II. THINGS

“A sudden light transfigures a trivial thing, a weather-vane, a wind-mill, a winnowing flail, the dust in the barn door; a moment,—and the thing has vanished, because it was pure effect; but it leaves a relish behind it, a longing that the accident may happen again.”

Walter Pater

Although some themes are common to all of Antonioni’s work, L'eclisse concerns certain, specific thematic issues to a greater degree than that found in any other film of the canon. The film, in a most basic sense, is a meditation on reification, obsessed with objects and things. (This obsession extends also to non-human living things, particularly trees.)3 In L'eclisse, the mutual resemblance and interaction between people and things, between the living and the dead, is so striking that the entire film--particularly its opening sequence--resembles that of a still-life (in Italian, “natura morta,” or, if you will, still-death).

The first shot of the entire film is that of Riccardo’s elbow placed alongside books and pieces of furniture. We do not know that it is an elbow until the camera pans and reveals its true nature as flesh. This single shot will be repeated in different guises throughout the film, and captures--in addition to the motif of recurrence and repetition--other issues such as reification as well as the deceptive appearance of the world. Towards the end of L'eclisse, there is a similar shot of Piero lying supine in a grassy field ostensibly in the Eur near what has been referred to by some critics (among them, Philip Strick) as an Olympic indoor cycling rink, only Piero’s bottom half visible in the frame. A panning shot then reveals his entire body, the strong, vertical spire of the supposed “rink,” its “steeple” in the background rising in a phallic manner from Piero’s solar plexus.*

The architecture of desire

In the 1964 screenplay published by Einaudi the building is identified as “una chiesa in stile nordico” (“a nordic appearing church”).4 In the original 1962 script contained in Lane’s book, L'eclisse, the building is referred to as a “velodromo” cycling rink for the 1960 Rome Olympic games. Such a velodromo does exist, opposite to the water barrel and construction site of L'eclisse at the intersection of the Viale del Ciclismo and Viale della Tecnica. This latter cycling rink is, however, an outdoor stadium which still exists (as of this writing), but has not been used for public events since 1968. (Additionally, in the early 1960’s the area around this large outdoor stadium was much more rural than it is today.) I cannot identify this strange building, or possibly, buildings (see Appendix 2 for an updated commentary as of September, 2008 regarding this building[s]). Did Antonioni in fact slyly make a single shot of two separate buildings superimposed upon one another to give them the deceptive appearance of one structure on the flat, two-dimensional movie screen? Or did Antonioni employ a kind of “glass or matte shot”--with either a photograph or painting in the background? Antonioni did compose such a shot in the opening scene of L'eclisse when we see the Eur water tower as seen from Riccardo’s apartment window as Vittoria opens the curtain. Such a perspective did not exist in reality, and Antonioni simply placed a photo of the desired object in the background against the window, a kind of simple “matte” or “composite” shot*. It would also have been possible, but more unnecessarily complicated, for Antonioni to have composed a true process shot in which in post-production he employed re-photography and an optical printer to combine two or more separate images into one. To my knowledge, the building with its strange spire appearing to arise from Piero’s groin--like so many other things in L'eclisse--no longer exists, or never existed in the Eur. Indeed, the outdoor velodromo referred to above--which does exist--will soon no longer exist; in 2006, municipal plans of Rome call for its transformation into the Città dell’Acqua (“City of Water”), which will house the largest facility for aquatic sports in all of Italy. Another possibility is that the strange appearing building exists, but that it is not in the Eur, or in Lazio, or even in Italy, but elsewhere. The first line uttered by Piero in this shot containing the foreign building is: “Mi sembra d’essere al estero.” (“I feel like I’m abroad.”). In the first shot of this scene, as we see Piero initially lying on the ground, we cannot see Vittoria. It is in a subsequent shot in the scene that we soon discover that Vittoria is lying immediately to Piero’s left. Is it possible that Antonioni has made a deadpan, existential joke, that Piero feels as if he is abroad--outside of Rome and the Eur--because he is truly “abroad”?* Is the shot of Piero lying on his back in what appears to be the Eur a composite shot of some kind, the unidentified building(s) in the background literally from “abroad”? Or if the building is indeed a painting of a building that does not exist, is Piero . . . nowhere?*

The opening sequence of the film takes place inside the suffocating and claustrophobic apartment . . . world . . . of Riccardo, a space where it is almost impossible to get one’s bearings. There is no establishing shot, no overview by which we might better understand where we are. Coupled with Antonioni’s other frequent violations of cinematic niceties such as his violation of the 180 degree rule, we become rapidly disoriented, or--in Antonioni’s hands--we become deliberately “disestablished.”* As Ted Perry has written, “The uncertainty of the present world is also revealed in a number of images which are initially incomprehensible and in other images where distortions of scale and perspective render the world partially unrecognizable and indeterminate.”

From the first appearance of Vittoria at the very beginning of L'eclisse--in this world of shifting appearances--we see her taking notice of a small, empty picture frame standing upright on a table upon which are sundry objects. It is this very frame that presages the final frame of the entire film, the “champ vide” referred to in French film criticism as “the empty picture,” or in the case of L'eclisse, an intersection in the Eur which Antonioni has depopulated in a forced evacuation. Vittoria places her hand through the frame, removes an ashtray from the other side, and arranges several remaining pieces of bric-à-brac. We see her hand literally interject itself into the picture frame as she composes her work of art. (It was not until 1967 that the “Arte Povera” [“Poor Art”] movement began in Italy, championing the use of discarded objects such as might be found in trash bins or rubbish heaps, cheap materials that might permit a “poor” artist to create works of potentially “rich” art.) If it is the empty frame and the objects on the desk that are the material for Vittoria’s art, then it is in turn Vittoria who is Antonioni’s paintbrush. It is Antonioni’s hand that guides Vittoria’s hand; Vittoria’s composition in the empty frame on Riccardo’s table is part of Antonioni’s larger composition called L’eclisse.

