VII. THE END IS NEAR

“At the Formula One Italian Grand Prix in Monza, a horrific crash at the 2nd lap of the race causes the death of German driver Wolfgang Von Trips and 13 spectators hit by his Ferrari.” September 10, 1961

(retrieved 4 July 2006 from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/September_10>)

As I lay dying . . . the woman with the dog’s eyes would not close my eyes as I descended into Hades.

The OdysseyBook 11

In a conventional sense, we know very little about any of the characters of L'eclisse (e.g., Where are Piero’s parents? Are they dead or alive?). As is typical of Antonioni, what we learn about them comes not from overt declaration, but in more subtle and oblique ways, often suggested by action and not word. Instead of informing us that Vittoria, for example, is a member of some hypothetical green party of the 1960’s, we see her gazing at trees or tapping repetitively on a wooden table. Biographical data, one’s true curriculum vitae, is suggested or implied, as opposed to declared. When Vittoria is shown a photograph of Mount Kilimanjaro in Marta’s apartment she observes, “The snows of Kilimanjaro,” informing us that she has read Hemingway and is not a bimbo.30 In conventional narrative terms, characters are sketched or “blocked out” (a description that William Arrowsmith employs), and remain deliberately vague, two dimensional stick figures plastered in a mural against a white wall, the movie screen. As will be further discussed, many characters make brief appearances that are entirely unexplained and without any of the niceties of polite, cinematic introduction. The eerie music sets the tone of the Mysterious. As in Blow-Up, human beings are eventually effaced or eclipsed by objects. The Photographer disappears as does the Girl, the cadaver, and all of the photos taken in the park, save one, only the grass remaining.* As for man, his days are like grass; As a flower of the field, so he flourishes. When the wind has passed over it, it is no more, And its place acknowledges it no longer. Psalm 103:15-18. Indeed, if one examines in slow motion, frame-by-frame the scene occurring towards the conclusion of Blow-Up when Hemmings apparently believes he sees the Redgrave character standing at night on a London street amidst a crowd, she literally appears to suddenly vanish into thin air. Likewise, if one watches in slow motion the very last image of Anna in L’avventura, she “dissolves” into a void of cinematic nothingness while the remainder of the shot appears relatively intact. I suspect that the cinematographic “trick” that Antonioni employed concerned a process shot combining two separate images of Anna and Sandro respectively, followed by an asynchronous and accelerated dissolve of the image of Anna before the fade of Sandro’s image (“speed ramping” employing an optical printer in post-production). This sleight of hand is faster than the eye and occurs so quickly, so subtly, that at normal viewing speed the image(s) of Anna and Sandro seems to be dissolving simultaneously in a conventional transitional fade. The magic trick is, thus, to disguise a “double dissolve” as an apparent single one employing a clever, imaginative, but simple legerdemain. Antonioni does not stop there: after the image of Anna has disappeared, the remaining image of Sandro melts appearing to show his metamorphosis into lava and then hardening into rock. Alternatively, Antonioni may have employed “double printing” using an optical printer. Kawin describes the technique in How Movies Work (p. 428): “More than one original is copied onto the dupe and the images are superimposed. Relatively underexposed images will appear transparent (‘like phantoms’); fully exposed images will appear solid.” There is, however, a problem here: The asymetric dissolve of Anna is practically invisible under normal viewing conditions. Most filmmakers create such visual effects in order that they may be seen and appreciated (I suppose that some filmmakers might be satisfied with even a “subliminal” appreciation of the visual effect). Antonioni, however, appears to have produced a stunning visual effect that is hidden in plain sight and that—even if spotted—demands of the viewer the extra step of inquiring: “Why did Antonioni do this?” The answer, unlike the image, seems clear: Anna is disappearing. In Endnote #18 I cite in a different context the advice of Bresson and Ozu. Bresson recommended in “Notes Sur la Cinématographie”: “Hide the ideas, but so that people find them. The most important will be the most hidden.” Or as Ozu advised: “Hide what the spectator most wants to see.” But is there a paradox from which we may never escape in Magritte’s “observation” that “Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see?” Once the hidden is revealed, what secret is hidden by the revelation?

There is also a remarkable similarity between the endings of both L'eclisse and The Passenger. In the codas of both films, spoken language is largely expelled. The camera assumes a kind of consciousness or autonomy as it conducts its own inventory of banal events in an undistinguished, public place at day’s end. “All these moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.” The conclusion is that of disappearance or of death, or as Pechter has written, “ . . . another of those Antonioni ‘still lifes’, mysteriously reverberant with the sense of something momentous and ineffable which has taken place and left its residue.” (quoted by Chatman, p. 185).31

As already noted, at the end of their first meeting at the intersection of the water barrel, Vittoria departs first, walking down the middle of the street away from Piero, her back turned towards him. Piero then takes several steps out into the street of the intersection, stops, and gazes upon her departure. Seconds later, Vittoria takes one last glance behind her, but Piero has disappeared, foreshadowing the eventual disappearance of both Vittoria and Piero at the conclusion of the film, both figures replaced by concrete and asphalt (a fate shared by Lot’s wife who dared to look back at Sodom and was turned into a pillar of salt.)* One might regard L'eclisse as a paean to the God of Reification, a Medusa whose gaze turns men into stone, who has created a reified world in which dumb, mute objects announce no conclusions, state no themes, stand only as an end in themselves.

