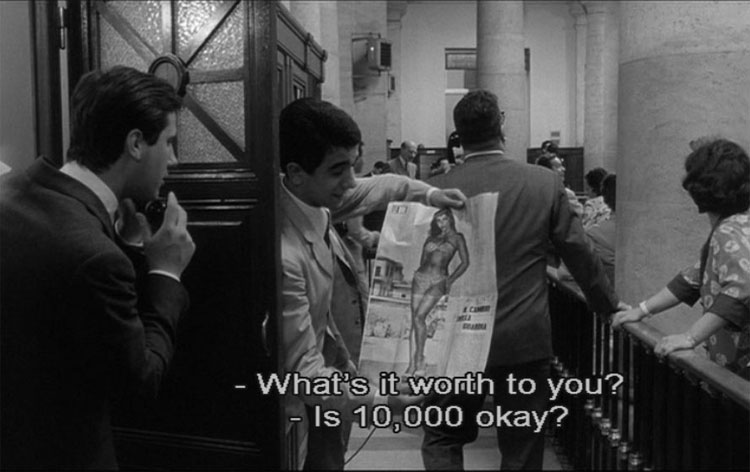

As has already been discussed in Endnote #18, Vittoria’s question as to the whereabouts of Piero on the preceding night may be of critical importance. Piero responds with a characteristic non-response: “Ero a cena con 7 o 8 miliardi.” (“I was dining with 7 or 8 million [lira].”), interchanging people with money. Vittoria continues the transformation of one thing into another when she responds, “Ah, con una squillo?!” (“Oh, with a call girl?!”). Piero then responds, “E chi ha tempo di andare con una squillo? La squillo sono io!” (“Who has time to go out with a call girl? The call girl, that’s me!”). Piero’s accuracy in identifying himself as a whore--a joke à la Freud revealing a subconscious auto-diagnosis--is bolstered by events throughout the film. Arrowsmith makes the point that the Borsa itself is infused with sex and thus, is a kind of whorehouse. And it is in such a whorehouse that Vittoria and Piero first meet.* Within moments of our first introduction to the Borsa, an unidentified character holds up a cheesecake picture of a girl to a colleague and asks, “Quanto paghi?” (“How much?”).* It is only minutes later that this reduction of a woman (all pornography--including that of a miniature woman trapped in a pen--concerned with the reduction of women) will spring to life in the guise of Vittoria. In the Borsa, sex is in the air, as if the market’s ventilation system were an atomizer spraying aerosolised pheromones or aphrodisiacal gasses into the hall. Gambling casinos are similar insofar as good business is promoted by concocting an intoxicating mélange of money disguised as poker chips and pretty bar maids—squeezed into skimpy costumes as if the women were shrink-wrapped or stuffed into the skintight garments with a shoehorn—fluttering about, baring their décolletage, serving free drinks: all to soften up the patsy. Even in the middle of “il crollo” (the crash), the libidinous drive hurtles forward, unabated. While the market is disastrously crashing all around him, it remains a high albeit completely digressive priority for Piero to remark to an unidentified client of his: “Ah, I saw you last night. You