“The arranging consciousness”

Antonioni, in turn, then films Vittoria from the other side of the frame, as if from inside-out. This brief introduction to the main character of the film illustrates in a highly condensed form several of the principal themes of the entire film. From the outset, objects and things achieve center stage prominence. Vittoria is obsessed with objects and things. We observe her hand crossing the frontier between the real world and that of art as it enters the frame, transforming itself into a Thing of Art. She becomes both actor and audience, figure and ground, a dizzying composition of mirror and reflection. One is reminded of the artist’s hand painted in the self-portrait of Vermeer, “The Art of Painting,” as the hand itself enters the canvas within the canvas, upon which is painted leaves. At one time, Vermeer’s actual hand was, of course, poised above his canvas, as was the hand of Antonioni as it guided the camera outside the frame of his film (think of Borges’s “Ajedrez” in El Hacedor). The composition of this first meeting of Vittoria would be complete if only we could discern, however vaguely, Antonioni’s hand in the mirror of Riccardo’s apartment, as we view the foot of Vermeer’s easel in the mirror of his painting, “The Music Lesson.” (A Roman Charity--the painting of an old man suckling at the breast of a young woman--appears in both Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” and in Antonioni’s L’avventura!) Vittoria’s rearrangement of objects within the picture frame also adumbrates her later rearrangement of objects within the water barrel. That the barrel can be an easel and canvas also highlights Antonioni’s preoccupation with the interchangeability and mutability of objects and people in complex combinations and interactions (e.g., Objects become other objects, people transform into other people, objects and people themselves become confounded one with another). The barrel is also a frame. According to Magritte, ce n’est pas un baril. C’est aussi un cadre, une toile.* As already mentioned, the empty frame on the table of Riccardo’s apartment--an empty frame that does not hold the photograph of a happy couple, Vittoria and Riccardo hand in hand--also anticipates the empty cinematic frame at the end of L'eclisse, one also devoid, this time, of Vittoria and Piero in a pleasing portrait. Foreshadowing, duplication, mirroring, metamorphosis, and repetition are important motifs in all of L'eclisse. As we shall see, nothing happens, twice.

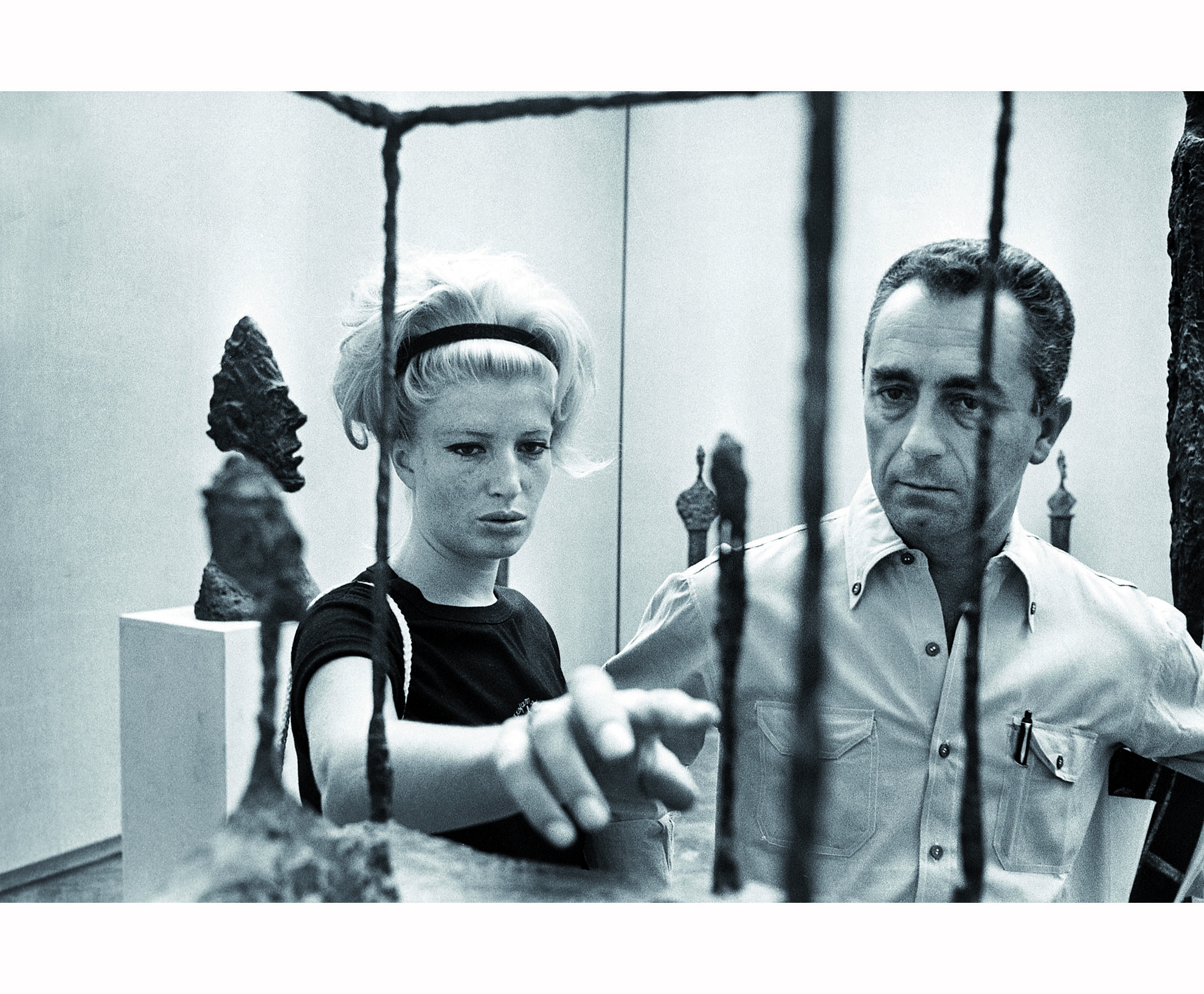

Monica Vitti and Michelangelo Antonioni at La Biennale di Venezia, 1962, in front of an Alberto Giacometti work of art

Not a celluloid Vittoria and Piero, but a real Monica Vitti and real Michelangelo Antonioni--two human beings who are none so blind but see--

attempting to see and manipulate a real objet d’art in an entirely deceptive world of appearances.

The picture frame within the frame of the movie screen also invokes the motif of the play within the play. Later in the film two brief scenes that are seemingly insignificant occur between Piero and a secretary of his office, Maria. In the first scene Piero asks Maria if she is angry because she must stay late at the office on this the day of the market crash. In the second scene that follows shortly thereafter in the evening of the same day, Piero exclaims that he now knows why Maria is angry, that she must be having problems with her boyfriend. Piero cynically remarks that Maria needn’t worry, that she will see her boyfriend tomorrow evening, that there will always be another sunset (“Lo vedrai domani sera. I tramonti non scappano.”). Piero’s philosophical musings take place with him seated with his back turned towards an open window that frames darkness punctuated only by the distant, white spot of a streetlight, blackness taking shape around a white point.* Piero turns his head to briefly gaze out this window which frames the void, not yet remembering that his own girlfriend, “la Bestiola” (“little beast”; diminutive of “la bestia” [“beast”]; potentially pejorative or affectionate as per context), is waiting for him on the sidewalk below. This fleeting, apparently inconsequential interchange is a film within a film. Maria and her boyfriend mirror Vittoria and Piero. The very conclusion of L'eclisse--its “sunset”--is foretold by Piero’s offhand philosophizing. The streetlight behind Piero’s back is a faint beacon foreshadowing the final light at the end of L'eclisse, a vanishing point towards which the entire film is lurching, a light which will be extinguished, a solar dead end or black hole. The reference to tomorrow evening is a direct and ironic allusion to the final interchange between Vittoria and Piero in which they promise to see each other “tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow . . . .” Piero is, of course, both right and wrong. Sunsets repeat themselves, and Maria may, or may not, see her boyfriend at the conclusion of the day. Vittoria and Piero will not, however, meet at their fateful intersection when day is done. (Likewise, in The Passenger, none of David Robertson’s-David Locke’s-Jack Nicholson’s appointments will be kept except for the final one, a rendezvous with death, an appointment--like that of paying taxes--that is generally considered inescapable.) Piero does not appreciate that the orbits of lovers and their conjunction are not as faithful as the flight of the Sun. Or as the Sicilian proverb more accurately predicts than Piero’s forecast:

Lu suli si ni va, dumani torna. Si mi ni vaju iù, non torno chiù!

