ENDNOTES

One might discover the reason(s) that underlie Japan’s love of L'eclisse in the unusual “documentary-philosophical meditation,” Chris Marker’s celebrated film, Sans soleil. In the film Marker refers to the “poignancy of things” in Japanese culture and belief, a concept referred to in Japanese as “mono no aware” and related to one of the central doctrines of Buddhism, “anicca,” the notion of the impermanence of all things. An Internet site, <http://www.karakuri.info/perspectives/> (retrieved 21 May 2004), states, “Buddhist thought is the view of the universe in constant flux, which emphasizes the idea that all living things perish or are transformed in the chain of existence. From this view comes a feeling for the ‘poignancy of things.’ ”

Marker briefly films an annual Japanese ceremony involving the burning of toy dolls as described on the Internet site <http://www.clas.ufl.edu/users/jshoaf/Jdolls/hina.htm>

(retrieved 10 April 2006):

“ ‘Doll burning ceremony’ (<http://www.hirotaya.com/kuyou.htm>) is a Japanese-text site that shows some kind of ceremonial cremation involving dolls. ‘Burning Dolls in Ueno Park’ is a (<http://www.planettokyo.com/index.cfm/fuseaction/detail/navid/6/cid/4/>) ‘traveler's tale’ of stumbling upon the annual September 25 ceremony in Tokyo. Another site, which is now gone, described in English the burning of dolls in hopes of conceiving healthy children. These ceremonies are quite separate from the March 3 casting of dolls on the water.

The Japanese hold ceremonial burnings of many types of objects--needles and umbrellas, dolls and toys, papers, letters, and various other tokens of work accomplished during the year. In some places there is an annual burning of Daruma dolls, which represent the year's undertaking.

To me, as a Westerner, the idea of crafting elaborate and beautiful dolls intended for destruction--by water or by fire--is strange, an idea to think about when I look at these delicate creatures which have a life of their own.”

In the voice-over narration of Sans soleil regarding the burning of dolls we learn:

And when all the celebrations are over it remains only to pick up all the ornaments--all the accessories of the celebration--and by burning them, make a celebration. This is dono-yaki, a Shinto blessing of the debris that have a right to immortality--like the dolls at Ueno. The last state--before their disappearance--of the poignancy of things. Daruma--the one-eyed-spirit--reigns supreme at the summit of the bonfire. Abandonment must be a feast; laceration must be a feast. And the farewell to all that one has lost, broken, used, must be ennobled by a ceremony. It’s Japan that could fulfill the wish of the French writer who wanted divorce to be made a sacrament.

In Kurosawa's Ikiru, the heartbreaking poignancy of objects and things is presented inconspicuously in the background of a shot taken in the Tokyo home of Watanabe during his wake. In the background behind a medium shot of Watanabe’s son and daughter, we see lying discarded in a closet-like storage space the remains of a life, objects devoid of ostensible value, mute, the remaining bits of debris that trace the outline of an entire existence: a framed certificate attesting to Watanabe’s work efficiency, his alarm clock . . . and the small, wind-up, white toy bunny--a doll of sorts--that led to his redemption. These worthless objects—floccinaucinihilipilification—are so priceless, approaching the significance of talismans, that Kurosawa subsequently shows us the briefest of insert shots of these objects, reemphasizing their inestimable value.

Japanese viewers may also have regarded the mutual failure of both Vittoria and Piero to keep their appointed rendezvous at the conclusion of L'eclisse in a different, more positive manner than Western audiences. The phenomenon of the “double suicide” of lovers has existed in Japanese culture for at least 400 years, dating back to the famous play by Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Double Suicides at Sonezaki (See Mori, Mitsuya. “Double Suicide at Rosmersholm.” Internet citation: http://www.ibsensociety.liu.edu/conferencepapers/mori.pdf [retrieved 28 May 2008]). In Japan, there has been a time honored custom condoned by some elements of society to commit Shinjū (“double suicide,” translated literally in Japanese as “inside the mind”) as a method to idealize star-crossed lovers, allowing such impossible love to transcend societal constraints or prohibitions related to caste, money, and the like. To this day there have been multiple film treatments of the subject, memorably Masahiro Shinoda’s 1970 Double Suicide. Vittoria and Piero may be seen as performing a kind of metaphorical, shared self-immolation at the conclusion of L'eclisse, one that frees them from the horror of the Borsa, from the “pathologic family,” from an Italy that itself had become part of a fallen world. (See Chapter 3 of this book for my discussion—from a more Western standpoint—of “the impossible ‘double-bind’: that for Vittoria and Piero--or any couple for that matter--to possess one another, they must break apart.”)

With the notable exception of The Passenger, Antonioni’s films are largely secular meditations. In L’eclisse, however, the Japanese viewer may have regarded the bowl of water that is the water barrel, and the objects within--the piece of wood, matchbook, and other jewels--as a Shinto shrine. Japanese admirers of L'eclisse may have seen the conclusion of L'eclisse as an Italian version of the recitation of dono-yaki that takes place in the Eur quarter of Rome on or about September 10 as opposed to September 25: the blessing of the debris that have a right to immortality, a broken piece of wood, a matchbook, a woman, a man.

There is a rich Occidental tradition regarding the “fragment” that informs Western literature, art, philosophy, architecture, and psychology. A 10-week course entitled “Fragments: Theory, History, Visual Culture” was given by Professor Sophie Thomas in the fall of 2007 at the University of Sussex in the UK. As of March, 2008, the 10-page syllabus was still accessible on the Internet and alluded to the mind-numbing number of academic and other works devoted to, for example, such important “passwords” of deconstruction as “trace, brisure, différence, espacement . . . .”

( http://www.sussex.ac.uk/gchums/documents/fragments_final_2007.doc [retrieved 19 March 2008].)

A hardback book entitled, Romanticism and Visuality : Fragments, History, Spectacle has also been written by Professor Thomas and published in 2008 by Routledge.

Thematic and stylistic continuity is a feature of all of Antonioni’s films. To offer but one early example from an entire career filled with such examples, I vinti--a film made by Antonioni over 50 years ago--contains within the first of its three episodes many of the principal themes and characteristics that will reoccur in all of Antonioni’s films to follow. The first shot of I vinti is that of an unidentified beggar singing a cappella a love ditty in the streets of Montmartre:

Mettez la tête par la fenêtre . . . Vous entendrez parler d’amour . . .

In the background a nun holding the hand of a child are seen climbing the stair walk of Passage Cottin. The camera will soon climb above the streets of Montmartre to an apartment where two young and hungry men plot the robbery and murder of their friend in order to finance a half-baked adolescent fantasy of escape with beautiful girls to Tangier. (Towards the conclusion of The Passenger, David Locke-Robertson proposes that the Girl flee to Tangier--a storied city in life and art for its connection with espionage--where he will rendezvous with her, a rendezvous like that of Vittoria and Piero which will never be kept.) The apartment is located directly across from an elevated train platform. Trains will be seen and heard through the window of this apartment at both the beginning and end of the episode as well as throughout the story. These beautiful and absolutely empty young men and women retreat with their unsuspecting victim to an Elysian forest in Varennes--outside of Paris and out of time--that will someday be transformed in Antonioni’s universe to a park southeast of London. A glider suddenly, unexpectedly, mysteriously swoops in over our shoulders and into the movie screen flying perilously close to the heads of the heroes and heroines to land in a clearing in the wood: a beautiful and thrilling image of flight that like so many of Antonioni’s images is so utterly gratuitous. The carnivorous heroine, Simone, encourages her would-be lover, André, to carry out this murder in Elysium, at the same time entreating him (in the version of the film dubbed in Italian), “Portami via! Portami via!” (“Carry me off! Take me away!”). Some two minutes later Simone finds herself alone in the woods with the intended victim, Pierre, to whom she repeats the exact same fickle mantra, “Portami via. . . .” André will soon shoot Pierre, the vanity of the act revealed by the discovery that the money found on Pierre’s body, like Pierre himself, is fake.

It is, of course, all there, the themes, the images, the seeds of everything that will follow in all of the remainder of Antonioni’s films. The offhand love song, a member of the clergy and a child, the desire for a different life in another place, anywhere but here, anyone but me. The sounds and images of the vehicles of escape, trains, planes. The disaffected. Deception, betrayal, and adultery. And finally, death in the afternoon, death--as John Freccero reminds us--in Arcady, the French episode concluding in early evening as darkness envelopes the world, a train passing nearby in the night. (In the third and last episode of I vinti, a train passes in the background just before Aubrey Hallen strangles the prostitute in the park of Saffron, England. All three of the film’s episodes concern a murder. The last word of the film--uttered by the London journalist, Ken Wotten--is “death.”)