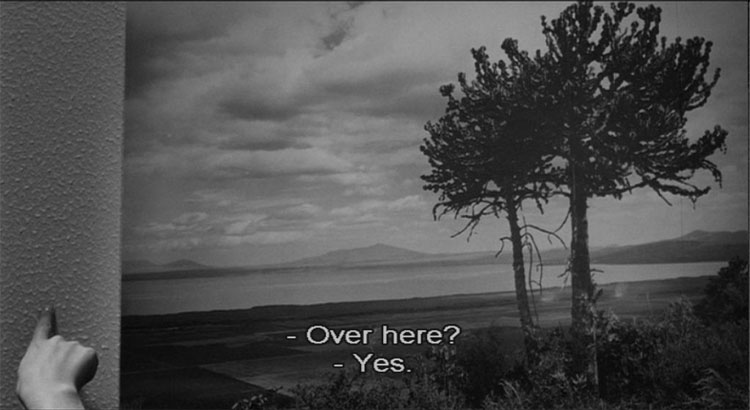

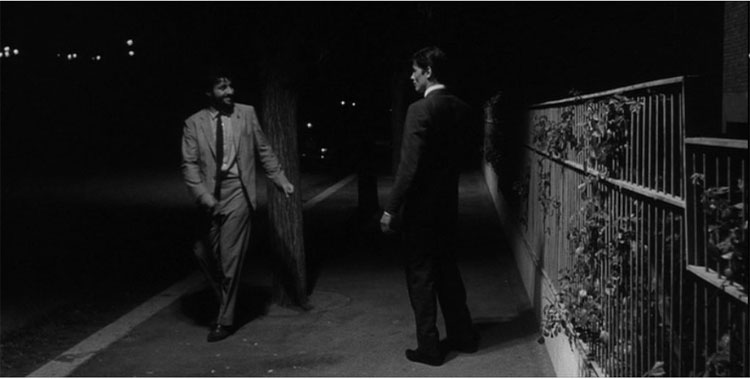

had some nice moves going on there. I know that girl.” (“Ah, ti ho visto ieri sera. Bel movimento ci avevi. La conosco quella ragazza.”), to which the man responds, “Forget about that. Think about the movement going on here.” (“Lascia perdere. Pensa a questo movimento qui, adesso.”). At one point, an unidentified trader who is quite effeminate swishes through the Borsa asking, “Giovanotti, chi viene in camera con me?” (“Young men, who will come to my room with me?”). When, in the heat of the Borsa shortly thereafter, Piero excitedly whispers something in the ear of an assistant from his firm, Dino, Piero’s embrace of this man is as close and passionate as any contact we will ever directly witness between Vittoria and Piero. Antonioni explicitly describes in his 1964 published screenplay (Sei film, p. 394) that in the Borsa there stands “un grupetto di donne [che] segue la discesa dei pressi con orgasmo” (“a group of women who follow the falling prices as if in orgasm”). While on the phone in the Borsa speaking to an operator during the middle of the crash, Piero screams into the receiver, “Pronto. Signorina, sei una troia, se non mi dai Milano subito!” (“Hello, operator. Miss, you are a whore if you can’t connect me immediately with Milan!”).20 Women never appear far from Piero’s mind. At the conclusion of the day of the market crash, while in his office, Piero suddenly stops his business dealings and makes what seems like an impulsive, impromptu date in a brief telephone call with the Bestiola. (This telephone conversation, in the vernacular, is no more than a tawdry, literal “booty call”; if L’eclisse took place in 2010, Piero would be pulling out of his pocket his “telefonino” [mobile] and making a monosyllabic, ungrammatical, acronym-filled form of texting [SMS], a “sext message” soliciting a “hook up.”) Later that evening, sitting exhausted at his desk he announces that he is “too tired to lift a finger.” Nevertheless, Piero suddenly remembers the rendezvous he has made with the Bestiola, and bounds out of the office with a surge of libidinous energy. (Ironically, when Piero bolts out of the office, he leaves behind one crash--that of the market--only to confront shortly thereafter another crash, that of his Alfa.) Can there be any doubt that Antonioni gave to Delon a (s)explicit, directorial command to pat the rear end of an unidentified woman in the bar of the Piazza di Pietra, or to ogle at the legs of the nursemaid pushing the baby carriage in the Eur? (The nursemaid also raises her skirt to adjust a stocking, the kind of act that could send all of the men of Messina wild with lust in L’avventura.) In this regard Piero resembles other males in the “tetralogy,” particularly Sandro of L’avventura, who is an architect by trade and an erotomaniac by being.* (Indeed, not five minutes may pass in L’avventura without some-man-making-some-move-on-some-woman.) In L'eclisse, even the mysterious Franco apparently tries to seduce Vittoria in his brief telephone call with her. In Antonioni’s last complete film, Par-delà les nuages (1995) , the final story told in this omnibus film--thus, the last tale ever told by Antonioni--is that of a young man who tries to draguer a young woman on the streets of Aix-en-Provence (reminiscent of the conclusion of Le amiche when in an absolutely digressive manner a stranger tries to pick up Clelia at the Torino Porta Nuova train station). In characteristic Antonionian fashion we discover at the end of this last story in Par-delà les nuages that any chance of love is doomed to failure. (In 2004, Antonioni contributed one segment to the film, Eros, in which, characteristically, a question mark hangs like the Sword of Damocles over a couple in amorous conflict.) Not only are people confused with one another, but places merge, one with the other as well. Riccardo refers to the rendezvous site for his meeting with both the Bestiola as well as his later meeting with Vittoria as “il solito posto” (“the usual place”). In one case the “posto” is the sidewalk outside his office, while in the second case the posto is aside the water barrel of the Eur intersection. Late in the film, in Vittoria’s apartment, we see her figure framed against the wall behind her bed as she makes the abortive phone call to Piero. The wall paper bears a striking resemblance to the thatched, burlap or straw-like, construction material masking the fateful building by the barrel (a building which, thus, resembles the straw huts seen in the first Antonioni short film, Gente del Po as well as the thatched buildings that populate the African village in The Passenger). Piero’s office building, the site where we last see Vittoria and Piero, is also a construction site. Not only is the stairwell a peculiar maze of wooden slatterns (an elevator shaft being renovated?), but in Perry’s study of L'eclisse (quoted by Lyons), Perry notes that if one looks closely out one of the office windows covered with Venetian blinds, there appears to be scaffolding. In fact, Piero’s office contains the world itself: after hearing the door buzzer ring, Vittoria arises from the floor and walks past a small black statue--perhaps that of an African woman--placed upon a book shelf next to a globe of the world. Why are such objects, these particular objects, found in an otherwise sterile brokerage office? In Marta’s apartment one entire wall appears to be a photo mural of an African scene, offering the illusion that only a single step is necessary to walk from Rome into the savannah. When Marta shows Vittoria a photograph of her farm in Kenya--a photograph without a frame--Vittoria’s finger shows us that the farm is actually several inches outside the left margin of the photo in the middle of a white field, a wall of the apartment (although, the farm is invisible--a spot on a blank wall--the photo prominently shows two large trees). Joan Esposito has noted that: Around Vittoria’s apartment at 307 Viale dell’Umanesimo, a map of the EUR lists Africa Avenue, Kenya Avenue, Aeronautics Avenue, Art Avenue, Astronomy Avenue, Technique Avenue, Sports Records Avenue, Painting Avenue, Music Avenue, Esperanto Avenue, and Champions Avenue: a list which could be continued in this vein and which reads like a parody of the film’s script. If the EUR did not exist, Antonioni would have had to invent it. Esposito also reminds us that in the original “Lane” script, there was a scene that was shot and later edited out in which Vittoria and Anita visit the Verona Museum of Natural History. Observing the fossil record, Vittoria realizes that Verona once contained palm trees and crocodiles (or as Esposito remarks, “[Verona once was] much like Marta’s Kenya.”). In this light, Vittoria’s transformation into an African women is but an atavistic regression to an earlier form. Even Italy doesn’t seem like Italy when Piero remarks, “Mi sembra d’essere all’estero.” (“I feel like I’m abroad.”). A more psychological take on this latter comment would be that Piero is experiencing derealization or depersonalization, something that Giuliana of Il deserto rosso will suffer even more acutely from. (Piero may have more psychological problems than mere narcissism [see Note 17]; Antonioni pointedly shows Piero both biting his finger nails as well as taking possible sleeping pills at bedtime, small clues that point to a more generalized anxiety.) The most elaborate metamorphosis directed by Antonioni in L'eclisse concerns the relatively lengthy matter concerning the