On a playful, seemingly innocuous level, the eventual annihilation of people from the face of the film is heralded by a game of hide-and-seek that both Vittoria and Piero independently play. In a fleeting scene, interpolated into the general tumult of the Borsa, Piero lightly taps from behind the shoulder of a broker. When the unidentified man turns around, Piero--who has already darted away--has disappeared. All that remains is a perplexed look on the face of the broker. Similarly, while standing near the empty and abandoned baby carriage in a largely deserted appearing street of the Eur, Vittoria suddenly whistles loudly at a postman on a bicycle whose back is turned to her. When the postman turns to see who has whistled at him, Vittoria herself has now turned away, giggling and feigning innocence. Piero, standing nearby simply shrugs his shoulders to the postman, playing dumb. (Earlier, Piero’s soul mate, the Drunkard, had similarly shrugged his shoulders in a gesture of existential incertitude.) Note also that Antonioni has given us not one, but two seemingly trivial scenes of hide-and-seek. Such a child’s jape may be seen as a practice session or rehearsal for Vittoria and Piero’s final disappearance.

As will be discussed further, repetition-duplication-mirroring represent an additional independent and important motif of L'eclisse. One scene may reinforce or help to decipher the hitherto obtuse significance of an earlier scene. Furthermore, a complex layering of themes and motifs may occur in a single scene. In the example given above of Vittoria whistling, there is a confluence of hide-and-seek, effacement, the “empty vessel” (e.g., baby carriages without babies, chocolate boxes without chocolates, frames without pictures, matchbooks without matches, love stories without any love), repetition, and the sudden appearance of a new character (the postman) who will suddenly pop up out of nowhere, assume a momentary importance, and then disappear forever.

Think of the handsome, young, blond man who briefly appears crossing the Eur intersection at the time of Vittoria and Piero’s final meeting at the barrel. Vittoria who is walking with Piero, suddenly stops, unabashedly turns and stares at the back of the unidentified, blond man as he walks off screen into oblivion. She openly remarks, to Piero, to herself, as if to no one, “Hai visto che bella faccia?” / “Did you see what a beautiful face?” The entire film stops for this stranger, as if L'eclisse were a car waiting for a pedestrian to finish crossing the street. Who is this man? No one. Bello da morire.* (The young, blond man is--if you wish--an older version of the anonymous, fair-haired boy who in an unmotivated manner intersects the path of Vittoria and Riccardo towards the beginning of L’eclisse. As such, the two scenes--little, blond boy and young, blond man--conform to a typical Antonionian mirror scene. We don’t know who these characters are, a ubiquitous theme in Antonioni’s films. How much more do we know about any of the characters in L’eclisse? Does anybody really know who anybody else is, let alone the man in the mirror?)

Look in the mirror. Does anybody know who anybody is?

At night, trying once more to see Vittoria, Riccardo furiously shakes the locked front door of her apartment building. Piero must turn a lock 5 times before gaining admittance to his parent’s apartment where he will seduce Vittoria. The traders in the Borsa are surrounded by a gate, as if oxen in a pen. One of the few gates left unlocked in L'eclisse is opened by dogs seeking to escape. Some critics have interpreted the ubiquitous bars, curtains, pillars, and the like--barriers that appear to separate people in the film--as a metaphor for the impossibility of love in modern times.* An alternative view would be to regard such obstacles as a kind of blind in which one is concealed in a game of hide-and-seek. Likewise, much has been made by some as to the significance of the evanescent woman who appears briefly framed by a window across from the apartment of Piero’s parents. (Vittoria later mirrors the appearance of this woman when Antonioni allows us to view Vittoria from a perspective outside the apartment as she opens the shutters to peer at the piazza below.)32 This, too, may be seen as a kind of directorial sleight of hand or prestidigitation on Antonioni’s part. One might observe that not only do the people (and dogs and things) of L'eclisse engage in hide-and-seek with each other, but that Antonioni does so with his audience. As with the Photographer of Blow-Up, we watch Antonioni’s creatures watching others. And when such creatures eventually disappear--whether in the coda of either Blow-Up or L'eclisse, or in the prologue of L’avventura on Lisca Bianca--we remain the only witnesses to the void. Soon, after the final streetlight of L'eclisse and the film itself have been extinguished, we, too, will arise from our own theater seats, the cinema again empty, silent, illuminated.