(Il sole se ne va, e domani tornerà. Ma, se me ne vado io, non tornerò più!)

(The Sun leaves us and tomorrow it will return. But, when I depart, I shall be gone forever.)*

This brief scene involving Piero and Maria is typical of Antonioni’s putting big messages into small packages. The scene also reinforces the point already discussed, that nothing in a film by Antonioni, no matter how small, is insignificant. Finally, the scene with Piero and Maria--like the scene with Vittoria and the empty picture frame--is typically multilayered involving such Antonionian motifs as mirroring, foreshadowing, repetition, amorous conflict, and the creation of false expectation.

From the opening scene of L'eclisse we are confronted with a world saturated with objects, to which the camera’s eye is attracted to almost as great an extent as it is to people. In turn, Vittoria’s attention is drawn to the inanimate world, continually touching the objects she meets, as if her hands were an insect’s antennae bumping up against and communing with its physical environment. (As is their custom, Mancini and Perrella, p. 217, list in exhaustive detail all of the objects “caressed” by Vittoria in L'eclisse, a habit of other characters in other films by Antonioni as well. During the minute of silence for the dead broker--immediately after Vittoria has been introduced to Piero--Vittoria’s hand lies in state on the stone column separating her from Piero in the Borsa [“stock market”].)

Vittoria's touch

Perhaps the central cathexis that Vittoria experiences in the entire film is not with Piero, but with a small piece of wood, a cynosure, that she breaks off of a hoarding in her first visit to a construction site of a half-finished building at an undistinguished intersection in the Eur, a site that is the epicenter or ground zero of L'eclisse.6 Vittoria is intensely aware of this small, unremarkable piece of wood that she tosses into a water barrel, as opposed to the complete indifference of Piero to the cigarette matches that he subsequently and absentmindedly also tosses into the barrel. (Vittoria expressly searches for the piece of wood on her second visit to the intersection.) The matches land in the water in such a manner that they are lodged beneath the piece of wood.*

A broken piece of wood

These matches--as are the knickknacks that Vittoria plays with when creating a work of art on the table of Riccardo’s apartment in the opening scene of L’eclisse--are objets trouvés, a concept championed by Marcel Duchamp regarding the use of the banal, ordinary, “found” object as the stuff of art. One may be certain that Vittoria and Piero will someday cleave one from the other when Vittoria pointedly places her hand in the barrel and by touching the wood, but not the matches, separates the two.7

The broken piece of wood and the matchbook are divorced

One can only speculate as to the further play of wood and fire, or of the relationship between Vittoria, trees, and wood. It is also telling that Vittoria breaks off the piece of wood from a fence--as opposed to simply picking it up from off the ground--the wooden fence being one of the many barriers, bars, or obstacles that appear throughout the film. (At Vittoria’s second visit to the Eur water barrel immediately prior to Piero’s arrival at the site, she picks off a small piece of apparent bark from the trunk of a tree adjacent to the barrel, rolling the tiny piece of wood in the fingers of one hand; we do not see what she subsequently does with this second small piece of wood.)

In La notte during Lidia’s flânerie early in the film, Lidia wanders aimlessly into the confines of a fenced-off, abandoned building. A bell tolls off-camera in the background. Lidia encounters a small child (Yes, one more child in the film of a director who is sometimes said not to concern himself with children) who is crying, apparently the child of squatters on the abandoned property. Lidia then briefly contemplates a broken clock lying on the ground which—even though no longer functioning as a clock—chimes rhetorically as a kind of symbol with the bell we have just heard tolling. Lidia then breaks off a piece of the wall of the abandoned building, resembling perhaps wood, plaster, or a shard of rusted metal, an act analogous to what Vittoria will “later” do with the broken piece of wood in the next chapter, “L’eclisse,” of Antonioni’s single film. Although entropy will have its way and requires no assistance from us, both Lidia and Vittoria invest energy in hastening the deconstruction of matter. All of these objets trouvés—broken clocks, bits of wood, matchbooks—may, after all is said and done, incite only a barely audible murmur, “momento mori . . . remember you, too, shall die.”

Vittoria is repeatedly placed against the backdrop of trees, their leaves blowing, their branches swaying. (In the aforementioned scene from La notte, Lidia’s dress unsurprisingly bears a floral design.) We also view Vittoria intently viewing trees. The last scene with Vittoria entails the camera following her upward gaze, panning upwards towards a solid wall of trees.*

Before undressing and making love to Piero for the first time, Vittoria discovers in the apartment of Piero’s parents a novelty pen bearing the photograph of a an attractive woman. (Vittoria discovers this pen in what is the apparent childhood bedroom of Piero.) Depending on how the pen is tilted, the skimpy apparel (a one-piece black swimsuit or lingerie) of the miniature woman goes up or down, unmasking the woman in full frontal nudity.*

The shrunken object of desire

This, too, suggests the equivalence of Vittoria-human and Vittoria-object. We must remember the casual yet highly significant proclamation that Vittoria makes much earlier in the film, declaring the equivalence of beings and objects: “Che vuoi che ti dica? Ci sono giorni in cui avere in mano una stoffa, un ago, un libro, un uomo, è la stessa cosa.” (“What can I say? There are days when a piece of cloth, a needle, a book, a man are the same thing.”).8 It is not that Vittoria is the pen or piece of wood. Likewise, Antonioni’s frequent association of people with various objects does not appear to conform to such conventional terms of figurative language as simile, metaphor, symbol, personification, or to other rhetorical concepts such as the pathetic fallacy or objective correlative. (Seymour Chatman has argued that metonymy is the best descriptor of the kind of cinematic trope Antonioni commonly employs.) Ultimately, objects in Antonioni’s universe seem to stand for nothing else but themselves. They appear finally--remarkably--indifferent, flat, devoid of any meaning other than that which we care to varnish them with. A true ding an sich.*

Moses Gavriel, in writing of L'eclisse, repeatedly underlines the danger of trying to interpret Antonioni’s film by simply making an inventory of symbols and establishing their presumed meaning:

The interpretation of (such) symbols, however, should proceed with caution, for inherent in Antonioni’s orientation as a modernist is the inheritance of symbolist poetry which, Irving Howe reminds us, ‘wishes finally that the symbol cease being symbolic and become, instead, an act or object without reference, sufficient in its own right’. . . . Form becomes theme. . . .The continuity sought by Antonioni is thematic rather than narrative.