Drunkard. “L’ubriaco” (“the Drunkard”) appears on scene in an unanticipated and unmotivated manner, his appearance seeming capricious and digressive. On close inspection, we see Piero appearing at night, uninvited, waiting on the sidewalk beneath Vittoria’s apartment, reprising the analogous visit by Riccardo earlier in the film. Vittoria, hidden and peering from behind a curtain (as she did with Riccardo), recognizes Piero who--in turn--does not glimpse Vittoria. Piero then walks off the right of the screen, out of sight of Vittoria who remains standing, peering from behind the curtain. Piero then encounters the Drunkard, who then walks onto the screen from the right into Vittoria’s line of sight. Vittoria is momentarily confused, expecting Piero once again, but obviously encountering someone else (Vittoria yells down to the Drunkard, “Ma, chi sei?” [“Who are you?”], the response to which is an enigmatic shrug of the Drunkard’s shoulders). Antonioni shows us a kind of transmigration of souls in the instant when we first watch the Drunkard and Piero pass one another in opposite directions, an exchange of bodies that anticipates the exchange between Locke and Robertson in The Passenger. (As a professional broker, an “agente di cambio,” Piero has engaged, not in a stock, but a soul exchange.)* The Drunkard, née Piero, then steals the white Alfa (“stealing” is not the proper word since, the doppelgänger of Piero who has now taken possession of Piero’s body now “owns” the car). The “true” Piero (actor, Alain Delon) is nearly killed when the Drunkard almost runs him over, a near double suicide.21 A single death does occur in the eventual drowning of the Drunkard in the car in the lake. (If one accepts that there is a linkage between Piero, the Drunkard, and the cigarette matches [which “drown” in the water barrel], then a resonance exists between the two bodies of water in L'eclisse, the water barrel and the artificial lake of the Eur.) It may be no “accident” that the Drunkard drowns in the Alfa, as opposed to dying, for example, in a head on collision with another car.* Aside from again suggesting a terrible violence latent in the world of L'eclisse, I believe Antonioni’s primary goal for this quite complex and evidently costly episode regarding the Drunkard is the elegant exposition of the transformation of one man into another. The episode with the Drunkard is actually the culmination of a crescendo of several immediately preceding scenes involving the theme of “who’s who?”: the Bestiola followed by the blond cipher outside Vittoria’s apartment followed by the Drunkard. Boundaries between different people are as indistinct as the borders between objects and people. The episode involving the transformation of Piero into the Drunkard constitutes a baroque visual metaphor that depends on meticulous choreography and editing. Such a metaphor stands opposed to a more simple visual simile that Antonioni constructs involving Piero and a jockey riding in his sulky. When Vittoria and Piero meet at the water barrel for a second time, it is Vittoria who arrives at the barrel first. Piero then makes his appearance on stage in a distinctive manner. With the camera focused on Vittoria at the water barrel with her back to the street behind her, her front facing we the audience, we suddenly hear the distinctive trot of a horse. Vittoria turns away from us to visualize the source of the trotting sound. A shot from behind Vittoria over her shoulder reveals a jockey and his sulky briskly traveling down the street from screen right to left. Vittoria follows the movement of the sulky turning her head to the left as the camera then in an autonomous fashion takes over the visual pursuit, panning from right to left leaving Vittoria behind and out of the frame. The camera then abruptly stops its pursuit when it perceives Piero standing in the middle of the zebra-lined pedestrian crossing, the jockey and sulky continuing their passage in the background behind Piero towards screen left. Rifkin (p. 77) refers to this momentary “intersection” of Piero and the jockey as a “visual juxtaposition.” Rifkin writes, “The association here between the trotter and Piero is that he, too, is a racer and a gambler working in the stock market, harnessing his manic energies to make money.” This brief conjuncture of Piero and the jockey’s respective orbits is of a much simpler order as compared to the interface between Piero and the Drunkard that had occurred earlier in the film. In the case of Piero and the Drunkard, their conjoining is first witnessed in isolation by we the audience without any participation by Vittoria. In the next shot of that scene we are then projected into Vittoria’s consciousness and adopt her POV as she suddenly sees the unexpected Drunkard and not the anticipated Piero walk past her window. In the case of Piero and the jockey, we have a kind of simple cinematic simile: Piero is like the jockey. In the case of Piero and the Drunkard, the perceptual misunderstanding underlies a more complex cinematic rhetoric, one involving an interchange of identities or of souls. There is a very early precedent in Antonioni’s career--a kind of mirror or inverted scene that anticipates the later scene concerning the Drunkard in L'eclisse--that occurred in a student short Antonioni made while briefly at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in 1940. In this student project, perhaps the first “film”ever shot by Antonioni, a woman is seen handing over money to another woman who is a blackmailer. Although both characters--victim and blackmailer--were played by the same actress (Antonioni’s future wife, Letizia Balboni), no apparent seam or break occurred during the transfer of money from one person to the other. Biarese and Tassone, as well as others, have remarked that none of the judges at the film school could explain how Antonioni had apparently filmed one actor simultaneously playing two parts. (The “trick” was that a subtle cut had indeed been made that was invisible to the eye.) The student short anticipates by some 20 years the scene of the Drunkard in L'eclisse. In the former film one actor plays two parts. In the latter film two actors merge into one. This is, of course, an incessant theme for Antonioni. In Il deserto rosso Valerio proves to his mother in his game with the coloured drops of water that one and one isn’t two, a lesson that Locke and Robertson repeat in The Passenger. In an old review of L'eclisse from the journal Reforme--an extract of which has been recently reprinted--the author writes: Lors d’une éclipse, pour un observateur, deux astres semblent n’en faire qu’un . . . Pourtant ils continuent leur course régulière et s’éloignent comme les héros d’Antonioni. (“During an eclipse two bodies seem as one, only to then separate from one another as happens with Antonioni’s characters.” [Quoted in L’Avant-Scène Cinéma, 1993]). If Antonioni invites us to incorrectly recognize people in L'eclisse, he also denies conventional expectations in other ways. In the opening scene Riccardo asks Vittoria, “Hai qualcuno che ti aspetta?” (“Do you have anyone waiting for you?”), to which she appears to sincerely respond, “No.” (Il grido, like L'eclisse, begins on a note of rupture between a man and a woman; in Il grido, however, the character, Irma, played by Alida Valli, is cheating on the character, Aldo, played by Steve Cochran.) Despite the fact that in L'eclisse, Vittoria denies that she is cheating on Riccardo, someone is, of course waiting, only scant cinematic minutes and feet away.