A director such as Antonioni who enjoys a highly intellectualized form of cinematic hide-and-seek, will not generally moralize, be pedantic, nor make overt declarations of intent. The near absence of “commentative” music in his later films attests to Antonioni’s reluctance to utilize crude means to manipulate our emotions. Chatman quotes a similar reluctance on Antonioni’s part to use the device of voice over-interior monologue, quoting Antonioni as having said, “It’s too easy.” Given then, Antonioni’s preference for allusion or oblique declaration, it may seem highly atypical that he should show us in bold relief magazine headlines referring to “LA GARA ATOMICA” (“THE ATOMIC RACE’) and “LA PACE È DEBOLE” (“ THE PEACE IS WEAK”), held in the hands of an unidentified pedestrian exiting a bus at the now infamous intersection of the final montage. Indeed, some critics have seized upon this intrusive, thematic declaration and used it as a handle for understanding the vagaries of the entire film. In this light, L'eclisse becomes a tale of existential angst in the atomic age.33 My own view is that there is less, or perhaps more here than meets the eye. The newspaper appears in the coda of the film, from which the main characters have departed, and from which the spoken word has been cast out. (In Zabriskie Point the characters “Mark” and “Daria” paint on the side of the stolen plane, “No Words,” a declaration made of words.) Objects have assumed a remarkable primacy, so much so that in the final coup of the film--reminiscent of a cheap science fiction movie--the alien robots have expelled the humans and taken over the world. The human voice is extinguished, and it is now only things, black and white figures on a barren field that speak. The sound track--music, again reminiscent of a science fiction or horror tale--also comes blaringly to life, for it, too, is a thing in a world now without musicians.

Violent death lurks everywhere, the mushroom cloud of the atomic age looming before us. Ironically, Vittoria and Piero had less to fear from an atomic bomb than they did from their creator’s hand, for it is Antonioni and he alone who will efface their existence at the conclusion of his film, two names scratched out from the script of celluloid life on a day of atonement, or of judgment.* Antonioni gave, and Antonioni hath taken away. The wake of L'eclisse is awash in the detritus, flotsam and jetsam of death. Look carefully enough, and as in Holbein the Younger’s painting of Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve (“The Ambassadors”), a skull will be evident in the foreground of the film. In the coda, follow along with the camera’s eye the trail of water from the mysteriously punctured barrel as it flows down the sidewalk to the gutter before returning to the sea. Perched at the sidewalk’s edge, hanging perilously above the gutter is a drenched piece of paper which undoubtedly if saved, unfolded, and left to dry would reveal a small doodle of daisies. Beginning at dawn and ending at dusk, L'eclisse is a long day’s journey into night. In the opening scene, the journal, Il Contemporaneo, with an apparent picture of a firing squad resembling Goya’s “Los fusilamientos del 3 de mayo” lies casually on a table in Riccardo’s apartment. (Jacopo Benci identifies the cover illustration as “Fucilazione in campagna.” See Benci’s “Michelangelo’s Rome: Towards an Iconology of L'Eclisse,” Note 14, p. 81.) Later, in The Passenger, the firing squad will no longer be limited to the sanitized vision of death drawn on a journal cover. In Marta’s apartment Vittoria will herself face a firing squad as the hunting rifles hung on the wall appear to point directly at her on the flat, 2-dimensional screen of the cinema. Chekhov’s gun.* In Piero’s boyhood room just prior to his seduction of Vittoria, a picture of a toreador slaying a bull hangs on the wall (not the snows of Kilimanjaro, but death in the afternoon.)* Marta may be quite afraid that blacks in Kenya have revolvers, but she herself shoots a child’s balloon in the middle of Rome with a high powered hunting rifle (an act with terrible mnemonic power, reminding us of the death of hippopotami and elephants). Marta’s entire discourse is laden with apprehension regarding Kenya, her summary statement being: “Ho paura, però, che sta per scoppiare qualche cosa.” / “I fear that something is about to explode.” This is a prescient remark, for soon Marta will blow up the balloon, as if it were the world itself exploding. (Prescient, indeed, for--as of this appended parenthesis written in early February of 2008--Kenya, one of the more relatively prosperous, developed countries in Africa, has descended, as has much of the rest of Africa, into a downward, spiraling hell of internecine conflict and human cruelty . . . as has, as of this very moment, the African nation in which both David Robertson and David Locke died: Chad. And what of the financial meltdown of the entire world in 2008? It was not so much that Antonioni knew it was coming, but that he, like Ecclesiastes, had seen all of it before: the panic of the market, the traders and brokers like frightened animals, clinging to the edge of the abyss in the Borsa by their claws, the maw of hell looming below. No, not yet the last judgement, but only a recurrent one.) Antonioni has never been characterized as a director with a strong political dimension (in the sense, say, of Gillo Pontecorvo). And yet, Antonioni has expressed an intense, abiding, and explicit interest in politics, an interest that occasionally surfaces in his films, particularly The Passenger. Brunette (p. 139) refers to an interview that Antonioni had with Alberto Ongaro in which Antonioni said, “I do take an active interest in politics, I follow it closely. Naturally, I am interested in politics in my own way, not as a professional politician, but as a filmmaker. . . .” Indeed, Antonioni is commonly regarded as a “Marxist” as well as an “atheist,” but I wonder if the truth is more tangled and elusive. In the early 1980’s, Antonioni worked closely with the Catholic church on one more aborted film project never to see the light of day: a film of the life of St. Francis of Assisi (to be played by Roberto Benigni!). Antonioni apparently invested a tremendous amount of time in the project which resulted in a 148-page screenplay that appears destined only to an eventual conversion someday into dust.