Perhaps, the entire conundrum as to whether Antonioni employs symbols or not is unnecessary. My own sense is that this is not an “either/or” argument. If you wish, have it both ways: look for symbolic meaning or reject symbols wherever you might find them. Consider that obscure objects that appear in L'eclisse are explained by metonymy or not. Does Antonioni particularly care? (Brunette quotes Antonioni as remarking that “Sometimes it happens that the films are interpreted differently from the way the director intended, but perhaps this isn’t important. Perhaps, it doesn’t matter whether films are understood and rationalized; it’s enough that they are lived as a direct personal experience.” [Brunette, p. 140].)

As Giorgio Tinazzi and others have remarked, it is not uncommon for Antonioni in L'eclisse, as well as in his other films, to allow the camera to linger on a lifeless object to the exclusion of human subjects. One thinks of the attention given to mechanical fans that becomes even more autonomous in the African hotel room of The Passenger. Things are protagonists. As Tinazzi has written, “Talvolta, la cura del particolare mira alla composizione asttratta, all’informale, col rischio di una ricerca preziosa, come avviene in certe inquadrature ‘inutili’, una sorta di natura morta.” (Loosely translated, “Occasionally, [Antonioni’s] attention to the particular leads to a kind of abstract composition presenting a vision of a dead and empty world.”) This focus on the life of lifeless things, leads to different narrative challenges than are encountered in more conventional storytelling . As Tinazzi again writes, “. . . le cose paiaono avere perso il rapporto di significato con il soggetto. Questa messa in crisi del rapporto soggetto-oggetto trova un analogo strutturale nella crisi del personaggio, non pìu visto come centro della narrazione. Nel finale dell’Eclisse sembra culminare una tendenza di tutto il film: il tessuto dell’esperienza ha smarrito il punto di riferimento (psicologicamente, direbbe il rapporto di consuetudine), e--in parallelo--la narrazione si slabbra, si sottrae ai nessi e ai rapporti.” (Again, liberally translated, “Objects seem to have lost their link with subject. This crisis of the subject-object relationship is also analogous to the crises experienced by (Antonioni’s) characters who are no longer viewed as the narrative center. At the conclusion of L'eclisse, the usual cinematic reference points are lost, disorientation ensues, narration breaks apart into bits and pieces no longer related one to the other.”) “Storytelling” decomposes, and approaches a documentary style of recording reality. However, even a documentary generally strives to offer an interpretation, or to tell a story. With Antonioni--particularly in the coda of L'eclisse--the camera begins to merely register or record. The historian stops interpreting the history of the world, and becomes a mere chronicler.

Contrary to most rhetorical convention, Antonioni’s subversive point may be that objects do not relate to people in any symbolic or other manner, but that people are only a special case in the taxonomy of objects, that people ultimately are objects.* Riccardo, slumped--molded--in his armchair, human arms resting rigidly on the arms of the chair, legs uncrossed, resembles a chair sitting on a chair (or as Ted Perry has written, Riccardo’s appearance resembles that of “a statue or corpse”). This posture is later reprised by Piero slumped in a chair in the apartment of Vittoria's mother, which not only reinforces the duality of objects-beings, but also the theme of the Double. At one point in the opening montage Antonioni’s camera views Vittoria from an unusual perspective of only inches above the floor. We see only her legs, waist down, next to the wooden legs of various pieces of furniture. (Vittoria’s legs are additionally “doubled” by their reflection seen on the polished floor of Riccardo’s apartment, a complex, exponential doubling--n to the 2nd power.) Later, in Marta’s apartment we see a table whose legs are those of an elephant (which Vittoria, as is her custom, touches). With hindsight, we may then ask whether in the opening scene Vittoria’s legs were also only pieces of furniture.

Elephant legs, table legs, Vittoria's legs

There are other pointed comparisons between living creatures and inanimate objects. Vittoria’s mother, for example, compares in a superstitious manner the figures of the stock market board in the Borsa to the “horns of snails” (“ . . .le corna delle lumache, si mouvono sempre.”).* Piero drives an Alfa spyder, an Italian sports car, that like many automobiles is named after an animal. It is also fitting that in Piero’s case his car also bears the less common appellation of a woman, Giulietta. Not only is there a linkage between animals and things, but there is also a frequent association between animals and people. (The argument goes that not only are Vittoria’s legs like those of a table, but they are also like those of an animal, a complex metaphorical twining.) One remembers the brief shot in the coda of L'eclisse of ants climbing a tree. Are we not invited to consider that other ant hill, the Borsa? As we shall see in Chapter IV, Marta considers black Kenyans to be monkeys.

What pen-wood-Vittoria have in common is that they are all things. Indeed, after Piero tears Vittoria’s dress in his parent’s apartment, Vittoria-Antonioni excuses the act by observing that inanimate objects are as animate as people, possessing a will of their own (“Se i vestiti si strappano, è colpa loro.” / “When clothes tear, it’s their fault.”). When discussing Kenya with Marta, Vittoria observes that in Africa, “Le cose devono andare avanti un po per conto loro” (“Things must have a momentum of their own.”). When Riccardo breaks the ashtray at the beginning of the film, whose fault is it?

Vittoria often stands alongside statues of humans--lifeless things. A striking example would be the relationship she enters into with the large statue in the form of a human being at the Palazzo dello Sport after searching for Marta’s dog. (Vittoria’s stature appears reduced as she stands next to the statue whose dimensions conform to a larger scale. As will be discussed repeatedly, Vittoria is “out of proportion” with the world and appears shrunken.) Busts of human heads adorn the apartment of Piero’s parents. Immediately after entering the apartment with Vittoria, there is a shot of Piero as he secures the front door of the apartment with a door chain, a black bust of a “Pan-like” figure next to him, Pan, a god famously associated with wanton sexuality. (Or--instead of Pan--does the small statue suggest the Pied Piper who lures children, in this case, Vittoria, to their death?) Antonioni incessantly assails us with overt juxtapositions, or better yet, superimpositions, of artistic figures--paintings and statues--and “real” human beings.* When Vittoria first enters the apartment of Piero’s parents she sits beneath a large painting of a young girl dressed in a white dress and white hat. Later in the same scene in the parent’s apartment, Vittoria sits on a divan beneath a large painting of an adult woman wearing a black dress with a black hat. (Represented in the painting aside the woman attired in black is a small mirror in which one may see the reflection of a tiny painting, a kind of complex mise en abîme reminiscent of Velázquez and “Las Meninas.”) The final shot of Riccardo that we witness in the opening scene of L'eclisse is that of a little, modern man--a leftist intellectual--his body literally slumped and crumpled against that of a large, abstract painting, a background that is nothing less than that of Modern Art.