The market value of cheesecake

In the middle of nowhere

Soul exchange

The ever-present proximity of death, sealed by a metaphysical high-five

Vittoria has no romantic respite in all of L'eclisse: she meets Piero on the same day that she and Riccardo break up. L'eclisse is not the story of “at-long-last-love,” but that of immediately stumbling from one bad relationship into another. Dalla pentola alla brace (“from the frying pan into the fire”). The phenomenon of the “ricochet romance” or “ merry-go-round of love” (La ronde) has already been discussed earlier in this chapter and is a motif in the the majority of Antonioni’s major films. No one stops to take so much as a breath between ending one doomed affair and the driven, incessant repetition/compulsion of beginning another equally dissatisfying relationship. Antonioni doesn’t like to lecture the viewer. He would seem to cling to the dictum that “If you want to send a message, call Western Union.” Nevertheless, we the audience have the tricky ability to choose whatever message we—for our own reasons—wish to receive. No matter how much we as viewers comprehend or empathize with Antonioni’s characters, we may only perceive Antonioni’s films from a standpoint outside of the films, a vantage point independent from whether Antonioni expressly wishes to teach us anything or not, or whether there is any evidence in the films to support our interpretations. Antonioni’s characters, however, seem to have great difficulty at learning anything from “within the films.” One may go so far as to conclude that this is a central “learning point(s)” that characterizes Antonioni’s films: the protagonists in the film learn nothing, the audience is often unsure what the films “mean,” and in both the fictional and real worlds, we are left in the end with . . . nothing. If anything at all has been gained it is, ironically, a sense of loss.

Ironically, it is on Vittoria’s errand to the Borsa to tell her mother that she has broken up with her lover, Riccardo, that she meets for the first time her new lover, Piero.22 Ensconced in Piero’s boyhood room, Vittoria retreats behind a locked door only to be surprised by Piero sneaking in through another entrance. Later in the film both Vittoria and Piero rendezvous at the water barrel for a second time, no evidence ever explicitly presented in the film that they have agreed to do so. (Likewise, no explicit invitation is ever extended by Anita to Vittoria that Vittoria accompany Anita and her husband on the flight to Verona.) A similar narrative ellipsis occurs when Vittoria and Piero meet at the Eur lake as both the Alfa and the dead are being raised. We the audience have never witnessed any prior agreement to meet at the lake. At the conclusion of the film, when Vittoria and Piero do agree to meet at the barrel, neither shows up. (As Sitney has written, it is the audience who is stood up. Or as Perez remarks, only Antonioni’s camera keeps the final appointment.*) The entire film might be viewed as a prelude to this final denial of expectations, this deception, the eclipse.23

Ted Perry, as well as René Prieto, both believe that Vittoria and Piero had indeed made plans for the second meeting by the water barrel, and that the omission of a scene in L'eclisse demonstrating such an agreement constitutes a typical Antonionian ellipsis: “The viewer may not see in L'eclisse the moment when Vittoria and Piero agree to meet at that particular street corner, but the action suggests clearly that such a decision took place.” The dialogue between Vittoria and Piero at their second meeting by the water barrel indeed does suggest that Perry and Prieto may be correct, that Vittoria and Piero had made a prior agreement to meet at the Eur intersection:

Piero: “Sei già qui.” (“You’re already here.”)