(http://www.fraticappuccini.it/attualita/rassegna/print.php?id=11616 [retrieved 8 February 2008]).The priest with whom Antonioni worked on the project felt that Antonioni was not an atheist, but a man of great faith. I do not know if I believe in biographies, or histories, or film criticism, or whether such books ever capture the “truth,” especially regarding a man as private as Antonioni and the art he drew. A similar difficulty exists with another Catholic director of Antonioni’s generation with whom Antonioni is sometimes compared, Robert Bresson; Bresson once described himself as a “Christian atheist,” a seeming oxymoron that might apply to Antonioni as well. (Carlos Fuentes once wrote of Buñuel and Ingmar Bergman that they were “part of one of the most compelling, if uncategorizable, intellectual tendencies of the 20th century: that of religious temperament without religious faith.” [En Esto Creo / In This I Believe]). I am not surprised to find that anyone regards Antonioni as politically conscious, pious, or anything else. This should not be surprising considering that Antonioni presents himself as a man who is interested in everything. All of Antonioni’s films have “come true,” in the worst possible sense. All of Antonioni’s films remain relevant and are being replayed in the vicious cycle of history--the nightmare of James Joyce of a history of Ireland, of the world, a nightmare from which Joyce, Antonioni, could not awaken. My own bias is that all politics is, indeed, deeply “local,” the primordial determinant of each and every political act being ultimately based in the parliament of the mind, the checks and balances divided between the not-so-equal co-branches of the government: the Ego, the Superego, and the Id. (Or, if you prefer, Shelley, the final line in his “Defense of Poetry”: Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.) This evening, somewhere, someplace, the same tragedy will be replayed: at 20.00 local time two lovers will not keep their appointed rendezvous. Their vote, as recorded in the Congressional Record, will be: “not present.”

Vittoria may relish the role of innocently playing black, but she brandishes a spear in her hand. In Vittoria’s final encounter with Piero in his office she transforms

L'eclisse: Heart of Darkness

herself into a lioness, playfully growling and clawing at Piero as they wrestle on the floor. (Earlier, we had seen how dogs may transform themselves into men.) One again thinks of Freud, jokes, and the unconscious; behind the joke may be the real “latent” message: “Be careful. Sex is dangerous. I might kill you.” (The very title of Kiss Me Deadly [1955]--a remarkable hybrid of film noir and atomic bomb cinema--suggests this linkage between Eros and Thanatos.) The Drunkard may fulfill the cinematic stereotype of the comic drunk, but he ends up very dead, his hand pathetically dangling out the driver’s window, waving goodbye. At Vittoria’s second visit to the half-finished building at the Eur intersection she stands next to a neatly arranged pile of metal tubing and construction material that at first resembles a city. In the final minutes of L’eclisse we again see the metal tubing and material, this time in total disarray, or as Cowie writes, “. . . crumpled in confusion like a city wrecked by nuclear attack.” Stock markets, like stars, collapse inward upon themselves. Although these and other images suggest overt or latent violence, L'eclisse ends not with a bang, but with the vision of an annihilated world peopled only by objects and things (or as Chatman has remarked, a post-neutron bomb world emptied of people--buildings and things left standing). Objects are even further devalued, emptied of meaning, by removing their contents. One thinks of the baby carriage without the baby. The box of chocolates without the chocolates. An empty matchbook. The empty frame in Riccardo’s apartment that Vittoria manipulates. Parent’s homes which do not contain parents. Marta’s apartment may be filled with photos of Africans, but there is no husband nor child. A dirty wall in Vittoria’s childhood room outlines the spot where a picture once hung, now vanished. In the Eur, streets are curiously silent, devoid of cars.* The frenzy of the piazza that fronts the Borsa only heightens our awareness of the barrenness of the final intersection outside a half-constructed building, itself empty, a construction site devoid of any laborers. Antonioni wrote in his 1964 screenplay (Einaudi) a description of the piazza that Vittoria gazes upon as she stands by a window in the apartment of Piero’s parents: “Tutto un mondo fermo e stanco, come in attesa di morire” (“A tired and paralyzed world, as if waiting to die”). As Vittoria and Piero lie playfully on the floor of Piero’s office in their final scene together, a wall clock is visible in the background behind curtains gently blown by a summer breeze. This comic playfulness is utterly remarkable when one considers that literally within several minutes of this delightful moment Vittoria and Piero will—at least within the confines of the film, L'eclisse—never see one another ever again. As is the case with some clocks, surely this timepiece bears the Latin inscription in tiny letters beneath the hour hands or on its reverse side: Vulnerant omnia, ultima necat (“All the hours wound you, the last one kills.”) In the case of L'eclisse the final hour of the clock will be 20.00. This Roman—as opposed to University of Chicago—doomsday clock, showing the time to be 14.32, indicates that it will be only 5 hours and 28 minutes till Zero Hour, the end of Vittoria and Piero . . . and the world. Not Germania but, Italia, anno zero.