If I vinti, made in 1952, looks forward to all of Antonioni’s subsequent movies, then Antonioni’s last complete film, Par-delà les nuages--made in 1995 in collaboration with the German director, Wim Wenders--may be seen as a movie which looks backwards, a kind of catalog of the various cinematic gestures that Antonioni has made in a career of more than 50 years, a vanity project approaching caricature. The film consists of a series of vignettes, all of which concern perhaps the most abiding of Antonionian themes, the failure of love between a man and a woman. The first vignette with the apt title, “Cronaca di un amore mai esistito,” harks back to the title of Antonioni’s first feature film made in 1950, Cronaca di un amore, and repeats essentially the story of Vittoria and Piero: an attractive young man and woman fall in love and separate for unclear reasons. Other, more trivial similarities between Par-delà les nuages and L'eclisse include a kiss across a pane of glass between the characters played by Fanny Ardant and Peter Weller, reprising the similar sterile kiss between Vittoria and Piero that occurred twice in L'eclisse thirty four years earlier. (In Busby Berkeley’s musical extravaganza, Gold Diggers of 1935, in the dream sequence of “Lullaby of Broadway” the character played by Dick Powell kisses the Wini Shaw character across a plane of a glass door; the Powell character then opens the door accidentally pushing the Shaw character off a skyscraper’s balcony to her death. A “kiss of glass” also occurs in the legendary 1950 Japanese film regarding tragic wartime love by Tadashi Imai, Till We Meet Again [Mata au hi made], as well as the box office Italian comedy hit of 1957 by Dino Risi, Poor but Beautiful [Poveri ma belli].) CAUTION: SPOILER ALERT: The end of one of Antonioni’s last films, Il mistero di Oberwald [1980], is reminiscent of the shot of Vittoria and Piero trying to kiss through a pane of glass. In “Oberwald” the film ends with the two mortally wounded, strange variant of doomed lovers prostrate on the ground, desperately trying to touch each other’s fingertips, just out of one another’s reach.

Out of touch . . . forever

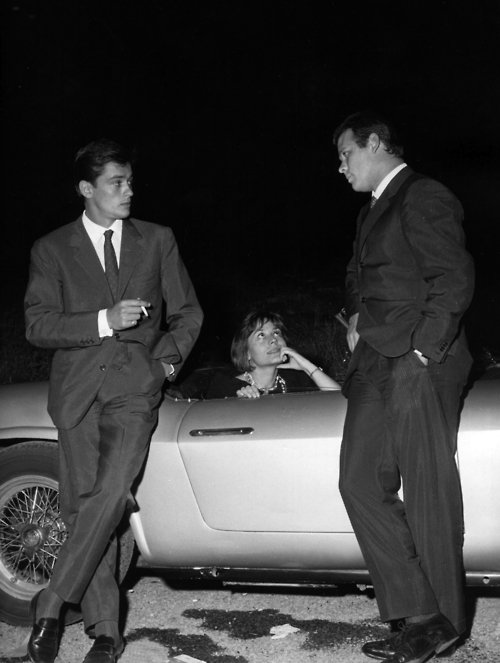

Many similarities and repetitions exist between L'eclisse and other films by Antonioni. Piero, for example, reminds us of other male protagonists in Antonioni’s films such as Sandro (L’avventura). Similarly, Vittoria reminds us of both Claudia (L’avventura) and Lidia (La notte). Indeed, the problematic issue of love between a man and a woman is a central concern in virtually every film Antonioni has ever directed. In the second documentary Antonioni made in 1948, Nettezza urbana, there is a brief scene-shot of a man and woman engaged in a heated argument--Antonioni’s proverbial couple-in-crisis--while crossing the Ponte Cestio, the piazza of the Basilica di S. Bartolomeo on the Isola Tiberina in the background. The man tears up a piece of paper, the remnants of which are then swept up by a “dustman,” the same image—bits of paper which will be cast to the wind—seen in other films of Antonioni (Il grido and L’avventura). The couple’s argument occurs in front of the very piazza where in 1960 in L’avventura stands Sandro’s apartment. This couple of Nettezza urbana are the forebears of Claudia and Sandro, of Vittoria and Piero, the summary statement for all of the failed couples in all the films to come. In Antonioni’s contribution, “Tentato Suicidio,” to the omnibus film, L’amore in città, the suicidal woman “played” by Rita Josa stands by the Ponte Palatino with the Isola Tiberina again in the background while an unidentified man ogles, almost salivating, at this tragic woman, someone he does not know. What to this needy man is a mere piece of ass is, instead, a human being who wishes to die. (See the Internet site, retrieved 17 November 2009: <http://www.isolatiberina.it/Movie_i.html> ©Copyright by Bruno Leoni for screen shots of the Isola Tiberina taken from the above and other films.) The theme of metamorphosis and transformation in L'eclisse, especially as suggested by the segment of the Drunkard, occurs in Il mistero di Oberwald (in which the queen played by Monica Vitti first sees Sebastian, her would be assassin, as he crashes through a door on which is painted an image of her dead husband, the king) and foreshadows all of The Passenger . Effacement and disappearance characterize the endings of both L'eclisse and Blow-Up. Both Vittoria and Piero suffer the same fate as Anna (L’avventura) and Mavi (Identificazione di una donna): they vanish. Flight and escape are a leitmotif of many of Antonioni’s films, and are explicitly highlighted by travel in a small plane in both L'eclisse and Zabriskie Point. A concern with nature with great emphasis placed on trees and the wind occurs in L'eclisse and Blow-Up. After our last view of Vittoria we see the object of her regard, a wall of trees, which is also the panorama that opens the film immediately following L'eclisse, Il deserto rosso. The beginning of L'eclisse--which takes place at dawn--also follows upon the heels of Antonioni’s immediately preceding film, La notte, which also takes place at dawn. In this regard there is no seam between the end of one film and the beginning of another. Il deserto rosso also portrays a universe of factories, machines, and things, has a hut one wall of which is painted with an African mural with zebras, and in the Sardinian fantasy has rocks which resemble human beings. The opening film credits of both L'eclisse and Il deserto rosso contain musical elements of both the human voice and modern instrumental music. Seemingly tiny repetitions occur such as the old man of Lisca Bianca (L’avventura ) and Marta (L'eclisse), both of who speak their hybrid “Itanglish,” or the word “bestiaccia/bestiola” which is pointedly used to describe an Italian Greyhound in L’avventura and a woman in L'eclisse. In the early documentary, La funivia del Faloria, Antonioni gained experience in filming atop the cabin of a ski tram at Cortina d’Ampezzo, experience later put to use filming atop the aerial tram from which David Locke spreads his wings above Barcelona’s harbour in The Passenger. In a larger sense, L'eclisse--like so many of Antonioni’s films, beginning with his first feature length film, Cronaca di un amore--is a mystery. Lastly, because there are not even rigid boundaries between one Antonioni film and another (one speaks of the “tetralogy” of L’avventura, La notte, L'eclisse, and Il deserto rosso, as if they were separate chapters in a single work), one might wonder if there was a wry smile on Antonioni’s lips as he linked the amphora, ashtray, and guitar across a distance of 1000 miles between Lisca Bianca and London, over a duration of 7 years?

Bruce Kawin in his remarkable book, Mindscreen, discusses in detail the 1966 film by Godard, Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle. It is almost as though Kawin were writing of the 1961 film by Antonioni, L'eclisse. This may not be surprising if one remembers that Godard himself interviewed Antonioni in 1964, and presumably was greatly influenced by him. Kawin writes:

Among other things, [Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle] offers a hard look at a political economy whose effect on character and society is such that objects seem more real than people, and people are treated, or treat themselves, as objects. Godard’s initial approach to these materials is to describe them ‘as both objects and subjects . . . from the inside and the outside,’ making no distinction between people and things. The latter method suggests an excellent metaphor for prostitution, but has several further aspects. The camera is as likely to study a beer tap as to hold on a human face, to follow a car through the wash as to record a conversation between the car’s owner and her friend. One of the film’s most brilliant meditations is on the pattern of bubbles in a cup of coffee--bubbles that at once suggest galaxies and subatomic particles, not only commenting visually on the nature of creation but also supporting Godard’s monologue: ‘Since I can neither elevate myself to Being nor sink into Nothingness, since I can neither get rid of the subjectivity that crushes me nor of the objectivity that alienates me, I must look around me at the world, mon semblable, mon frère.’. . . The people-as-things construct is examined throughout the film, most comprehensibly in Juliette’s visit to her husband’s garage, at the end of which the camera isolates the leaves of a large tree growing behind the MOBIL sign (a juxtaposition of two signs, or two ways of life, that is profoundly unsettling) and Godard, ‘overwhelmed by all these signs,’ and the difficulty of’ ‘rendering events,’ wonders whether he should have ‘spoken of Juliette or of these leaves.’ The culmination of this theme occurs near the end of the film, when Juliette gets in bed with her husband and, after a mild quarrel in which he exhibits his sexism (he treats her as an object no less than do her customers, or the economy, or the camera), lights a cigarette. Godard cuts to an extreme close-up, underexposed to such an extent that nothing is visible except the tip of the cigarette, which fills the screen, and that only when it is being inhaled on. The effect is that of a breathing cigarette, and it is an authoritative metaphor for Juliette’s life-process.