Portrait of a little, modern man crumpled against the background of modern art

Standing next to him is a small statue of an unidentified figure wearing an apparent toga, perhaps an ancient man. As is the case with Vittoria at the Palazzo dello Sport, the statue is completely out of proportion to the size of the human being who stands next to it. As will be discussed later, the world of L'eclisse doesn’t conform to an architectural design in which the Creator adhered to just the metric system, a particular scale of, say, 1:64, a singular coefficient of correlation, or any other universal standard determined by some hypothetical, celestial system of weights and measures. It is not so much time, but space that is so out of joint, with no one in sight to ever set it right. When Vittoria appears for the second time at the Eur construction site, for a brief moment Antonioni films her as if she were the heroine of Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, towering above what looks like a modern city, a city that we soon realize is but a pile of neatly arranged metal construction tubing and material. As we shall later see, Vittoria resembles more The Incredible Shrinking Woman.

A particularly striking example of the juxtaposition of a statue with a human being--one that in the rhetoric of cinema suggests the equivalence of statue and being--occurs in the scene in the apartment of Piero’s parents. Piero has just “accidentally” torn Vittoria’s dress at her right shoulder. As Vittoria retreats from Piero, she walks in the direction of a Roman (?) statue of the head and upper torso of a woman that we the audience view in the foreground of the screen. As Vittoria flees in the direction of the statue we see her take notice of the stone figure, appearing to intently look in the direction of the figure’s head and its eyes. We then see Vittoria’s gaze descend to regard the torso of the statue, the right arm of which, like Vittoria’s dress, is truncated at the shoulder. As is typical of Vittoria, she touches the statue as she continues her flight from Piero. The physical juxtaposition of Vittoria and statue, a specific example in the rhetoric of cinema of montage regarding two objects in a given frame--montage occurring in space as opposed to time--suggests the equivalence of the stone woman with the woman of flesh. Montage in this sense functions rhetorically as a simile: Vittoria is like the statue. (Or in a more general sense, Vittoria and the statue are to be compared or contrasted with each other.) Such a comparison may invite a kind of guilty equivalence by association. Antonioni’s physical linkage between statue and being does not stop there, for he has directed Vitti/Vittoria to deliberately regard the statue, a shared gaze, an act of empathy that links the two, independent of rhetoric and montage. Vittoria and the statue understand one another, both of their arms having been torn at the same shoulder.* Antonioni does not resort to lap dissolves to suggest equivalence: a post-production, editing technique that I suspect Antonioni finds too “obvious.” Nevertheless, such dissolves are commonly employed by the greatest of film directors, such as Mizoguchi in The Life of Oharu (Saikaku ichidai onna, 1952) when a statue of the Buddha “dissolves” into an image of the character played by Toshiro Mifune, or in Buñuel’s L’Âge d’or (1930), when a photograph of a woman is metamorphosed into a real woman. Antonioni may eschew lap dissolves, but a tension exists in all of his films between an attraction to affectation, to the idiosyncratic, eccentric, novel, mannered, tricky, surprising, unexpected, and technologically inventive . . . versus an embrace of the pure and simple.

There is frequent framing of people in windows or doors frames, suggesting that people are themselves two dimensional bits of pigment organized on a canvas. (The actual images we see projected on the screen are, of course, also inanimate, offering only a refracted illusion of true movement and life.) In the opening sequence of L’eclisse, there is a shot of Vittoria on the left side of the movie screen plastered up against a closed door of Riccardo’s apartment, Huis Clos, facing us. Standing up against the well of the door, Vittoria is literally framed as she is transformed into but one more of the many paintings that adorn the walls of the apartment. On the extreme right side of the screen Riccardo is likewise framed by a door that is open as he exits the room, his back towards us.

The inverse may also occur when a painting seems to come alive. (Mitchell Schwarzer neatly summarizes the interplay between people and things in all of L'eclisse: “. . . humans are objectified and objects animated.” [“The Consuming Landscape: Architecture in the Films of Michelangelo Antonioni.” p. 210]). Two consecutive scenes open with a picture of a woman--in one case a painting of a woman framed by the real window of Vittoria’s apartment viewed from the exterior. In the scene immediately following, the first shot of Marta’s apartment is that of a large photograph of an African woman. In each case, we are asked to momentarily confuse an inanimate image with that of a real woman.* Each picture of a woman is then transformed into “the real thing” by the subsequent appearance/superimposition of a real woman. (Again, this cinematic effect is achieved not by employing the use of a dissolve, but is, instead, accomplished in a more organic and “lifelike” manner.) One might observe that the entire film is an elaborate trompe l’oeil.*

In L'eclisse, consider as an example of the deceptive nature of appearance, the piano bar that Vittoria and Piero stumble upon in the Eur. Antonioni pointedly films Vittoria and Piero from both in front and from behind as they stand together in back of an older couple seated at the outdoor bar.

Vittoria and Piero, redux

(The image of an aged couple and their juxtaposition with Vittoria and Piero is repeated several more times in the film: as Vittoria and Piero stand in the Borsa during the minute of silence for the dead broker, they are divided by a tall pillar and flanked on either side by Vittoria’s mother and Piero’s boss; Vittoria and Piero first make love in the bedroom of Piero’s parents beneath photographs hung on the wall of an older couple, presumably Piero's parents; in the coda, a fleeting glimpse of an older couple appearing on the roof of a Eur building is presented, stand-ins for the missing, younger couple.) Piero remarks that the pianist plays wells, and asks Vittoria who he is. Vittoria responds, “Dev’essere un vecchio.” (“He must be an ‘old-timer.’ ”). Vittoria and Piero then walk through the outdoor bar, and before exiting onto the street, we see in the distance in a medium shot a jukebox inconspicuously--oddly--placed against an outside building wall. As is typical of Vittoria, she pats the jukebox as she walks by.

Shoot the piano player

As Vittoria and Piero walk away from the bar onto the street we see two gaunt trees in the distant background atop a hill. Antonioni then places his camera on the apparent very spot where the two trees are, filming the two humans exiting the bar from the perspective of the trees, the dome of the Church of Santi Pietro e Paolo glimpsed inconspicuously in the distance.