But thought's the slave of life, and life time's fool;

And time, that takes survey of all the world,

Must have a stop.

Henry IV, Part 1. (Act V, Scene IV)

Papers, perhaps calendars, flutter on the walls, waiting to be blown away, joining those other papers already tossed into the Tyrrhenian Sea in L’avventura or into the Po in Il grido, lost forever. A buzzer rings, apparently the front door, and not a telephone. Who is there? Both Vittoria and Piero are caught off guard--Piero’s mouth literally agape, his gaze wide-eyed--as they both stop their romantic frolicking and look in the direction of the sound of the buzzer. And when Piero opens the door, no one. (Such a buzzer also sounded in the Borsa at the beginning of Vittoria and Piero’s relationship signaling an announcement of death.) After Vittoria and Piero suffer their final separation, Piero sits alone at his office desk, the atonal, arrhythmic music of unanswered telephones ringing, another minute of silence recalling that earlier minute of silence in the Borsa--unanswered telephones ringing--the requiem for a dead broker.* Vittoria takes leave of Piero, walking down flights of stairs because apparently the elevator is not working (reminiscent of the final act of Locke’s flight from himself in The Passenger when his car breaks down). In the final minutes of L'eclisse, a segment sometimes referred to as a “coda” (although the terms epitaph or obit might serve equally as well), we see the water barrel for the final time. The barrel is at a “de-construction site,” a place whose foundation--to steal a line from Identificazione di una donna--is “costruito sul vuoto” (“built upon the void . . .”).34 Vittoria and Piero no longer keep the barrel company, and the water butt--when viewed from above--is slashed diagonally by a peculiar white line (a kind of metal wire handle to the barrel?) as if it were transformed into a traffic sign forbidding its own existence.35 The barrel is now mysteriously punctured, perhaps by a bullet following a metaphysical trajectory fired from Marta’s gun. Time is running out. Soon the water barrel will be dry, the soul poured out of its vessel. Vittoria and Piero, Laura and Alec, a brief encounter lasting several weeks, time has run out, no time left, there’s no time at all.

From the opening scene of L'eclisse, people begin disappearing, dropping out like flies. Antonioni’s penchant for effacing his characters had been particularly striking in the disappearance of Anna in L’avventura. As already mentioned, freeze-frame the last shot of Anna and advance the film one frame at a time; Anna will literally, eerily dissolve before your eyes as Sandro and the surroundings remain. Later, in Blow-Up, again freeze-frame the Girl played by Vanessa Redgrave as she pulls an Anna-disappearing-act, vanishing near the sign of the store, “Permutit,” at 151 Regent Street (The store as indicated by an Internet posting [www.era-edta.org/proceedings/vol4/V4_007.pdf retrieved 6 February 2010] remains the Permutit Company Ltd., a vendor for a soft water product used in kidney dialysis). At the end of Blow-Up, Antonioni will wipe the Photographer from off the screen and the face of the Earth. In The Passenger, in their very first conversation, the Girl whose name has been effaced tells Locke-Robertson that “People disappear every day,” to which he responds, “Whenever they leave the room.” (“The Passenger was completed in September, 1973 and the next day Jack [Nicholson] boarded a non-stop flight from London to Los Angeles and reported to Paramount’s wardrobe department at eight that morning to begin costume fittings for his next film, Roman Polanski’s Chinatown.” [See Bibliography: Eliot, Marc.] In Chinatown, a movie specifically written by Robert Towne with Jack Nicholson and Nicholson’s style of speech in mind, the Nicholson character at one point picks up the phone and hears someone at the other end of the line say, “Are you alone?” The Nicholson character’s response: “Isn’t everybody?”) The theme of the Ephemeral runs throughout L'eclisse and much of Antonioni’s œuvre. In their final scene together, Vittoria and Piero declare their fidelity to each other promising to meet tomorrow and all days to come (Love, forever and a day). Such words are to be found under the heading, “Sweet Nothings,” in the Lexicon of the Void. Again, Born to Run, I wanna die with you Vittoria on the streets tonight in an everlasting kiss. Such a promise is broken as soon as it is made, bearing all the permanency of an oath written in sand at low tide (“. . . at lover’s perjuries they say Jove laughs.” Romeo and Juliet: Act 2, Scene 2.). Instead, the promise, once uttered, provides an absolute guarantee that Vittoria and Piero will never meet again. I take thee, to have and to hold, from this day forward, for better or poorer, in sickness and in health, till about 8 weeks do us part. In Ikiru, Kanji Watanabe does not suffer from such delusions. Moments away from death, swinging back and forth in the children’s park while it is snowing, Watanabe-san sings “The Song of the Gondola,” singing of that which Piero does not or cannot know:

Life is brief.

Fall in love, maidens

Before the crimson bloom

Fades from your lips,

Before the tides of passion cool within you,

For those of you who know no tomorrow.*

Aubrey Hallan in his trial for murder in I vinti exclaims in the courtroom: “The death of a human being is of no importance.” Is this the defense for the conclusion of L'eclisse: “The disappearance of a man and a woman is of no importance?”

Although not a conventional ghost story, there is a spectral quality to the film.36 The mystery and melancholy of a street, the anguish of parting, the enigma of a day . . . all titles of surrealist paintings by De Chirico, all paintings done in 1914 depicting the composizione metafisica of a cityscape somewhere at the end of the world, two small figures swallowed up by an urban landscape at the end of time (De Chirico’s metaphysical city would assume its concrete incarnation some 25 years later in the form of the Eur). The finale of L'eclisse, like the end of a mystery, thriller, or science fiction tale is a “surprise” one, an ending that despite so many prior hints and clues, denies our expectations and catches us off guard. The deflated conclusion of the film and the manner in which it is portrayed is so striking and unusual that I suspect it is the one feature of the film that most viewers might remember of a movie which they might otherwise consider quite forgettable. Indeed, the essence and fundamental value of the film depend entirely on its last several minutes. The unanticipated ending also speaks to Antonioni’s insistence that we may never truly know who anyone is or what they might be capable of doing. We may assume that, unbeknownst to us, Vittoria and Piero have been to some degree anticipating, contemplating, and war-gaming their eventual mutual double stand-up. This speaks to an entire off-screen world or “back-story of the mind” of both Vittoria and Piero that Antonioni has hidden from us. This seems to be particularly the case with Piero, a character who we discover at film’s end possesses an interiority camouflaged by his narcissistic superficiality.

Antonioni specializes in strong endings, whether the jarring act of adultery and ambivalent reconciliation at the end of L’avventura, the metaphysical game of tennis at the end of time and the world in Blow-Up, the miniature apocalypse which ends the world and Zabriskie Point, or the cinematographic prestidigitation which concludes The Passenger.* Although the ending of L'eclisse is a literal act of illumination, the justly famous conclusions of many of Antonioni’s films generally aim not to cast light upon their subject, but instead to reflect Antonioni’s penchant for shock, surprise, and twist. In this regard, Antonioni’s endings strive for “effect” as opposed to “illumination,” a trait that links Antonioni to earlier storytellers including Poe, O. Henry, or in a more contemporary light, Rod Serling. (To borrow a phrase from Wallace and Mary Stegner, Antonioni suffers from an “addiction to the tricky.”) It was during the 1950’s and 60’s when many children-- myself not included--were banished to bed at 8.00 p.m. as the “adult” programs such as The Twilight Zone were aired on television. (Ironically, many children were not permitted to see The Twilight Zone at that fateful hour of 20.00, but instead went to bed and retreated into sleep and the childhood cold war nightmares of nuclear apocalypse common at the time.) I can easily imagine the famous voice of Serling--fodder for impersonation by a generation of comedians--intoning in voice-over as the opening credits of L'eclisse roll:

“You unlock this door with the key of imagination. Beyond it is another dimension - a dimension of sound, a dimension of sight, a dimension of mind. You're moving into a land of both shadow and substance, of things and ideas. You've just crossed over into the Twilight Zone!”