Godard’s entire film bears striking similarities to L'eclisse, not the least of which is a curious emphasis on a construction site in a Paris that appears more modern and sterile than classically beautiful, as well as the image of a cheesecake photo of a woman--seen through a magnifying glass--whose clothes slide on and off. As the hushed whispering voice of the film’s narrator--presumably Godard--tells us:

Objects exist, and if we pay them more attention than we do people, it is because they exist more than those people. . . Dead objects live on. Living people are often dead already. To create a new world where man and things are in harmony, that is my aim, as much political as poetic, for it explains this passion for expression. Whose passion? Mine: writer and painter.”

Although many directors have praised Antonioni’s filmmaking (Biarese and Tassone in their book on Antonioni list several directors including such discrepant filmmakers as Kurosawa, Rohmer, Tanner, Altman, and Satyajit Ray), it is less easy to define what specific influence Antonioni has had on these and other directors. In particular, Angelopoulos, Tarkovsky, Tsai Ming-Liang, and Wenders have been described by various critics as directing films reminiscent of those of Antonioni. In my opinion there are strong similarities in style and content between Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7 and L'eclisse, both films made at approximately the same time. Remarkable similarities also exist between the more recent 2005 film, La moustache, by Emmanuel Carrère, and both Blow-Up and The Passenger. Likewise, Wenders’ 2008 film, Palermo Shooting, bears similarities to these latter two Antonioni films. The title of the film, Palermo Shooting, may be both a play on words and an allusion to Blow-Up, the main protagonist of Wenders’ film being a fashion photographer with higher artistic ambition who is “shot”. Palermo Shooting is expressly dedicated to both Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni which the credits of the film state both died on the same day during the preparation for Wenders’ film.

I have already mentioned the disparaging explicit reference that the Vittorio Gassman character, Bruno, of Il sorpasso utters regarding L'eclisse (vide supra, Chapter 1). The entire narrative of Il sorpasso roars with a tachometric rev when Bruno stops his sports car on a deserted Roman street during Ferragosto and drinks from a water barrel that for all intents and purposes was plucked by a crane from the construction site of L’eclisse and plunked into Il sorpasso. As fate would have it, the water barrel is directly opposite an apartment building in a window of which Bruno spies the ingenuous, young, law student, Roberto, played by Jean-Louis Trintignant. Bruno yells up to Roberto to ask if he may use his telephone to call the “burina” (“bestiola”), Marcella, whom Bruno was supposed to meet at 11.00 in the morning. It is now midday, Bruno is running behind, and this missed rendezvous will, as in the case of L’eclisse, prove fatal.

Wikipedia (retrieved on 6 May 2007 notes another reference--in a different sarcastic vein--to Antonioni:

“He [Antonioni] was referenced in an episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus when Eric Idle, playing Inspector Baboon of Scotland Yard's Special Fraud Film Director Squad, Jungle Division, arrests someone accused of impersonating ‘Signor’ Michelangelo Antonioni. He [Eric Idle] continues an academic discourse of Antonioni's film career as the credits begin to roll.”:

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo_Antonioni>)

The “discourse”--retrieved from a different Internet site--is:

Inspector [played by Eric Idle]: “Shut up! (shoots her) Right, Akarumba! I'm arresting you for impersonating Signor Michelangelo Antonioni, an Italian film director who co-scripts all his own films, largely jettisoning narrative in favour of vague incident and relentless character study . . . (during this harangue the credits start to roll, music very faint beneath his words) ... In his first film: ‘Cronaca Di Un Areore’ (1950), the couple are brought together by a shared irrational guilt. ‘L’Amico’ followed in 1955, and 1959 saw the first of Antonioni's world-famous trilogy, ‘L’Avventura’ - an acute study of boredom, restlessness and the futilities and agonies of purposeless living. In ‘L’Eclisse’, three years later, this analysis of sentiments is taken up once again. ‘We do not have to know each other to love’, says the heroine, ‘and perhaps we do not have to love...’ The ‘Eclipse’ of the emotions finally casts its shadow when darkness descends on a street corner. (the credits end; voice and picture start to fade)... Signor Antonioni first makes use of colour to underline...Fade to black and then to BBC world symbol

Continuity Voice: And now on BBC another six minutes of Monty Python's Flying Circus.

Dialogue retrieved from Internet site 6 May 2007

<http://www.ibras.dk/montypython/episode29.htm>

The final line in the closing credits of the bizarre, comic satire, Life of Brian, is: “If you have enjoyed this film, why not go and see La Notte”? Nasty little joke.

In the film co-directed by Alain Tanner and Myriam Mézières, Fleurs de sang, [2001], there is a date-rape scene that occurs in a Paris apartment beneath a French oversized, glass-framed poster of L'éclipse, a poster which shows the seduction scene in the apartment of Piero's apartment in L'eclisse.

Another rare, explicit reference to Antonioni is made in Ettore Scola’s C’eravamo tanto amati. Marcia Landy notes that in this latter film--a movie which is replete with cinematic allusions--there are black and white movie stills of Monica Vitti appearing in L'eclisse (see Landy’s Italian Film, p. 362).

Alcott, in a blog (http://www.toddalcott.com/movie-night-with-urbaniak-leclisse.html [accessed 25 September 2012]) on L'eclisse states: “In the closing moments of the movie [L'eclisse], a jet plane flies overhead. The sound-effect geek in me cannot help but note that the ‘jet plane’ sound used is the exact same recording heard a few years later at the beginning of The Beatles’ recording ‘Back in the USSR.’ Coincidence or incredibly-obscure homage? You be the judge.” There is the sound of jet aircraft in the coda of L'eclisse and the beginning of “Back in the USSR,” but I have not independently confirmed Alcott’s assertion that they are identical.

An allusion to L'eclisse is said to also be present in Le Fabuleux destin d’Amélie Poulain (see IMDb [The Internet Movie Database] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0211915/movieconnections Retrieved 19 January 2007). I have carefully looked at Amélie several times--but apparently, not carefully enough--for I cannot find any explicit visual, auditory, or other allusion to L'eclisse in the entire film. (Remarkably, since 19 January 2007, the above IMDb page has been “corrected/revised/updated”; the “Movie Connections” page on the site now says as of 4 March 2007 that “The succession of kisses Amélie gives Nino at the end of the film mirrors the succession of kisses between Alain Delon and Monica Vitti in L'Eclisse.”) I do not find this assertion compelling. Nevertheless, Amélie, the heroine of the film does remark with regard to explicit clips of films we are shown (including a clip from Truffaut’s Jules et Jim) that “Je aime bien les petits détails que personne ne verra jamais.” (“I like noticing details [in films] that no one else will see.”) As the character Amélie utters this remark, a special effect in the cartoon-like pose that Amélie presents itself is inserted by Amélie’s director Jean-Pierre Jeunet: with a red marker pen Jeunet (or if you will, the character, Amélie) circles the small “goof” of an actual insect walking on a pane of glass in the background of a shot from Jules et Jim. The insect literally seems to be walking between the lips of actors Henri Serre (Jim) and Jeanne Moreau (Catherine) who in a two-shot are about to kiss. The insect finally seems to enter screen right into the very mouth of the character played by Moreau. I suspect that the character, Amélie, would like L'eclisse very much, a film that lends itself to an extraordinary degree of flyspecking.

It would be exceedingly liberal on my part to state that Jeunet has placed in Amélie an allusion to L'eclisse that I missed entirely on repeated viewing and did not appreciate even when explicitly brought to my attention by the viewers and critics who contribute to IMDb. The truth is that I do not embrace the view that “The succession of kisses Amelie gives Nino at the end of the film mirrors [in any meaningful manner, ironic or otherwise] the succession of kisses between Alain Delon and Monica Vitti in L'Eclisse.” And yet, the density of allusion in L'eclisse--for example, just the works of art seen in the background of Vittoria or Riccardo’s apartment--is so thick that I assume that I have missed numerous allusions in Antonioni’s film, just as I “missed” or continue to not appreciate the supposed allusion to L'eclisse in Amélie. (Note the paucity of artwork in Piero’s pied-à-terre; he, like Vittoria’s mother, isn’t the type who is interested in doodles of daisies on napkins nor reproductions of modern art on the walls of his apartment.) As an example of how inconspicuous the allusions in L'eclisse may be, consider the shot of the unidentified man exiting a bus near the construction site of the Eur in the coda of the film. Our eyes are drawn to the bold headline of the 10 Settembre 1961 periodical L’Espresso, “LA GARA ATOMICA.” If, however, one zooms in closely at the lower right hand corner of the front page of the newspaper, a reference to the 1961 film, L' Année dernière à Marienbad, is present (this “movie connection” is not listed in the IMDb site page concerning L'eclisse retrieved on 4 March 2007 from:

<http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0056736/movieconnections>).*

Although L'eclisse is not explicitly referred to in the two companion films, Before Sunrise and Before Sunset, both of these latter films have multiple striking similarities to L'eclisse. These similarities, which are so notable, approach being direct allusions to L'eclisse. (Caution!: spoiler warning; plot and/or ending details about films to follow):

1. Before Sunrise concerns a one day “brief encounter” set in Vienna (occurring on June 16, Bloomsday) in which towards the conclusion of the film the couple flirts with the idea of making a vow to never see each other again. Nevertheless, the two would-be lovers finally agree to meet each other again in 6 months at the same Viennese site of their parting, a meeting that neither person will keep.