This seemingly inconsequential and brief scene is loaded with import, allusion, and reflection. Both Vittoria and Piero--as well as we the audience--initially mistake a jukebox for a living pianist. This is a typical example of Antonioni deliberately inviting misperception (other examples will be given later). The scene also is a brief ode to reification, again insisting on the equivalence of people and objects and our inability to distinguish between them. Transformation is hinted at by our initially presumed living pianist later transformed into a machine. (One is also reminded of the mechanical origin of the music of African drums in Marta’s apartment, or the clanging of the flag poles heard by Vittoria after her search for Marta’s dog.)* Mirroring--an important motif in L'eclisse--is evident in the literal juxtaposition of Vittoria and Piero next to their older mirror image, the elderly couple. The jukebox, another mirror image, was anticipated by the jukebox of the airport bar of Verona. An even more compelling reflection is the final view of the two desolate trees on the hill in whose direction Vittoria and Piero are heading. Throughout L'eclisse, Antonioni repeatedly films robust trees whose thick foliage rustles in the wind. The two autumnal trees of summer Rome on the promontory outside the bar--a Golgotha like image--are an exception* (as is a completely leafless tree that forms a backdrop behind Vittoria and the metal tubing and building material of the Eur construction site).9 These two trees also hark back to the two headed rock of Lisca Bianca in L’avventura, juxtaposed with Claudia and Sandro. Like the dead and broken stick of wood in the water barrel of the Eur intersection, the haggard trees suggest a grim prognosis for Vittoria and Piero’s affair. The piano bar scene is also typical of Antonioni’s offhand manner of illustrating profound themes, multiple in nature, presented in a complex, layered amalgam. (Others have remarked that Antonioni has an abhorrence for the overtly dramatic or sentimental.) On a more tactical level, the scene also reminds us that Antonioni’s characters do not make idle remarks. Vittoria’s comment that “the pianist must be old,” is peculiar, and begs the question, “How does she know?” (The comment is reminiscent of other odd remarks by Vittoria—and by other characters in the film—such as when Vittoria states that she is “now shorter than she used to be,” or that she has “no nostalgia for marriage.”) As will be discussed further, Antonioni does not make irrational films in which his characters make nonsensical or idle remarks for no reason at all. Antonioni’s style of filmmaking may adhere to the dictum articulated by the movie director played by Humphrey Bogart in The Barefoot Contessa (1954): “A script has to make sense, and life doesn’t.” (To my mind any of the 3 other potential permutations of this dictum might, instead, be true: (1) A script doesn’t have to make sense, but life does. (2) Both a script and life have to make sense. (3) Neither a script nor life has to make sense.) In an Antonioni film, an initially obscure remark or image is a riddle waiting to be solved.* If things do not make sense--as in the entire world of Blow-Up--the unintelligible is presented in a rational framework. His films appear less open ended than a more abstract or surreal work of art. There is “method in his madness.”

A refined example of the equivalence of objects and living things is the fossil, a once living thing, now a lifeless piece of art hung on a wall. Likewise, we see the skull of some presumptive African game species--perhaps a feline head--now serving as bric-à-brac in Marta’s apartment. We are repeatedly shown a hybrid piece of furniture in Vittoria’s apartment that is part tree, part lamp, a kind of synthesis of the organic and inorganic. Given Antonioni’s evident interest in the relationship between people and things, between the living and the dead, such a piece of furniture represents a kind of synthesis or union resolving the tension that exists between two such poles. Representations, pictures and statues of living things, abound in L'eclisse. The smallest, perhaps most tender example of this is the small doodle of flowers (daisies . . . or are they, perhaps, “the last roses of summer?”) drawn by the curiously composed man who has been so particularly wounded by the crash of the market. (In the scene in the apartment of Vittoria’s mother—immediately following Vittoria’s examination of the doodle in the Piazza di Pietra—Vittoria is briefly shown in the sitting room of her mother’s apartment; the room is a veritable arboretum, enveloped by multiple paintings of flowers, the curtains and wallpapers bearing a floral theme.) The power of his simple scribble lies in its flowering in the midst of so much violence and ugliness in a piazza whose soil is that of stone.10 The doodle resonates with another representation in pigment of a fragile, living thing, the painting of a butterfly that Virginia purchases on a day when trees are being murdered in Il grido.* As is typical of Antonioni, although the literal weight of such images of flowers and butterflies is light, almost inconsequential, their meaning is substantial. Mute, small, insignificant objects such as pieces of wood floating in the dirty water of a construction barrel, deliver eloquent soliloquies on the state of things. (The “Butterfly Effect,” born out of chaos theory, suggests that the gentle fluttering of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil might produce a tornado in Texas.)

A diagram of the universe, adjacent to the hand of a man and of a woman

We might say that Vittoria has more of an affinity for representations of people--statues, photographs, and paintings--than for people themselves. A picture of a person is--after all--a thing. Not only does Vittoria appear to prefer paintings over people, but she seems to in turn prefer pictures of things more than pictures of people. During her visit to the apartment of Piero’s parents Vittoria does not ask any questions regarding the photographs or pictures of people that adorn the apartment’s walls. Vittoria does, however, expressly inquire about a landscape painting, a landscape with clouds. (Vittoria is so attracted to clouds during her flight to Verona--desiring to literally fly into them--that Anita, Vittoria’s neighbor, suggests that Vittoria is a cloud. All of which eerily anticipates the title that Antonioni would choose for his last film to be made some 35 years later: Beyond the Clouds.) Indeed, Vittoria’s relationship with things appears more abiding and constant that her relationship with the men in her life, Riccardo and Piero. (Are we ever told why her relationship with either of these men fails?)

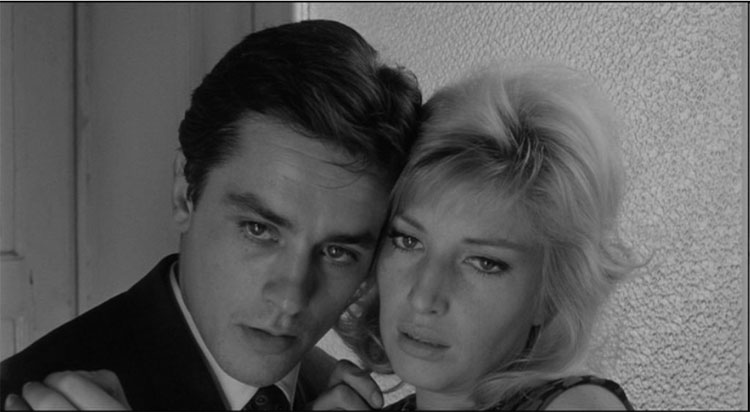

That people represent objects--or that art represents people as pigment, clay, or celluloid representations--is also suggested by Vittoria and Piero lying together on the couch in their final scene. Arms are akimbo, so knotted up that there almost appears to be one arm too many. The lovers awkwardly try to reposition themselves as if they were mannequins, the geometric solution to their anatomic problem eluding them, a pose resembling that of a Cubist painting.