As in a ghost story or murder-mystery, it is not long before Riccardo--the first character to appear in L'eclisse--disappears. (The empty frame in Riccardo’s apartment hints at his eventual disappearance, or the disappearance of Vittoria and Piero at the end of the film.) Like Anna of L’avventura (or Marion of Psycho), there is initial reason to believe that Riccardo will be a central protagonist in L'eclisse, and that he will not evaporate early in the action of the film. Instead, Riccardo vanishes, no residue remaining. (“Dead by the third act” is a cinematic term which refers to characters who absent themselves relatively early a film, often in an unanticipated manner.) A minute of silence is given to a dead stock market figure, heralding the no-show of another such figure, Piero, at the conclusion of the film. (After L'eclisse has concluded there will be an eternity of silence, for the soundtrack, the film itself, will have stopped. In such an eternal vacuum, we may if we wish call out to Vittoria and Piero, where have you gone? No answer will be forthcoming.) Who is Franco, but a phantom at the end of a telephone line? Piero calls out to that “other Franco” in his office, but he, too, has disappeared. As we have already seen, Piero’s first disappearance is after his first meeting with Vittoria at the water barrel, vanishing into thin air in the middle of the street. As soon as Marta and Vittoria find the lost dogs, Marta disappears, leaving Vittoria to walk alone at night in the Eur to the music of the clanging poles played by invisible musicians. Vittoria is similarly disembodied when late in the film she phones Piero, but does not speak. For Piero encountering such silence, there is no one there. Similarly, the incessant ringing of telephones in the office remains unanswered, left dangling. Where, in fact, have Piero’s co-workers disappeared to? The Drunkard is now dead, reminding us that almost all of Antonioni’s films depict death in some guise, whether murder, execution, suicide, or death by disease or accident.* Where has Vittoria’s father gone? The absence of Piero’s parents from their own apartment raises the question as to whether there is a hereditary predisposition to vanishing that Piero has inherited. Although we see Vittoria’s image reflected in a mirror in the first scene of the film, would such a reflection be seen if Piero himself stood before a mirror? (Relatively early in the film, Piero’s reflection, together with that of Vittoria, is clearly seen in a mirror in Vittoria’s mother’s apartment. Later, Piero does pass before a mirror in the seduction scene in his parent’s apartment, but it is now difficult to be sure if there is a reflection. Has Piero begun his disappearing act? In the light of day will he now cast a shadow?) Even the money lost in the crash seems to have disappeared, Piero not having the slightest idea as to where it has gone (adumbrating the more important question raised at the end of L'eclisse: where have Vittoria and Piero gone?).* Normally, in such cases money is merely reshuffled, not lost. In L'eclisse, however, it is as if even the laws of thermodynamics were themselves obliterated, that mass and energy can be forever destroyed, that Rome is not the Eternal City, Caput Mundi, but its alter ego, that of the City of Dissolution. Death, not in Venice, but in Rome. And finally it is the eve of the end, the vanishing point approaching when celestial bodies will be blocked out and eclipsed. Now you see it, now you don’t. Here today, gone tomorrow.*

When Antony dies in her embrace, Cleopatra, addressing no one, cries: there is nothing left remarkable beneath the visiting moon.

“Antony and Cleopatra”

Act IV, Scene 15

It is not just classical, Newtonian mechanics that shall be abridged, or even special relativity theory. A case of very special relativity theory appears to have been annulled, for in L’eclisse time itself appears not to have simply slowed down as the speed of light is approached, but to have, instead, become unaccounted-for. In L’eclisse it would appear that every scene in the film takes place either in mid to late July (the two respective scenes in the stock market) or on or about the other extreme of Vittoria and Piero’s approximately 8-week relationship, September 10. August seems to have disappeared; not the “lost weekend” of Billy Wilder, several days lost to the ravages of alcoholism, but in L’eclisse a much larger hole in time seems either “present” or “absent” depending on one’s point of view--a “lost month” attributable to some other more insidious and invisible pathology or rent in the very fabric of the absolute space-time continuum.

There are to my knowledge three secure time markers in L’eclisse. In each of the two scenes in the stock market we are able to clearly read the large calendar clock indicating, respectively July 10 (ostensibly the day Vittoria and Piero first meet) and July 21 (the day of the market . . . and car crash). The third time marker that bookends the film occurs in the coda when on extremely close examination one can read the date of the newspaper insert shot as 10 September 1961. There are three scenes between these two “bookends” that are ultimately of uncertain date: (1) Piero in his pyjamas reading the two newspapers, a scene itself flanked by two concurrent, brief scenes of Vittoria sitting on her bed and the abortive telephone calls she makes to Piero as he is reading the papers and preparing a bedtime medication of some sort. (Unfortunately, I have never been able to clearly visualize the date of the two papers that Piero reads.); (2) Vittoria and Piero’s second meeting at the construction site, after which they go to the apartment of Piero’s parents to presumably make love; (3) The scene on the grassy knoll with the strange building in the background. It has been pure speculation on my part to assume that scenes #1 and #2 above occur early in Vittoria and Piero’s relationship—probably in late July—and that scene #3 above occurs towards the end of their relationship, probably in early September. I must emphasize that I cannot prove this to a certainty. My reasoning is crude but, unfortunately, may accurately conform to common human behavior: Piero isn’t a guy who is going to wait long before he tries to get into the panties of a woman he is stalking. (He makes a pass at Vittoria in her childhood bedroom in her mother’s apartment on what may be the second time he ever sees her.) Likewise, he isn’t the type to stick around when the bloom starts to come off the rose; he’s out of there when he’s had enough sex and any emotional demands are made of him. This line of reasoning leads to my speculating that the scene in which he takes Vittoria to his parent’s home is in late July, relatively early in Vittoria and Piero’s relationship. Similarly, it is clear that Vittoria and Piero are having relationship problems when they are on the knoll, which, if my line of speculation is correct, means the scene takes place near September 10, the time when he will abandon her. (I very much doubt that Piero knows that he, too, will soon be abandoned—for different reasons—by Vittoria.) It is, however, of inestimably greater importance—not where Vittoria and Piero are in August of 1961—but where they are after the 10th of September, 1961.