2. In Before Sunrise, the two main characters pause before a street poster advertising a Seurat exhibition. The character Celine remarks, “I love the way the people seem to be dissolving into the background. It’s like the environment is stronger than the people. These human figures are always transitory.” The film has a morbid concern with death, with the Delpy character visiting a cemetery where the bodies of those drowned in the Danube are interred (reminiscent of the Drunkard drowning in the Eur laghetto).

3. At the conclusion of Before Sunrise, the man and woman do disappear, “dissolve” into the background. However, the “autonomous camera” returns in the final minutes of the film, the “coda,” and makes a photographic inventory of the now empty spots where the two young people had spent the film.

4. The follow-up film, Before Sunset--a kind of Part II--concerns the two characters “accidentally” meeting again 9 years later. Before Sunset could be an alternative title to L'eclisse. Regardless, Before Sunset also ends on an uncertain moment as to whether the man and woman will ever meet again. “Part III” has not yet been made.

The flip side of the question concerns which directors or movies have influenced Antonioni, a question I do not have a ready answer for. (Although, for example, Antonioni’s films have been compared to those of Bresson, I find the comparison weak.) Antonioni, himself, almost never overtly refers to other filmmakers or specific films within the confines of his own movies.

In this note I first asked, “Which filmmakers has Antonioni influenced?” I then asked, “Which filmmakers have influenced Antonioni?” Finally, I now ask, “To what degree are the films of Antonioni self-referential? How much do the films of Antonioni allude to each other? How much has Antonioni influenced Antonioni?” I have already discussed this issue in detail: virtually all of Antonioni’s films concern similar content and style and “refer” back-and-forth to one another. This is not to say, however, that Antonioni is ever “self-referential” in the concrete manner that, for example is evident in Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle in which IMDb (20 April 2007) notes: “In the scene where Juliette drops off her daughter at the day care/brothel, there is a painting on the wall of a screen shot of Nana (Anna Karina) in Vivre Sa Vie.”

(http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0060304/trivia)

I will later discuss the similarities between Hitchcock’s films and those of Antonioni; these similarities do not include a penchant on Antonioni’s part for serial cameo appearances in his films, perhaps the most blatant and intrusive form of self-referencing a film director might enact. In the case of David Lean and Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Lean’s self-interjection into his film was not blatant and intrusive, but modest and discrete; Lean played the microscopic role of the British soldier seen in an extreme long-shot on a motorcycle on the far, western side of the Suez Canal. The Lean character yells across the canal to Lawrence--who is on the eastern bank--what is perhaps the key question of the entire film: “Who are you? Who are you?” (A question that plagues so many of Antonioni’s films, in particular, The Passenger, and the inscrutable girl with no name.) The smallest, most enigmatic smile plays on the lips and in the eyes of the actor, Peter O’Toole. (In Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), the anti-hero of the film played by William Holden has adopted the identity of a dead man, an act that in Antonioni’s The Passenger will drive the entire film.) One wonders, one wishes, that—like the character, Constance, played by Ingrid Bergman in Hitchcock’s Spellbound—that Vittoria had asked Piero just once, “Who are you?” as Constance had asked of the Gregory Peck character, John, in Spellbound. What possible, meaningful, true response could Piero have ever given to such a question from Vittoria? As already mentioned, Antonioni is not interested in the opposite of “suspending disbelief”: i.e., promoting the realization that a film is artifice, as in, for example, meta-cinema such as 8½ and its reminder to the audience that we are witnessing the production of a fiction. Antonioni does not usually engage, like Velázquez and “Las Meninas,” in the ordinary sense of “mise en abîme” (unless, one considers that L’eclisse is itself, utterly and completely, the abyss). However threadbare are the stories of Antonioni’s films, Antonioni is ultimately a quite conservative and traditional storyteller, adhering to a realist aesthetic (See Endnote #39).*

There are, however, at least 3 published “screenplays” of L'eclisse, all of which differ to some degree from each other, as well as from the completed film. (Vide infra, Endnote #8 for further information regarding the definitions of “screenplay,” “script,” “shooting script,” “cutting continuity,” and “release dialogue transcript.”) The “original” screenplay in Italian is contained in Lane’s 1962 book, L'eclisse di Michelangelo Antonioni. This treatment both contains scenes that do not appear in any version of the final film as well as omits some scenes or dialogue that do appear in the film. The two other screenplay versions--the 1963 Orion Press version in English and the 1964 Italian Einaudi version alluded to above--resemble each other more than they do the original 1962 version contained in Lane. (Lane on p. 22 of his book also alludes to “bloc-notes” regarding L'eclisse contained in drawers in Antonioni’s apartment that I do not believe are presently available or have ever been published.) A transcription of the actual dialogue from the film itself (a “release dialogue transcript”) in both Italian as well as an accompanying French translation has been published recently in L’Avant-Scène Cinéma, Février 1993. n° 419. To my knowledge, no direct transcription in English translation of the dialogue in any version of the completed film has ever been done. It is noteworthy that all of the screenplays are quite “sketchy” in terms of many of the rich detail that characterize the completed film. For example, many indications regarding shot composition or specific production details (such as Piero’s magnifying glass) are not indicated in any of the screenplays. I know few of the specifics as to how Antonioni actually shot his incredibly detailed film. Lane in his diary of the shooting of L'eclisse writes:

Gianni di Venanzo, director of photography of The Eclipse, never knows what camera set-up Antonioni wants until they come to the scene. The script-girl will not know until the scene has been shot and the ‘shooting script’ is written as the film proceeds (not just modified as in most films). Shooting a scene near the lake when Piero and Vittoria are walking, I noticed how, when one shot is completed, everyone leaves Antonioni alone. It is taboo to go near him as he meditates on how he wants the next set-up. When he is ready, he calls Di Venanzo and Indovina over and explains what he wants.

There seems, therefore, to have been an off-hand, improvisational quality to the making of L'eclisse that contradicts what I had originally assumed was an extraordinary degree of thought and attention to detail that proceeded the actual shooting of the film. Lane writes that the “screenplay” for L'eclisse was written in only 15 days in the first half of July, 1961, only days before principal photography of the film was to begin on July 20. Lane adds that an original “story”(“racconto”) was never put to paper. (Bernardini writes on p. 189 of his book that “Il soggetto vero e proprio non è mai stato scritto.” / “A proper treatment was never written.”) A seminal moment in the conception of L’eclisse occurred in February of 1961 at which time Antonioni was filming a real eclipse of the Sun in Florence.* Incorrectly, I had formally suspected that Antonioni approximated Hitchcock in the sense that the latter’s films were essentially “shot” even before the camera ever began rolling. For Hitchcock, the actual shooting of his carefully composed films was a kind of afterthought. Detailed storyboards outlining in great detail the composition of individual shots and scenes were employed by Hitchcock. This is no different from the elaborate preliminary work that many artists employ before placing brush to final canvas. Standing opposed to my assumption regarding how much preparation may have occurred before principal photography began are Antonioni’s own words. In an interview he gave for Cahiers du cinéma in October of 1960 (excerpted in Leprohon’s book, Michelangelo Antonioni, An Introduction), Antonioni stated that “Isn’t it during the shooting that the final version of the scenario is arrived at? . . . No one can fail to see that the shooting script has become less detailed than it was formerly. . . Sometimes I arrive at the place where the work is to be done and I do not even know what I am going to shoot. This is the system I prefer: to arrive at the moment when shooting is about to begin, absolutely unprepared, virgin.”

Not only are there several different screenplays of L'eclisse, there are also several different final versions of the film. Ted Perry in his Guide to references and resources has written that “Against Antonioni’s wishes, the Hakim brothers (the producers of L'eclisse) cut 14 shots out of the closing sequence of the film. The U.S. distributor, according to several reports, made further cuts in this section.” (p. 109). As I have already remarked in a footnote of chapter III (“being viewed in reverse”) of this book, Jonathan Rosenbaum has written that some U.S. distributors lopped off the entire coda of L'eclisse. If I were compelled to choose between eliminating the coda or all of L'eclisse up to the point of the coda, I would choose the latter.