Vittoria: “Da un quarto d’ora.” (“Yes. I’ve been here for 15 minutes.”)

Piero: “Ah! Credevo di essere in anticipo.” (“Oh! I thought it was I who was early.”)

Vittoria: “Sono io che sono arrivata prima.” (“No. It’s me that arrived first.”)

And yet, the alternate possibility--that Vittoria and Piero simply show up without any prior arrangement--seems also conceivable and strangely appropriate . . . appropriate that these two strangers should be compelled for reasons they do not understand to be drawn back to the undistinguished site where The End will occur. The question also arises as to why Vittoria and Piero would ever agree in the first place to arrange for a date by a half-finished, dirty construction site in the Eur alongside a water butt filled with stagnant water. The answer, of course, is that Antonioni--not the young couple--made the decision as to where they should meet, a decision based on thematic concerns as opposed to what two lovers in real life might do. Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday do not frolic in the Eur. (Although in Antonionian fashion, the future together of these latter two star-crossed lovers is eclipsed at the end of their film.) Antonioni’s choice of the Eur is a modern one, a site that removes his characters from Roman antiquity, placing them ever more east of Eden.24 Although L'eclisse is a story of love among the ruins, the ruins--with the exception of the Parco Buoi of the Borsa--are not those of ancient Rome, but those of a more modern wasteland, the Eur.* Together, the old and new Rome of L'eclisse reprise a vision of another damned city, Metropolis. (In La dolce vita Fellini placed the murderer, Steiner, and his apartment in the Eur: from the balcony of Steiner’s modern apartment one may see the Eur water tower in the background. Indeed, because of the unique character of the Eur it has been the shooting site for over 100 films, the subject of a recent book by Laura Delli Colli.) Similarly, in The Passenger Locke first glimpses the Girl not by some fabled, historical site of London immediately recognizable to most viewers, but in a modern architectural context, Bloomsbury Centre. Mancini and Perrella (p. 427) acknowledge this tendency of Antonioni to choose unusual shooting sites, citing among several films, the Italian segment of I vinti with Antonioni’s choice of the “atypical Roman neighborhood of Coppedé.” Additionally, much of this latter segment of I vinti is expressly filmed against the backdrop of construction sites in the vicinity of Rome--including San Paolo on the Tevere--an anticipation of the importance of a construction site in L'eclisse. (The opening scene of L’avventura takes place at a construction site.) Architecture is an abiding concern of Antonioni. The house where Vittoria and Piero first make love is haunted by the portraits of the dead and dying, a love affair consummated in a charnel house. Antonioni has a particular concern in many of his films with the aestheticization of the banal, the beautification of the ugly, a preoccupation he shares with Ozu in the representation of factories as objects of beauty, something we witness in Il deserto rosso or, in the case of Ozu, in the image of towering chimneys of the garbage processing plant in The Only Son (1936), an image Ozu resurrects at the very beginning of An Autumn Afternoon some 25 years later near the end of his career.

A more important uncertainty concerns Vittoria and Piero’s final appointment at the water barrel. In their last scene together, before parting, while they stand by the front door of Piero’s office, Vittoria and Piero agree to meet that evening at the specific time of 20.00 hours at the “solito posto.” In the soon-to-follow 6 and a half or so minutes that comprise the mysterious coda of the film (depending on which edited or unedited version of L'eclisse is being viewed), there are no firm indications presented to the audience as to the exact time when the coda is taking place (or even if it is the same day)!

For cinematographers, sunset is sometimes referred to as the “magic” or “golden” hour, a particularly hazardous time to shoot a scene insofar as there is little light left to illuminate the scene and such light is inconstant and fades quickly. If a repeat shot or entire scene is required to be refilmed, one may need to wait 24 more hours and even then, the conditions may not be the same for purposes of continuity and the like. Pure night shots are easier to film insofar as rapid fluctuations in light such as occur at sunset generally do not occur (the changing of moonlight, for example, occurring more slowly and with less intensity relative to the rapid, dramatic changes in illumination of the final setting of the Sun). One may, indeed, simulate a night shot using the cinematographic technique of “la nuit américaine”: shooting during the daytime employing filters and under-exposure of the film. In the final minutes of the coda of L'eclisse, it is sunset, the magic hour, the sky darkening, but not yet black, cars now with their headlights on, streetlights beginning to illuminate. When the final image of L'eclisse is extinguished, we do not know the precise time. This is critical because, if sunset has occurred in Rome on 10 September 1961 (the date of the weekly periodical being read by the man exiting the bus in the coda of L'eclisse)* at or before 20.00 hours, then the film does not confirm that Vittoria and Piero have definitely stood each other up. L'eclisse may simply have ended before 8 p.m. As the unidentified man on top of the Eur building points with raised hand to the person (a woman?) next to him, he might be saying, “Look, here come Vittoria and Piero. The film we find ourselves in will end before they arrive on time at their solito posto.” The earlier that sunset had occurred before 20.00 hours, the more difficult it is to be certain that Vittoria and Piero may have truly “missed” their appointment. For example, we know that it is quite dark at the conclusion of the film and that sunset appears to have perhaps even concluded. If this beginning of true nighttime occurred at approximately 19.30, then we the audience simply will not have been privileged to witness what occured at the construction site at the appointed time of 20.00 because it was not “contained” within the temporal limits of the film. Vittoria and Piero may both have kept their appointment or not, but either possibility will be “off screen and beyond time.” If, however, nightfall has occurred later than 20.00, say, at 20.30, then there is more reason to speculate that both Vittoria and Piero have missed their appointment because we never witness them in the coda of the film.