“Tess, which are my hands and which are yours?”

They resemble puppets, an ironic reversal of the usual theatrical situation in which puppets are meant to suggest human beings. (Leprohon notes that a very early childhood interest of Antonioni was puppetry.)11 Given the incredible nexus of allusion in his film, it is remarkable that Antonioni--the ultimate puppeteer--did not more directly allude to literal puppets, dolls, or organ grinders in any scene of L'eclisse.12 One can easily imagine Vittoria and Piero outside the Borsa, pausing in front of a Roman--or better yet, Sicilian--street puppet show, laughing at the wooden beings. In Antonioni’s documentary on China, Chung Kuo Cina, Antonioni does film a puppet show at the Chang An Theater in Peking. The marionettes form a small orchestra that appear to be playing a march. On p. 36 of Antonioni’s script of the film he writes, “L’articolazione di queste marionette e la perfetta sincronia dei loro movimenti con la musica, dànno un’impressione di realtà sorprendente.” / “The movements of these puppets in perfect synchrony with that of the music gives a surprising sense of reality.” A toy robot does make a guest appearance in Il deserto rosso. Life-sized mannequins appear in Blow-Up, Zabriskie Point, and Identificazione di una donna, as well as “real” human models in Cronaca di un amore, Blow-Up, and Le amiche. (Renzo Renzi in his Album Antonioni includes in Antonioni’s filmography two documentaries that were apparently conceived, but never filmed: Modelle [“Models’]and Indossatrici [“Mannequins”].) Such figures--including the many statues that populate Antonioni’s films--are in a borderland state, dead objects resembling living creatures, a simulacrum of existence. They are the “apparitions d’être-objets” (phantom object-beings) of the surrealists (see Jon Stratton, Australian Humanities Review, retrieved 18 October 2006 < http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/AHR/archive/Issue-Sept-1996/stratton.html>). In L’avventura, Claudia mocks the robot-like behavior of the porter at the San Domenico Palace Hotel, performing a pantomime of his mechanical gestures. (In the early scene of L'avventura in Sandro's apartment on the Isola Tiberina [Tiber Island, the only island-ait on the river], Sandro mocks Anna--and in turn mocks Antonioni--by assuming a conscious pose, making fun of Antonioni's penchant for framing characters in door frames, balconies, and windows.) In their final scene together, Vittoria and Piero both mock the gestures of other couples whom they had previously seen, performing a tiny play within a play by miming their facial expressions, another metamorphosis, another mirror. Their ultimate metamorphosis is suggested by the poignant image of Vittoria and Piero, their faces side by side, frozen and facing straight ahead towards Antonioni’s camera, the transmogrification of two living beings into a lifeless frieze, the stuff of Art. A fossil hung on the silver screen’s wall, or as Keats might have imagined such an image on an ancient urn:

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

For ever warm and still to be enjoyed,

For ever panting, and for ever young . . .

Tomorrow, and all the days to come . . .

Indeed, at this the time when Vittoria and Piero are last together, they adhere to a description tragically, repeatedly uttered by the character played by Ingrid Bergman in Rossellini’s heart-rending Viaggio in Italia, in turn an utterance that might have been pronounced word-for-word by Michael Furey in Joyce’s “The Dead”:

No longer bodies, but pure ascetic images . . .

Not only do people resemble or equal objects, but time itself in L'eclisse becomes a thing. Time is, of course, money, as Piero reminds us after the minute of silence for the dead broker (“Qui un minuto costa miliardi.” / “Here a minute costs millions.”). Indeed, in a typical example of Antonioni repeating himself, Piero laments the death not only of the broker, but later in the film Piero also laments the death of the Drunkard, each of these deaths costing Piero both time and money. The cynical portrayal in L'eclisse of the minute of silent obsequy for the dead Italian broker could have been even worse. The Reuters news service reported that on November 17, 2008 “a trader shot himself in the chest on the trading floor of Latin America’s largest financial exchange [in São Paulo ]. . . . Witnesses said the incident happened in the interest rate futures pit, a raucous circle where on average $21 billion worth of contracts exchange hands every day.” Trading didn’t halt, not even for a minute; an ambulance came and unceremoniously carted the gravely wounded man off the trading floor, presumably to what we the faithless and hypocritical survivors still trapped in a fallen world commonly refer to as “a better place.”

Although the primary confusion in L'eclisse is between people and things, objects may also be confused with other objects. One example is the collection of neatly arranged metal tubing and building material at the Eur construction site that on closeup resembles either a cubist painting, or perhaps, the modern architecture of a city, the Eur (there is also a resemblance between the “metal building blocks” and the aereal view of Verona seen earlier in the film). Another example would be the momentarily confusing close up of branches and leaves studded with water droplets from a park sprinkler of the Eur, again resembling an abstract painting. (In a scene shot at the Museum of Natural History in Verona included in the 1962 Lane screenplay, but never included in the final film, Vittoria compares a fossil hung on a wall to that of an abstract painting.) Still others have remarked on the similarity between the Eur tower and the shape of an atomic mushroom cloud.* Flag poles become musical instruments (or as Gilberto Perez suggests, metal trees). Regarding the Borsa, Vittoria remarks, “Non l’ho ancora capito s’è uno ufficio, un mercato, o un ring. E, poi, forse non è meno necessaria.” (“I still don’t understand if the stock market is an office, a market, or a boxing ring. Perhaps it’s unimportant.”). While in the Borsa during the crash, Piero at one point screams, “Vita, vita, vita!” So depraved is this the world of Piero that life itself becomes a thing--a mere stock share--to be bought and sold. What precisely Piero means by “Vita, vita, vita! is ultimately unclear. In the extreme lower left corner of the grand board of life and death hovering above all in the Borsa, “VITA” is listed as presumably the acronym or name for some stock or commodity (“VITA” is visible on the board in the second scene in the stock exchange using the zoom function of the DVD; “VITA” is also easily visible with the naked eye in a photograph in i film di Michelangelo Antonioni, 1985, Biarese and Tassone, p. 114). The literal translation of “vita” would be “life.” While the market and the sky are falling, is “Vita!” a cry for help? “Vita” is also an Italian nickname for Vittoria, a shortening which renders Piero’s call for Vittoria in the hell of the Borsa, plaintive, a tragic play on words. This urgent cry, the repetition of three words in exclamation in a former temple, now desecrated, may, in fact, be among the most poignant moments in all of L'eclisse. “Vita, vita, vita!” an incantation, a supplication, a prayer . . . Piero, in a rare moment of humility, the subconscious crying out in pain, God, please make it so, forsake me not . . . or on a more chilling and less plaintive level, Piero’s cry of “Vita!” makes Vittoria and a stock one and the same (the very clarion call of objectification/reification we saw earlier in the first moments of the first scene at the Borsa when a trader suggests that a woman represented by a cheesecake photo has a market value). There is also the “clang association” with the surname of the actress who plays Vittoria, Monica Vitti. Lastly, the Criterion DVD English sub-title translates, “Vita, vita, vita!” as “Go, go, go!” (“Hurry up!), a possible mis-translation, related to a misleading similarity with the French adverb/adjective, “vite,” meaning “quickly; fast.” “Morte, morte, morte!” makes as much sense.