There is a possible explanation as to why so little preparation seems to have preceded the making of so intricate a film. The concepts, the themes, the world view embodied by L'eclisse may have been so grounded in Antonioni’s mind that a specific detailed script was largely unnecessary. Antonioni knew what he wanted to “say” within the broad outlines of a relatively simple plot already in place. By some collision of nature, nurture, and providence, Antonioni was that rare director who could paint the storybook of his film on the screen of his mind. Given so “pre-determined” a sense of his film, so complete an understanding of the building blocks of L'eclisse--its themes--Antonioni could improvise, play with his characters or concepts with remarkable liberty. Whether it rained or shined, whether the exigencies of shooting meant he couldn’t do this or that at a particular moment at a particular place, Antonioni could still only create a film that would look like L'eclisse. The film might have been shot in 10,000 different ways and still remain entirely the same.

Mancini and Perrella (p. 410) write:

The various versions of the script, the shooting schedule, and its variations, the choice of locations, the sketches of the settings and costumes, the screen-tests, the estimates, the various work schedules, the agendas, and then the unused material, the cuts, the reserve material, the editing copies, the censorship cuts, the dubbing and the various editions are only some of the material which is lost and which every archaeologist should try to conserve and catalogue.

Mancini and Perrella conclude, as if they were true sons of Antonioni: “This material is fatally destined to be lost, and not even a scrupulously conservative director like Antonioni can avoid this.”

As the curtain in Riccardo’s apartment is drawn and the “Fungo” revealed, the structure appears other-worldly. Indeed, unless one is familiar with the Eur, a reasonable question that arises upon first seeing the water tower is, “What the hell is that?” Furthermore, in later shots of the tower, Antonioni gives us no further information that allows us to clarify its identity.

The opening shot of Ozu’s 1960 film, Late Autumn, is a view of the massive Tokyo Tower. As is the case with the Fungo in L’eclisse, if one is unfamiliar with Tokyo and its tower, the appearance of the structure in Ozu’s film is potentially startling. One may ask oneself, again, “What the hell is that?” In the case of Ozu, it is quite likely that he is opening his film with a view of the Tokyo Tower to present a kind of establishing shot to his predominantly Japanese audience who will be expected to be quite familiar with the famous tower (“Just as the Eiffel Tower is used in cinema to immediately locate a scene in Paris, Tokyo Tower is often used in anime and manga, especially if the anime or manga is set in Tokyo’s Azabu-Jūban district, or because it is produced by TV Asahi, which uses the Tower as a transmitting tower.”)

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokyo_Tower> retrieved 30 October 2007.

I think it less likely that Antonioni is presenting the Fungo to our eyes in order to establish for either an Italian or international audience that L’eclisse is set in the Eur quarter of Rome. Contrariwise, I suspect that Antonioni’s focusing on the Fungo has both a primarily aesthetic and intellectual basis. (Already commented on above is Antonioni’s presentation of il fungo in multiple guises of atomic mushroom cloud, silvery dome of atomic reactor, and glans penis.) Nevertheless, both Ozu and Antonioni do share in common an interest in architecture and the presentation of the cinematographic image in a painterly manner. Ozu’s films are replete with contemplative static long takes of buildings.

From Antonioni’s earliest documentaries such as La villa dei mostri, he is fond of populating his films with unusual buildings, an obvious concern with architecture in general that permeates his œuvre. Examples include the Villa Palagonia in Bagheria, Sicilia, with its “Salone degli Specchi” (“Hall of Mirrors”) where the Sicilian fisherman are interrogated early in L’avventura. (Antonioni “transforms” the Villa into a police station.) La Notte opens with an unusual tracking shot filmed from an elevator descending from the then tallest skyscraper in Italy, the Pirelli Building (il “Pirellone”) of Milano. Il deserto rosso is replete with adoring and unusual perspectives of chemical factories near Ravenna, as well as the bizarre appearing series of radio telescopes of nearby Medicina, Italia. Much of Chung Kuo Cina concerns exotic Chinese architecture. In The Passenger we have the unusual architecture of Gaudí, particularly the Palau Güell and La Pedrera of Barcelona. Zabriskie Point terminates at the Hovgaard House in Carefree, Arizona, a perfectly named place for the Apocalypse to occur. (No, the house wasn’t really blown up, but an expensive, full-scale mock-up near the original house.) In Al di là delle nuvole, there is the unique Palazzo dei Diamanti in Antonioni’s hometown of Ferrara, as well as the striking portico, the Loggiato dei Cappuccini at the Santuario di Santa Maria in Aula Regia of Comacchio, which resembles an unidentified church, piazza, and portico in a town of the Po River delta which I have been unable to precisely identify (Comune di Pontecchio Polesine? See: http://www.polesinefilmcommission.it/storia.html [accessed 24 July 2012]) in Antonioni’s first major documentary, considered by many to be his first film, Gente del Po [1947]. A plaza and church at its base are explicitly referred to but not mentioned specifically by name in the screenplay of Gente del Po in Il primo Antonioni. (“Il Po . . . appartiene al paesaggio della mia infanzia. Il Po a quello della mia giovinezza . . . La sua forza, il suo mistero. Appena mi fu possibile tornai in quei luoghi con una macchina da presa. Così è nato Gente del Po. Tutto quello che ho fatto dopo, buono o cattivo che sia, parte da lì”. / “The Po is the land of my infancy. The Po has that of my youth . . . Its power, its mystery. As soon as it was possible I returned to this land with a movie camera. Thus was born Gente del Po. Everything that I did afterward, whether good or bad, comes from there.” Michelangelo Antonioni tratto da “Dei paesi tuoi,” intervista di Ennio Cavalli. Thus, was Gente del Po the alpha and the omega of Antonioni’s film career . . . and life. See also Internet site: “Provincia di Ferrara, terra e cinema, land and cinema” <http://www.emiliaromagnaturismo.it/it/pubblicazioni/download/Pubblicazioni_Misc/GuidaCineturismo.pdf> [accessed 21 July 2012; in Italian and English].) The principal characters of Antonioni’s segment of Eros--a characteristically troubled couple--reside in of all places, at the lakeside Torre di Burano in Capalbio (quite close to where Antonioni had shot La villa dei mostri in Bomarzo over 50 years earlier.)

This aesthetic interest in architecture dovetails with a movie making side to Antonioni that is often overlooked: his engineering-like interest in technological invention which is particularly prominent in Zabriskie Point (with the revolutionary “high speed/slow motion” cinematography of the destruction of the Hovgaard House and its contents), The Mystery of Oberwald (a film in which Antonioni seemed more interested in the video manipulation of colour than the movie itself), and the magisterial ending of The Passenger in which Antonioni used multiple gyroscopes and an approximately 30 meter crane to film a shot that would have been technically much easier with a Steadicam (the “modern” Steadicam invented shortly after Antonioni had finished The Passenger). For Antonioni, cinema was as if a child’s toy box, not dissimilar to the enthusiasm he displayed with puppetry as a child, perhaps not entirely dissimilar to the science and engineering toys that Giuliana’s son, Max, plays with in Il deserto rosso. As Antonioni emphasized when discussing Red Desert, he is not opposed to factories, industrialization, or advancing technology. Instead, one might say that Antonioni is consumed by the aesthetics of technology. In a filmed interview which Antonioni gave--contained within the documentary by Sandro Lai, Michelangelo Antonioni: The Eye That Changed Cinema, a documentary which in turn is included as a supplement in the Criterion Collection DVD of L’eclisse--Antonioni speaks with almost breathless admiration of new computer technology employed by Spielberg and Lucas which Antonioni states he feels will someday not only revolutionize cinematography, but the way we regard life itself.

So important is this ostensibly unimportant intersection that Antonioni takes us there three times in L'eclisse, the last time at the very conclusion of the film. It is the very banality of this spot, its seeming unimportance that makes “ground zero” so much more than nowhere or nothing. There is, in short, a world contained within the water barrel. The third time is not, however, charmed: Vittoria, Piero, and ourselves have an appointment at eight o’clock, but as Sitney has written, it is we the audience whom are stood up. (The last time I saw L'eclisse at a cinema the thought occurred to me that I should walk out of the theater when Vittoria and Piero last embrace and promise to meet each other again at eight, and like the American distributors of the film, amputate the pain of L'eclisse’s coda.)

José Moure in his study of Antonioni notes that half-finished structures are a recurrent motif in Antonioni’s films. In addition to the half-finished apartment building in the Eur of L'eclisse, Moure also cites the “perpétuel chantier” of the house in La signora senza camelie, Clelia’s boutique in Le amiche, and Giuliana’s store-in-progress in Il deserto rosso. Moure also refers to L'eclisse and the stairwell in the office building of Piero, the elevator shaft of which is apparently undergoing some kind of repair or restoration. Moure writes of Antonioni’s abiding interest in stairs and stairways and of Antonioni’s abandoned project of 1950 entitled Scale (Stairs), in which the director had wished to film a succession of brief incidents occurring on different types of staircases. Moure writes (p. 19):

[Antonioni] a fait de ‘l’escalier’ un de ses espaces scénographiques et architecturaux privilégiés : un lieu symbolique, intermédiaire et vertigineux, qui travaille l’inconscient des personnages et de la fiction ; une parenthèse spatiale où, en supsension et entre deux endroits, les actions se nouent et se dénouent, les êtres se croisent, se rejoignent, se séparent, s’épient, se révèlent, s’abandonnent au vide ; un espace-limite où les consciences expérimentent le vertige de la faute et de l’égarement, les corps celui de la chute et de la mort, les regards celui de la disparition et de la perte.