Both Vittoria and Piero appear punctual, having arrived perhaps at their previous appointment at the barrel early. I suspect that the overwhelming majority of critics and viewers of L'eclisse interpret the coda as indicating that Vittoria and Piero have expressly chosen--for whatever reason--to not keep their appointment. Such a conclusion has been my own personal bias, one that permits a more sombre and enigmatic interpretation of the end of the film. In the written screenplay published in 1964, this would appear to be Antonioni’s own intention when he writes, “Non c’è né Vittoria né Piero: nessuno dei due è venuto all’appuntamento.” (“Vittoria and Piero aren’t there. Neither one has shown up for their appointment.”) Tailleur and Thirard note, however, that Antonioni rejected the explicitness of this ending, and made the conclusion of L'eclisse much more open-ended and ambiguous. (Regardless, deconstructive criticism would deny the relevance of authorial intent.) Movies, like lives, end, but audiences wish to know what happens next in the “Great Cinematic Beyond” just like people who have never stepped inside a cinema ponder the issue of an afterlife. This is particularly true of L'eclisse, where on an elementary level Antonioni—by deliberately making the conclusion of his film enigmatic—piques our curiosity. We may wish to know what will happen to Vittoria and Piero, but this pertains to a time and a place we shall never come to know. We have lost Vittoria and Piero to the same degree that they have lost each other.

In addition to the uncertainty as to when precisely L'eclisse concludes, there are at least four other factors that complicate the interpretation of the conclusion of L'eclisse:

Firstly, portions of the coda of the film were cut by the producers. Secondly, the conclusion of L'eclisse--according to Prédal and others--was originally intended by Antonioni to be even more overtly apocalyptic. Thirdly,we cannot be strictly certain that the evening we are shown at the conclusion of L'eclisse is the exact evening in which Vittoria and Piero have agreed to meet. As has already been mentioned, Antonioni is fond of ellipses. It is possible that such an ellipsis has occurred and that the evening we witness at the end of the film is an anonymous night occurring at almost any time in the summer of 1961 (The fact that the matches and stick of wood are visible in the barrel at least imply that the final scene takes place after Vittoria and Piero’s second visit to the construction site.) Fourthly, the coda was not shot in real time, nor was the camera trained only on the corner immediate to the water barrel and construction site. Both Vittoria and Piero could theoretically have met at the barrel in the these interstices of time and space and departed without our ever having seen them. A particularly beguiling ellipsis. There are, indeed, any variety of innocent explanations for why we do not see Vittoria and Piero at the conclusion of L'eclisse. Did they phone each other and postpone the rendezvous or change the place where they will meet? It is Antonioni and his camera who meet at the Eur at sunset. Outside of that parenthesis, there is an entire world. The common assumption that the ending is apocalyptic--like all assumptions that by definition fall short of certainty--comments more on our perceptions and desires than on what really occurred. A banal interpretation of the conclusion of L'eclisse that trivializes the film might be that Vittoria finally comes to her senses regarding what a schmuck Piero is and drops the bum. (Philip Strick does not refer to Piero as a “schmuck” or “bum,” but instead, as a “Malkara anti-tank missile.” I prefer “schmuck” to “missile.” I also prefer “schmuck” to a more clinical designation such as “narcissist,” for “schmuck” is a pejorative term that also refers to a part of Piero's anatomy that is near and dear to him.) The same interpretation applies to the beginning of the film and Vittoria’s abandonment of Riccardo. Antonioni carefully establishes the defective nature of each of Vittoria’s lovers; fortunately, with Piero it took her only days or weeks to realize how defective he was as compared to the years Vittoria appears to have thrown away on Riccardo. (As indicated by the calendar and clock visible in the first scene in the Borsa [Monday, July 10] as well as the date of the shot of the weekly periodical, L'Espresso, seen in the coda of the film [September 10], L'eclisse spans approximately 8 weeks, an amount of time that I imagine is close to the arithmetic mean for summer romances.) As a general rule, critics prefer profound interpretations that are gloriously implausible to trivial interpretations that are merely likely. I assume that Antonioni, himself, does not know where Vittoria and Piero are in the last minutes of his film. Antonioni sounds ultimately as ignorant as any of us who speculate on the meaning of the final moments of L'eclisse when he says, “La fine del film, anche se amara, non è pessimistica: si intravede una luce, una speranza, i due potranno trovare un domani quell’amore che oggi rifiutano.” (The end of [L'eclisse], even if a bitter one, isn’t pessimistic: one glimpses a light, a hope, that Vittoria and Piero might find tomorrow that love which they refuse today.” [Quotation cited by Aldo Bernardini referring to “Notiziario Cinematografico ANSA,” 25-7-61].) These are not the words of a director who intended the penultimate image of his film--a white light--to represent an atomic explosion; such words are as much a reference to the belief in Judaism that the origin of light is the lovemaking of angels. And as Paolo and Vittorio Taviani remind us in their homage to cinema, Good Morning, Babilonia (1987), what else are movies but light? Indeed, after their final parting in Piero’s office, both Vittoria and Piero briefly bear a small smile on their lips in the final images they cast on the screen, smiles that stand opposed to the anguished quality of their last embrace. Do Vittoria and Piero know something that we do not?