In L'eclisse Antonioni has the tendency to present incomplete images of objects and people. The film begins with a shot of Riccardo's elbow, a piece of the man. When Vittoria lies on her childhood bed in her mother’s apartment we see only her bottom half, a posture repeated with the “steeple shot” of Piero towards the conclusion of the film.

What is in the frame?

The appearance of the enigmatic, old man at the Eur street corner in the final montage begins with a fragment of his face, before preceding to the whole. Think of the initially cryptic cut to the edge of the airplane wing en route to Verona. Even with the auditory clue--the droning of the airplane’s engine--the appearance of the fragment of the plane does not initially reveal the whole. The bus careening past the intersection of the Eur in the coda is reduced to a shot of its wheel and hubcap. The aereal shots of Rome and Verona are limited in their scope, revealing only parts of the two cities. This in turn leads to a possible confusion—especially for a viewer unfamiliar with Italy—between the coliseum of Rome and the arena of Verona, an act of duplication as well as an invitation to become disoriented that is typical of Antonioni. As already noted--contrary to usual cinematic convention--the very opening of L'eclisse does not constitute the traditional establishing shot. Instead, we are shown only fragments of Riccardo’s apartment from different camera angles. (As already noted, we are initially shown only a fragment of Riccardo’s body, something which initially looks like a piece of furniture, but is instead, his elbow.) As is the case with the Photographer’s studio in Blow-Up, it is almost impossible to get one’s bearings. We never gain a comfortable sense of the layout of Riccardo’s apartment, its space, its geometry. This spatial disorientation is deliberate on Antonioni’s part insofar as he frequently violates the 180 degree rule, employs unusual camera angles, will suddenly flip the camera around and present us with a confusing new perspective of an object or person just viewed, places the camera in “impossible” spots (such as the shot of Vittoria taken with the camera placed behind Riccardo as he sits slumped in a chair placed tightly in a corner where no camera should be able to fit (“wild walls” as opposed to a “practical set”), confuses us with reflected shots employing mirrors, clutters the room with art and bric-à-brac everywhere, and so forth. As Angelo Restivo writes in a different context, it is as though Bazin’s myth of total cinema were exploded, presenting us with “an infinity of virtual points of view, none of which can be decisive in telling us the truth of the event. We are (instead) confronted with a totality that cannot be grasped.” (Restivo, The cinema of economic miracles, p. 106). As Chatman observes, the final minutes of L'eclisse constitute a “disestablishing” shot. One may even wonder whether L'eclisse would suffer less than most movies by being viewed in reverse.*

All great art avoids the declarative; a particular feature of Modernity is the deliberate refusal to be “easy.” In keeping with such a fondness for deliberate obfuscation, I defer to the reader to decide why this should be so. (While in the Musée d'Aquitaine of Bordeaux in July, 2022, I saw a large reproduction of a 17,000 year-old paleolithic cave painting from nearby Lascaux of the Vézère valley in southwestern France. Mounted on a wall next to the painting was a museum expository note highlighting that, “These cave paintings were not necessarily meant to be seen.” I thought to myself: In 17,000 years we have evolved from creating art that is not necessarily meant to be seen to creating modern art that is not necessarily meant to be understood.)

Dialogue is scanty in the film, again suggesting the primacy of a mute, inanimate world.* Objects may, however, occasionally speak, and when they do Vittoria attends to their language (she is, after all, a translator). The sound of drums emanating from a mechanical device--the phonograph of Marta’s apartment--mesmerizes Vittoria (the mechanical bird singing in the tree of Yeats’ Byzantium).* One remembers the hypnotic power that the clanging of the tall poles swaying in the wind holds for Vittoria (as if the poles and their wires were the staff and strings of the lyre of Orpheus, Vittoria spellbound. Indeed, the power of Orpheus and his lyre was such that trees, rocks, and wild beasts were said to be attracted to his music). This is not human speech--German or Spanish--but the language of objects. As will be noted later, Vittoria also speaks the language of dogs. (Vittoria’s future cinematic relative, Giuliana of Il deserto rosso, in the nightmare of tomorrow will lose this capacity to communicate in her encounter with the Turkish sailor. The curse of Babel will be even more completely realized in The Passenger where from the opening scene David Locke finds himself repeatedly in nations whose languages he does not speak.)13 Antonioni is commonly regarded as a director more interested in the image than the word. Indeed, his dialogue is frequently criticized as awkward or even nonsensical (which in some cases, as in Blow-Up, may be deliberate). L'eclisse is a kind of silent film, silent films being the kind of movie that Hitchcock referred to in his famous interview with Truffaut, as “pure cinema.”What is Antonioni suggesting by this elaborate linkage between the world of people and objects? I think it overly facile to simply conclude that in our time we are witnessing the industrialization of human beings, their loss of humanity, and resemblance to things, their becoming participants--action-shares--in the tarantella of the Borsa. (This theme is raised in Antonioni’s subsequent film, Il deserto rosso.) L'eclisse strikes me as less “sociological” or “psychological” as opposed to philosophical, existential, poetical.* (A “lyrical” view of L'eclisse conforms to the fact that Antonioni wrote the screenplay in collaboration with three highly regarded Italian poets, Tonino Guerra, Ottiero Ottieri, and Elio Bartolini. This highly unusual screen writing team may explain in part the perhaps unique literary quality to L'eclisse. Despite the fact that American literary luminaries such as Faulkner, Fitzgerald, and Steinbeck have moonlighted in Hollywood, I cannot think of a single American film ever conceived by a similar cadre of director and poets.) Although, for example, Vittoria and Piero first make love beneath photographs of Piero’s parents, is this an invitation on Antonioni’s part to engage in psychoanalytical speculation, or instead, to consider whether Piero’s parents have been transformed into things, family portraits, dead fossils hung on a wall? Chatman refers to L'eclisse as a “classic example of an open text,” in which any single interpretation might diminish the rich, multi-layered meaning of the film. As Chatman has noted, does the water escaping from the drum at the conclusion of L'eclisse merely symbolize the end of Vittoria and Piero’s relationship, or is there a more complex resonance, sand falling from the hourglass of eternity?