[Antonioni] chooses “the stairway” as a favored and privileged architectural site: a symbolic place, intermediate and vertiginous, where the subconscious of his characters operates; a spatial parenthesis where suspended between two places, the actions of his characters form and become undone, beings encounter one another to form a union and then separate, spy upon each other, reveal themselves and then abandon themselves to the void; a place where people experience the vertigo of error and displacement, where the body undergoes a fall and a death, where our gaze discerns disappearance and loss.

One remembers in particular the importance of the stairway and elevator shaft in Antonioni’s first feature film, Cronaca di un amore, the site of a literal death, around which the plot of the entire film is spun. Nor can we forget Antonioni’s fixation on a spiral staircase in his last major film before his stroke, Identificazione di una donna, an image which Chatman chose as the emblematic cover for his major work on Antonioni, Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World (Of all of the images ever taken by Antonioni, Chatman and Duncan chose an image of Vittoria and Piero--a still from L’eclisse--of Vittoria and Piero’s faces side-by-side in extreme close-up, as the cover for their 2004 book, Michelangelo Antonioni. The Investigation. [“The Complete Films”]).

In 1950, Antonioni made a 10-minute documentary, La funivia del Faloria, concerning the gondola (“tram”) that runs from Monte Faloria to Cortina d'Ampezzo. Cameras were mounted perilously on the tops of these cable cars, a cinematographic feat that prepared Antonioni for a similar maneuver above the Barcelona harbour in The Passenger a quarter century later. A restoration of this early documentary was recently done by the Associazione Philip Morris Progetto Cinema in which the short was cut to 4-minutes and renamed in Italy, Vertigine . . . “Vertigo.”

This omen, that of Vittoria separating the wood from the matches, is but one example of the larger phenomenon of adumbration-foreshadowing that characterizes all of L'eclisse which I discuss in Chapter 3, The Shape of Things to Come.* There is the sense that L'eclisse not only begins at the end, but that the film is over before it has even begun. So many dark signposts litter even the earliest moments of the film (e.g., Vittoria and Piero meet in the sepulchral Borsa at the moment when the death of a salesman is announced) that in hindsight one can bemoan that Vittoria and Piero never had a chance. The film becomes a 2-hour exercise in the loss of a love never truly possessed, the obsequies held at love’s threshold. Although in the first sentence of this book I write that “L’eclisse begins at the end,” the movie and its would-be lovers may be said to have ended even before it began, flaming out as matches and a piece of wood fall from the sky to drown in the dirty water of a barrel at a tumble-down, all-fall-down construction site.

A similar little Antonionian moment--one that should have alerted us to doom ahoy if we have come to know Antonioni at all--occurs at the beginning of L'avventura. I am not referring to the very opening scene of this latter film when Anna’s father explicitly warns his daughter that Sandro will never marry her. (This warning isn’t a little gloomy signpost that one might overlook, but a warning flare in the night.) Nor am I referring to the overt despair and depression that characterizes Anna as she drives with her friend, Claudia, to Sandro’s apartment on the Isola Tiberina. Something smaller happens, a little utterance by Claudia that implies that things are finished before they have begun: Anna, after not seeing Sandro for a month, stalls after arriving in front of the apartment. She doesn't want to rush into the apartment into the arms of the man that both logic and the heart would suggest she should run towards. Claudia immediately sees trouble ahead and mutters with small world-weary regret, “Eh, va bene. Addio, crociera.” (“Oh well, all right then, so long, cruise.”) In a deeply profound way, Claudia is not only sighing, “Goodbye, love,” but “Goodbye, film. Goodbye, L'avventura.”

Only seconds after Claudia rings the death bell of the film, “Addio, crociera,” Anna enters the front door of Sandro’s apartment, ascends the stairs, soon takes off her clothing, and--in the most desultory of manners--makes love with Sandro. Yes, this is discourteous to Claudia, who is waiting in the street outside Sandro’s apartment. But it is a kind of tacky discourtesy that conceals a deeper, more tragic disregard for both friendship and love. Inexplicably, the front door of Sandro’s apartment is wide open. Claudia enters the foyer, pauses for a moment and exits, so very deliberately shutting the door. Claudia’s act of shutting the door is but another “addio,” as if a stage curtain had unexpectedly fallen not at the end of a play, but at its beginning. Anna and Sandro are finished . . . as is--in some profound way--the film itself. But the film trudges on, and towards its conclusion Sandro is now in a room with his new lover, Claudia, in the Hotel Trinacria in the heart of historic Noto, making love to the substitute for Anna, Claudia, in a manner that could meet the legal definition of rape. So very unhappy, so very unfulfilled, Sandro, a man who has failed to meet the dream of his youth to be a great architect, stands at the hotel room’s window fronting Corso Vittorio Emanuele III, the architectural splendor of the jewel of the Spanish Baroque of Sicily before him. And Sandro, as Claudia had done previously in Rome with Sandro’s very apartment door, closes the shutter, bringing down, yet again, the curtain on life before him.

Ted Perry on p. 62 of his Guide to References and Resources concerning Antonioni, quotes from the screenplay of Antonioni’s 1949 short documentary Superstizione (which in turn is published in Carlo Di Carlo’s Il primo Antonioni). In this documentary the narrator describes a superstition said to bring good luck: “. . . you should throw a penny, a feather, scissors, one piece of iron and one of wood into a pail of water.” Vittoria may be performing just such a rite. Vittoria’s mother, an overtly superstitious person, performs her own rituals in Rome’s Borsa, scattering salt, for example, on the Borsa’s floor.

The piece of wood and matches thrown into the water barrel of L'eclisse are also anticipated by another piece of wood and matches that appear in Le amiche. During the beach scene of this latter film, Rosetta is shown standing alone on the beach, her attention focused on a relatively small nondescript wooden crate floating, not in the water barrel of the Eur, but in the surf of the Ligurian Sea before her (a typical example of the distractability of Antonioni’s characters, their attention often drawn to seemingly unimportant and discrepant objects). Nearby, Lorenzo, a failed artist (played by the actor, Gabriele Ferzetti, who will later play the failed architect of L’avventura), sits on the same beach doodling on the inside cover of a book of matches. Antonioni shows us an insert shot of Lorenzo’s doodle, the sketch of a woman’s head, that of Rosetta.

The scene concerning the second meeting between Vittoria and Piero at the construction site is a marvel of understated choreography, an ostensibly banal encounter whose small movements and pedestrian comments are charged with meaning. Piero nonchalantly throws the empty matchbook into the water barrel. The next shot is a close up of the barrel in which we see that the matchbook has lodged underneath the piece of wood that Vittoria had previously thrown into the barrel. The matchbook lies in such a manner that it is folded open with its outside cover lying face down in the water. (It is only later in the coda of L'eclisse that we again see the matchbook floating in the barrel, this time with its cover mysteriously upright, a scene containing two Italian cypresses.) In the corner of the shot is Vittoria’s hand resting on the barrel’s rim. The hand moves, and touching only the wood and water, separates wood from matchbox. The camera then recedes to show Vittoria as she moves to screen left and turns around placing her back to the barrel as if to hide the act she has just performed. Piero is apparently oblivious or disinterested as to why Vittoria would stick her hand in the dirty barrel to push the broken stick away from the matchbook. In the background an unidentified woman darts past. Piero asks Vittoria how she is doing (“Come stai?”) to which she replies in Italian, “Bene,” the English subtitle being “Fine,” a kind of accidental homonym indicating “well” in English and “The End” in Italian. Piero informs Vittoria that he has bought a new car, a BMW. Vittoria does not seem happy upon hearing this news, and turns her back to the camera. The shot is now broken as the camera films Vittoria and Piero from a new angle 180 degrees from that of the preceding shot. Piero then asks Vittoria whether they should go somewhere, suggesting, “casa mia” (“my place”), to which she agrees, yes, “casa tua.” (They go not to Piero’s place, but instead, to the funereal apartment of Pietro’s parents at Piazza Campitelli.) A look of concern and foreboding persists on Vittoria’s face. There can be little doubt that by accepting Piero’s invitation she is agreeing to soon make love with him “at his place.” Vittoria appears to accept his invitation in a rather defeated manner, her bearing suggesting a kind of resignation or capitulation to the inevitable, an “all right, let’s get it over with” attitude. (Shortly thereafter, in the apartment of Piero’s parents, when Piero tears her dress--or the dress tears itself--Vittoria retreats alone into the bedroom where she takes off her necklace and then begins to take off her dress, confirming that she fully anticipates and intends to cooperate with what she knows will be an imminent seduction. Indeed, who is seducing whom?)