Sitney (p. 229, note #9) writes that “Although the film seems to take place in a few days, possibly from dawn on a Thursday to dusk the following Monday, the issue of L’Espresso seen in the final montage appeared about seven weeks after July 21, the date on the Borsa clock. Antonioni has telescoped the time of the film.” (Sitney is apparently referring to the second scene of the Borsa, the portrayal of the market crash that does occur on Friday, July 21. DSR.)

Time is running out . . .

for David Locke as well.

I do not know the precise date or time when Antonioni stood with his film crew in the Eur of the real world to shoot the coda of L'eclisse. Nevertheless, in the fictional world of Vittoria and Piero, on 10 September 1961, at the latitude of +41.54 N, longitude -12.29 East, at the current time offset from GMT of +2 (summer time), sunset occurred at 19 hrs 29 mins 28 secs (Astronomical Applications Department, U.S. Naval Observatory, Washington, DC).* A perhaps simpler manner of determining when the Sun sets in the fall is to remember that on the autumnal or September equinox day, sunset occurs at approximately 18.00, depending on such factors as precise latitude or whether one is on a hilltop or valley. Did Vittoria and Piero, in fact, keep their rendezvous after L'eclisse ended? And if they did not, where were they, where did they go? Did they elope? Ubi sunt, where are they? Mais où sont les neiges d'antan! I can imagine them now, together, in a hot sport convertible, top down, driving furiously north from Rome on Italy’s highway A1, aptly christened “l’Autostrada del Sole”--“the Highway of the Sun”--soon to traverse the South of France for the inevitable rendezvous with Daisy in Osuna, Spain, their honeymoon obliterated by a total lunar eclipse. (Caution: Plot Spoiler) Or did Vittoria and Piero not even make it out of the periphery of Rome, both dead after a catastrophic crash in a sports car driven by a man who loves to speed, their bodies in a stylized pose as was the fate of Camille and Jeremy at the end of Le Mépris? Born to Run, I wanna die with you Vittoria on the streets tonight in an everlasting kiss.

Although it is uncertain whether Vittoria and Piero do in fact stand each other up at 20.00 on a summer evening in Rome, it appears to be a fact residing in the real world that Antonioni himself did not show up for the screening of L'eclisse at Cannes on 2 May 1962, a festival at which the film won a “Prix du Jury” (“Special Jury Prize”) and was nominated for the Palme d’or. Bernardini writes (p. 191) that Antonioni did not attend the presentation of his film “. . . out of solidarity for his colleague, Mario Monicelli, whose episode had not been included in the film Boccaccio 70.” I do not know if the showing of L'eclisse took place in the evening at eight o’clock. However, if Bernardini is correct, then Antonioni joined Vittoria and Piero in not showing up at the Eur intersection that night in Cannes.

Because Vittoria and Piero’s existence is limited to the confines of L'eclisse--their death, like all fictive, cinematic lives, occurring at the conclusion of the film’s last reel--we will never know whether they will ever meet again. Will Vittoria and Piero ever even think of each other again? "Pour oublier il faut être deux." (“It takes two to forget.”) Biarrese and Tassone write on p. 121 of their book that Antonioni had actually wished to direct a sequel to L'eclisse, one shot from the perspective of Piero as opposed to that of Vittoria in “L'eclisse part 1.” Speculate, if you wish, and ponder a cinematic future that will never exist. Employ a pessimistic imagination to contemplate the intersection of Viale del Ciclismo and Viale della Tecnica at 08.00 the following morning after a failed rendezvous: apartments are emptying, workers are arriving at the construction site, nursemaids are pushing prams and sulkies are whizzing by. Be certain that none of these people at the fateful intersection will ever know that the evening before a fundamental rent in the fabric of the universe occurred: Vittoria and Piero failed to meet. L'eclisse might just as well never have been filmed. Or consider, more optimistically, that lovers commonly break up and get back together the following day. Imagine what might have become of Vittoria and Piero, whether they got back together or not. Or instead, look at La notte, the film by Antonioni which immediately preceded L'eclisse, and whose chief protagonists, Lidia and Giovanni, are in more than one way Vittoria and Piero’s closest cinematic relatives. Lidia and Giovanni have been married for many years, a marriage that is now moribund. La notte is both a meditation on the meaning of a dying marriage as well as a contemplation of death itself. The opening scene of the film is that of Lidia and Giovanni visiting a close friend and colleague who is on his literal death bed. Later that same day Lidia will begin her solitary peregrination throughout the streets of Milano which will conclude in a field at the periphery of the city near the Breda factory. Although Lidia’s wandering through Milano seems aimless, her eventual arrival at a specific field near the outskirts of Milano is quite deliberate. (She takes a taxi specifically to San Giovanni Street near the Breda factory.) This field is apparently the very spot that she and Giovanni frequented years ago at the beginning of their now lost love. Antonioni’s camera lingers briefly on a dilapidated building near the field which may have been their first residence. From a cheap roadside café Lidia phones Giovanni and informs him that she is at the “solito prato” (“usual field”; in Italian, so tantalizingly close to the “solito posto” [“usual place”] of Vittoria and Piero, the water barrel). Lidia asks Giovanni to pick her up in his car. She suggests falsely both to Giovanni and herself that she has arrived at this field purely by chance. Not long thereafter, Giovanni arrives and the doomed couple walk through a run-down area characterized--as the 1964 screenplay, Sei film, indicates--by a sense of “squalor and melancholy.” Instead of immediately returning to their modern apartment in central Milano, the couple wander as if dazed in some devastated outpost at the end of the world. Despite the fact that Lidia and Giovanni are no longer who they used to be, the promise of their love begun years ago now utterly unfulfilled, Giovanni remarks how, “Nothing has changed.” And yet, his inability to see how much has changed, how much has been lost, is not so complete that he is unable to see that the train tracks across which they walk are entirely overgrown with weeds and brush. This area, this “solito prato” is, of course, the “solito posto” of the Eur located some 500 kilometers to the south in Rome. This scene in La notte is, perhaps, as close as we will ever get to visualizing what a subsequent visit between Vittoria and Piero would have been like at the Eur intersection on the outskirts of southern Rome by a ramshackle construction site. I can only imagine that if Vittoria and Piero had ever married and subsequently found themselves some 20 years later back at their solito posto, the same thing that happened to Lidia and Giovanni would have occurred. Nothing, no longer a train nor even a bus, stopping at the spot.*