After agreeing to go to Piero’s “place,” Vittoria and Piero then turn around and head off to cross the street just as a priest and an unidentified man are seen walking together in the background. The scene has taken place at the water barrel beneath a large sign that is just off screen above Vittoria and Piero’s heads. (We will see the sign again when the old man of the coda moves off screen, his head having previously obscured the sign, the words of which are still difficult, if not impossible, to decipher.)

A not so obvious, seemingly unimportant question is why Piero would throw the matchbook into the barrel in the first place? One discards matchbooks when they are empty. No more matches. No more Alfa Giulietta Spyder. Soon, no more water in the barrel. And in the end, no more Vittoria and Piero.

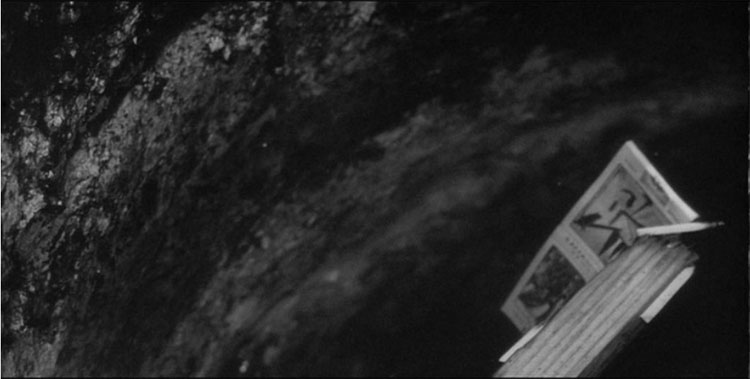

A final mystery among other final mysteries is how, if the matches initially fall with their cover face-down, do the matches later appear face-up at the end of the film? A simple answer would be that this is an error in cinematic continuity, a technical oversight that may have occurred over hours or days of shooting with the production crew continuously trying to maintain perfect, seamless continuity, and failing. In a lesser film where large issues don’t matter, let alone small issues such as why a matchbook has flipped, such errors are meaningless. If, however, one is a filmmaker attempting to make a movie in which everything counts, then accidents--whether careless or not--become hazardous; the temptation in interpreting such a film that strives for obsessive attention to detail is to attribute meaning to what may be merely a technical glitch with no meaning at all. In Ulysses, a very obsessive work of art, “the man in the ‘mackintosh’ ” is spelled in several different ways; is this due to the fault of French typesetters in Paris who didn’t speak English, or was this deliberate on Joyce’s part—“intentional errata”—a small clue that may point to the path leading to enlightenment?* (As Stephen Dedalus remarks in Ulysses (the corrected text [342]): “A man of genius makes no mistakes; his errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.”) Another answer would be that the matchbook, like the gate through which Marta’s dog escapes, or Vittoria’s torn dress, has a life of its own, enjoying an attribute usually ascribed to living things, that of animation. A less mystical solution, however, presents itself. After Vittoria separates the matchbook from the piece of wood when she and Piero meet for the second time at the barrel, it is not until the end of the film in shot 4 of the coda (Criterion Edition [DVD] of L'eclisse, with shot 1 of the coda being that of the nursemaid and carriage with a panorama of the Eur in the background as an establishing shot) that we again clearly see the matchbook, this time with its cover face up revealing the two Italian cypresses. In the coda of L'eclisse there are three distinct shots of the inside of the barrel. In the first such insert shot of the barrel--shot 4 referred to above--we clearly see the matchbook, “cover face-up,” slowly circling counterclockwise. The piece of wood is less prominently seen to screen right of the matchbook, neither wood nor book touching one another. The water in the barrel appears to be slowly circling (the barrel--somehow punctured--leaking water from its first presentation on stage from an exterior perspective in shot 3 of the coda).

It is not until shot 19 of the coda that we again see the interior of the barrel. We clearly see both matchbook and piece of wood, again neither object touching. Both objects continue to slowly circle clockwise on the surface of the barrel’s water perhaps due to the smallest degree to the Coriolis effect. We now more clearly see and hear the rupture of the barrel. (In the subsequent shot 20 the camera follows the rivulet of water, a miniature Tevere or Zambesi River, as it falls off the curb into the nearby gutter, Vittoria Falls. At the edge of the sidewalk, lies a small piece of paper which presumably, if turned over, would reveal a drawing of daisies.)

Shot 39 of the coda is the last time we shall see the interior of the barrel. The piece of wood and matchbook are no longer separated, but are again touching, “interlocked” as they continue to swirl ever faster. The two objects, once deliberately separated by Vittoria, are now reunited even as Vittoria and Piero are now themselves undone. Now, for the first time we see what appears to be two, perhaps three match sticks, perhaps spent, also adjoined to the piece of wood and matchbook. (It would be “nicer” if there were but two spent matchsticks, the analogy to Vittoria and Piero thus striking.) The matchbook is seen slowly tumbling end-over-end along its long axis as it is swept in the circling current caused by the water flowing out of the ruptured barrel. It is perhaps this rupture, in turn caused by the unseen hand of Antonioni, that permitted the matchbook to flip over, revealing the image of a miniature, arboreal world.

Shot 39 of the Coda

I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space . . .

It may be surprising that the matchbook and piece of wood are still even floating on the surface of the water in the barrel at all. By the time L'eclisse arrives at its coda, it is unclear how much time has elapsed since these two things were thrown by Vittoria and Piero respectively in the barrel, days or even weeks ago. Why the matchsticks now appear suddenly on the scene is also unclear.

Angelo Restivo in the context of Blow-Up writes in a Lacanian vein of the significance of the “partial or lost object.” He includes among such objects the propeller that is bought in the antique store in Charlton, the once precious neck of the broken guitar left lying like discarded junk on Regent Street, and the placard, “Go Away!” that follows its own instructions as it blows away from the back seat of the Photographer’s Rolls Royce Silver Cloud as he races away from the “demonstrators” in London. Restivo states that in Lacanian theory that when a thing is wrested out of its context, “the sublime object becomes the ‘gift of shit.’ ” Writing of Viaggio in Italia, Restivo continues to refer to such waste as “scraps of the Real, points at which meaning is occluded and the image becomes mysterious. Retroactively, these scraps acquire meaning through the process of metaphor, but only after a traumatic encounter with the Real. . . .” Although Restivo writes at some length of L'eclisse, he does not refer to those ultimate scraps of Roman “bricolage,” the broken piece of wood and book of matches discarded in the water barrel of the Eur. The objective--or to employ language more appropriate to the context of L'eclisse--the market value of the wood and matches is zero. They are also aesthetically worthless. And yet, subjectively, such scraps are “sublime,” gold itself, glittering objects that are literally destined to spiral down a nearby Roman gutter to join the excrement of several million Romans on a voyage in an ancient sewer system, the cloaca maxima, to the sea. In the dream iconography of Freud, gold is, of course, shit.

Although all three principal “screenplay” versions of L'eclisse (1962 Lane, 1963 Orion, 1964 Einaudi) as well as the English sub-title in the Criterion version indicate “un libro” (“a book”), in the film itself Vittoria seems, perhaps, to actually utter the word, “dito” (finger). The issue is further muddled by the “fourth” screenplay of L'eclisse published in February 1993 in L’Avant-Scène Cinéma, n° 419, an Italian transcript that is taken directly from the film and then also translated into French. This latter screenplay indicates that the Italian word spoken by Vittoria is “dito,” but translates this word in French as “livre” (“book”)! If the confusion regarding Vittoria’s fundamental declaration is not yet sufficiently addled, David Giametti, in his 1999 study in Italian of Antonioni (p. 99), simply eliminates the third of the four items in Vittoria’s list. A recent German study of Antonioni by Müller eliminates the second element and introduces a new verb, “(die Zeit) vertreiben”: (“Es gibt Tage, da ist es mir gleich, ob ich mir mit Stück Stoff, einem Buch oder einem Mann die Zeit vertreibe.” / “There are days in which passsing time with a piece of cloth, a book, or a man are alike to me.”) On the other hand, the 1963 Orion English translation adds a fifth item, that of “thread” (p. 296). Debora Farina, in her 2005 book written in Italian, Eros is Sick, hears Vittoria’s vital declaration in a uniquely original manner: “Ci sono giorni in cui una sedia, un tavolo, un libro, un uomo sembrano più o meno la stessa cosa.” / “There are days in which a chair, a table, a book, a man seem more or less the same thing.” (Italics added by author, dsr.) One would not think that this utterance of Vittoria could be repeated and translated in so many different ways by so many different people. If we cannot even agree on what Vittoria says, how can we begin to understand what is the meaning of her utterance or why she says it? Perhaps Vittoria’s pronouncement may be heard as a kind mysterious aphorism, a sutra (which in Sanskrit may be translated as a “rope” or “thread”) which ties discrepant objects together? The moral—if there is one—is not that we should not trust sub-titles or translations, but that we should wonder if any of the words any of us actually utter come unembroidered directly from the unadorned heart.