Beyond the end of time

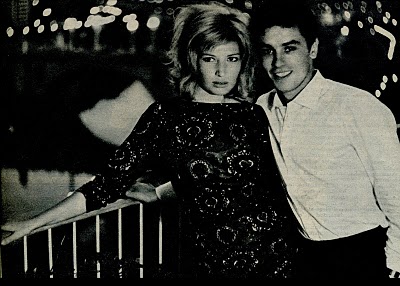

Perhaps all is not lost. Perhaps there remains one clue, one piece of errant evidence remaining that offers us a glimpse of Vittoria and Piero after L’eclisse and the world have ended. Such was the case with Blow-Up, when the photographer late in the film returns to his ransacked studio and finds one remaining photograph that had apparently accidentally fallen into a little crevice between two kitchen appliances, a rent in the fabric of the universe, an indistinct image that, at least, the photographer believes—rightly or wrongly—is the corpse he assumes is still in Maryon Park. There is an image I found—I suppose one may call it a photograph—that I accidentally stumbled upon lodged in a small, interstitial space from an Internet site (http://jacquelinewaechter.blogspot.com/2010/01/vittiun-po-della-sua-vitta.html [retrieved 22 January 2010]). The site refers to a trip that Alain Delon’s fiancée, Romy Schneider, made to Rome to visit Delon during the shooting of L’eclisse. The site mentions a night on the town in which Delon, Schneider, and Vitti went to a night club. The photo shows two people who I presume are Vitti and Delon. Did Schneider take the snapshot or was it Antonioni, the man who made masterpieces of world cinema, a small, hand-held camera with a flash gun in his hands who captured the image? The blogspot does not clarify whether Antonioni accompanied the woman he lived with at the time, Monica Vitti, to complete the pair of two couples painting the town red on a Roman summer evening. It is uncertain whether the expression on Vittoria/Vitti’s face suggests buyer’s remorse concerning, respectively, Piero—the man at her side in the photo—or, perhaps, the person who is taking the picture, Antonioni? The man in the photo smiling broadly who resembles Piero and Delon seems to be in character for either man—Piero or Delon—individuals one might expect would enjoy a madcap night of partying on the town. The woman who resembles Vittoria and Monica Vitti appears to still be in costume, perhaps wearing the very dress we see her wear in L’eclisse. Ultimately, I am uncertain if the photo is that of Monica Vitti and Alain Delon or . . . Vittoria and Piero. Regardless, the dizzying image of these two people is not in any version of L’eclisse that I have ever seen. Given, however, the uncertain provenance of the image and the unfortunate mutilation of L’eclisse in the editing room by the producers, it seems theoretically possible that this image was meant to be included in the final version of L’eclisse, but like Vittoria and Piero themselves, never arrived at 20.00 on 10 September 1961 or thereafter. The issue, to some degree, is whether the photo represents reality or not. I suppose that an even more fundamental epistemological or existential problem with the image is whether it even “exists” or not, or if it is the product of a “photoshop” computer air-brushing of black and white binary numbers and pixels. Few images in today’s world have not been modified in some manner in order to distort the primal apparition; for example, the beautiful, flawless young men and women that grace today’s glamour and fashion magazines do not exist as such. The difficulty in addressing the issue of this discrepant, little photo is that movies are real representations of fictional events, but that reality at times seems to be indistinguishable from a movie. One remembers Ronald Reagan’s inadvertent inclusion in his speeches and conversations of events that he believed had really occurred, but were in reality scenes from movies he had either seen or acted in. There is, yet, another consideration. Is this little picture of two people found floating in cyberspace the photographic proof—in a universe where celestial courts of law for good reason do not allow images to be admissible as evidence—of Vittoria and Piero side by side sometime after 20.00 on 10 September 1961? Let us put aside—if only for a brief reprieve—the tragic question of whether there is even one true thing, and ask instead, hope in our trembling voice, whether Vittoria and Piero, against all odds, made it . . . after all? Antonioni may have abandoned Vittoria and Piero but God may not be finished with them yet. The night is still young. Redemption comes in the blink of an eye. If you doubt this, ask David Locke, if you can find him.