And what of the minute of silence for the death of a salesman? What was the salesman’s name? Müller in his 2004 book on Antonioni’s films states that the dead man’s name was “Vittorio Domenico” (p. 105). Müller evidently believes that it is significant that the dead salesman bears the masculine variant of Vittoria’s name (“Der Verstorbene ist namensverwandt mit Vittoria gewesen: Er hieß Vittorio.” [p. 113]). L’Avant-Scène Cinéma (1993) transcribes the name, “Di Strozzi Domenico,” directly from the dialogue of the film. But, inexplicably, in L’Avant-Scène Cinéma the French translation of the Italian--the two translations lying side by side on p. 29--identifies the dead man as “Domenico Vitrotti.” Three other “screenplays”--from Sei film (Einaudi editore), Lane’s L'eclisse (Capelli editore), and Screenplays of Michelangelo Antonioni (Orion Press)--all identify the dead broker as “Vitrotti Domenico.” (Presumably, as is the Italian custom, Vitrotti is the surname.) Who then was the dead man? Has the Borsa become the tomb of the unknown stockbroker, nomen nescio, ignoto, known only unto God? As in the case of The Passenger has an exchange of bodies occurred? Should the body, if it ever existed, be exhumed for proper identification? All of this, of course, fits neatly with the abiding Antonionian concern with the fluidity or fragility of identity. The Writ of Habeas Corpus has been suspended in both the Borsa of Rome as well as a dusty hotel room in Chad where the identity of a dead man is in question.

The issue of how we look at and regard things is, of course, an abiding concern of Antonioni, one that concerns in particular his films, Il deserto rosso and Blow-Up. (I shall discuss later in a different context the more general issue of misperception chez Antonioni. Misperception in an Antonioni film may be auditory as well, the mirage heard as well as seen [vide infra, note 12].) As in all works of art, there may be as many perceptions of L'eclisse--read “interpretations”--as there are viewers of the film. How we perceive a film by Antonioni becomes not merely a psychological issue, but one with an epistemological and ultimately ethical dimension. Antonioni is constantly engaging us with the question, “Is there more here than meets the eye?”

S. Staggs writes, “The terms ‘script,’ ‘screenplay,’ and ‘shooting script’ mean more of less the same: a blueprint used first by art director, costume designer, and other specialized technicians, then by directors and actors. If you read a published ‘screenplay’ or ‘script’ you’re reading something different from the actual dialogue you hear from the screen. That’s because changes are made every day during filming--by producer, writers, director, or actors. The only way to read the exact words spoken by actors in a film is from the ‘release dialogue transcript,’ a stenographic record of every utterance. (The term ‘cutting continuity’ is sometimes also used to mean not only the dialogue as heard on screen but a precise written description of shots, camera angles, and the like.)” L’Avant-Scène Cinéma is to my knowledge the only document that approximates a release dialogue transcript or cutting continuity. It is peculiar, however, insofar as the Italian dialogue adheres closely or is identical to that of the film, but the translation of the Italian dialogue into French--as noted above--is occasionally faulty. Indeed, the French dialogue may actually quote lines never spoken by the actors. For example, on p. 72 of the L’Avant-Scène Cinéma issue, the Italian dialogue is transcribed correctly, but the French translation inexplicably adds important words never uttered by the actors: In this particular example, the French dialogue has Piero asking the Bestiola to meet him at “10 heures 10.30 heures et demi,” something Piero never says in the original Italian audio version of L'eclisse. This is a doubly peculiar error in that Piero is arranging an evening assignation, one that would occur at “20 heures 20.30 heures et demi.” This is an especially grievous error in light of the vital importance the precise hour of 20.00 casts in L'eclisse. L’Avant-Scène Cinéma does not indicate which “version” of L'eclisse was used, e.g. the original Italian audio version, or perhaps a French dubbed version, or any version with possibly incorrect French sub-titles

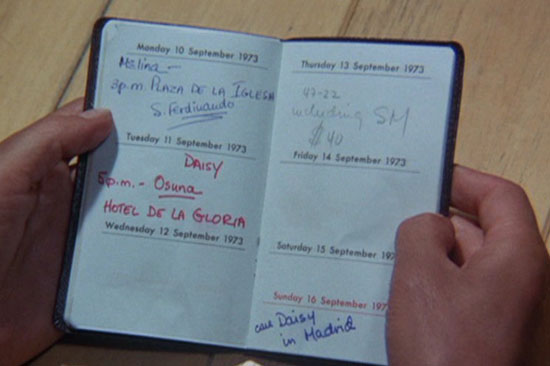

I suspect that Antonioni deliberately placed these trees as props, or altered them in some way. Biarese and Tassone (p. 75) write that while directing the French episode of I vinti in the woods of Varennes, Antonioni both cut down some trees as well as planted new trees. Antonioni made similar dramatic alterations in both the landscape and cityscape of his other films, in particular, Il deserto rosso and Blow-Up. Assheton Gorton, the art director of Blow-Up has said, “We must have painted half of London black, to neutralize and emphasize certain shapes. Antonioni wanted to take a whole row of anonymous, grey London houses (about a 300-yard stretch) and paint them all white. That is, London is not always London. The London we see is the London we make.” (Wood, Gaby. Internet article. Guardian online, 2/14/99). In a March, 1961 appearance at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia Antonioni specifically stated that it was sometimes necessary to alter a “natural” setting by “adding trees.” A preoccupation with trees, particularly pairs of trees, is evident in films by Antonioni antedating L'eclisse (and will reappear in later films such as Blow-Up). In La notte, Lidia and Giovanni walk through an arch flanked by two Italian cypresses in the scene near the Breda factory on the outskirts of Milan. Later, in the final scene of La notte, the doomed couple stop momentarily beside two trees near the sand trap of the golf course. Minutes later in almost the last image of the film, Antonioni captures Giovanni desperately trying to make love to a reluctant Lidia while both are lying in the pit. Behind them are the same two trees filmed from a perspective 180 degrees removed from the original shot of the couple standing aside the trees. According to an Internet site (“The Complete Rod Taylor Site; http://www.rodtaylorsite.com/zabriskiepoint.shtml [retrieved 13 April 2006]), Antonioni chose the Beneficial Plaza Building at 3700 Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles as the headquarters for the businessman-character, Lee Allen, played by Taylor, “because of its facade and architecture based on the Italian renaissance. But because it didn’t look like Los Angeles, Antonioni added palm trees.” (As the Allen character is seen walking in the lobby of the building he momentarily stops before a large electronic display board of the stock market quite reminiscent of the big electronic board that hovers above the Roman Borsa, both these boards vaguely reminiscent of the “Big Board” in the war room seen in Dr. Strangelove, as well as the ultimate motion picture screen of the Strategic Air Command Center showing bombers containing hydrogen bombs hovering like vultures above their “fail safe” points in Sidney Lumet’s movie of the same name)* (Karen Pincus, writing of L’eclisse, notes that the “prices of the azioni (stocks) appear on a large board, changed by a flipping mechanism that causes a momentary eclipse”). In the final moments of The Passenger, Antonioni’s “autonomous” camera fixates on an undistinguished landscape painting hanging above the altar of Locke’s bed in the Hotel de la Gloria. The foreground of the painting is dominated by two trees joined at their base aside a lake, a building resembling a monastery visible in the background.

If one follows the lead of the Photographer of Blow-Up, and carefully examines a still of the two trees of L'eclisse, one clearly sees oblique supports holding them both up. (It is unclear whether these two trees were actually “propped” up by Antonioni; such struts are also visible supporting a tree near the musical flagpoles that Vittoria encounters on the African night of searching for Marta’s dog. Complicating matters further with regard to ostensibly summer trees that are leafless, note that although L'eclisse is set in the period June-September, filming began on 20 July 1961 and continued into October, the autumn of the same year. Additionally, I am uncertain as to the kind of tree Antonioni employed, whether acacia, willow, or other.)

Chatman has written that “The particular kind of interpretation demanded by the tetralogy is that which uncovers significance in the minutiae of appearance.” Or as Brunette has written, “(Antonioni’s films) seem self-consciously to present such a plethora of particular, irreconcilable textual details that critics are unable to escape a confrontation with the fact, the procedures, and the consequences of interpretation.” (Specifically discussing L’avventura, Brunette remarks that “. . . on a less exalted level, this sense of mystery is linked to the Barthesisan idea of the hermeneutic code of interpretation, by means of which we are led by every narrative, stupidly perhaps but crucially, to the solving of a riddle or puzzle. Our will to interpret, to make sense of things, parallels the characters’ search for Anna. . . .”)