Ultimately, there may have been a trivial reason for Vittoria and Piero seeming to drop out of sight, out out of mind, during August. L’eclisse was not shot in strict chronological order, in part because it was necessary to shoot the stock market scenes during the month of August when Rome goes on holiday and the market was relatively available for invasion by a film crew. Although principal photography began in July, 1961, it was absolutely imperative for Antonioni to shoot the critical stock market scenes in August. It is highly likely that the calendar clocks of the stock market, time itself, were reset to promote the false verisimilitude of movie-making. Although the calendar clocks indicate dates in July, the market scenes were shot in August. The same might be said of the date on the newspaper in the coda, but I have never investigated this. All movies are essentially white lies or worse, that in the best of cases—such as L’eclisse—are struggling to achieve an artistic truth.

“Ferragosto” refers to the mid-summer period in Italy when virtually the entire nation goes on holiday, ostensibly to celebrate August 15, the day traditionally ascribed to that of Mary’s Assumption. Such a tradition [Feriae-Augusti) has roots in pre-Christian times when the goddess Diana and the cycle of fertility and maturity were venerated. In 1961, the phenomenon of Ferragosto permitted Antonioni and his film crew to invade the vacant Roman stock market to shoot the relatively long and complex market scenes. Antonioni is fond of ellipses, but in the case of August, 1961, an especially gigantic hole appears in the middle of L’eclisse where Vittoria and Piero, the entire film, go temporarily missing. Again and again, the question arises: where are Vittoria and Piero? On a yacht in the Tyrrhenian Sea sailing amongst the Aeolian Islands? In Taormina at the San Domenico Palace Hotel? Or did they hop on a jet plane at the new airport at Fiumicino and spend their last, full month together, a Rhapsody in August (1991), in Nagasaki, meeting at 20.00 or, perhaps, 11.02, at Nagasaki’s counterpart to the intersection of Viale della Tecnica and Viale del Ciclismo, the hypocentre at the address, 7-8 Hirano-machi? In the grand context of L’eclisse, the probability that Vittoria and Piero have departed on an August vacation from Rome for parts unknown is less important than--given the ever present proximity of death in the film--the merciful chance that Death, too, may have taken a holiday.

A consequence of the special theory of relativity is that two events happening in two different locations that occur simultaneously to one observer, may occur at different times to another observer (lack of absolute simultaneity [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absolute_simultaneity] retrieved 28 January 2008). Is this the reason why we cannot see Vittoria and Piero at the end of L’eclisse?

After the market crashes, a provident moment occurs. Piero is in the small Bar della Borsa fronting the Piazza di Pietra, directly across from the Borsa. Piero haphazardly glimpses Vittoria--through a curtain-like shroud of black beads separating the bar from the street--as Vittoria, outside the bar in the piazza studies with intense interest the enigmatic doodle of daisies. This “accidental” bumping into each other is the decisive moment when the orbits of two celestial bodies intersect, carom, and kiss--as if in a game of cosmic billiards--setting in motion a series of movements that will ricochet on the playing field of destiny. It is this glancing encounter, one orb briefly caught in the gravitational pull of another--one billiard ball striking in a “dead ball shot” another billiard ball striking yet another billiard ball in a chain reaction of causality--that will lead collision-by-collision till the moment when, finally, the cue ball drops inevitably into a corner pocket that is a water barrel tucked in the recess of a small solar system circling a relatively little star called the Eur. Scratch. It is at the moment of this critical, accidental collision that--of all the conversations Vittoria and Piero might have had, of all the small talk, of all the silly things Vittoria and Piero might have talked about--Vittoria stubbornly pursues the ultimate, sublime question: “Where has the money gone in the Crash?” Four times, Vittoria--in one way or another--asks Piero, where’s the money? And four times, Piero--in one way or another--doesn’t answer her. Vittoria is like a vigorous prosecutor, engaging in the dogged cross examination of a witness, who at the end of day, even the Supreme Judge of the Universe--under threat of contempt of a divine, superior court--cannot compel to answer.

Vittoria: Ma. Tutti questi miliardi che si perdono in borsa, dove vanno a finire?

(But, all this money that was lost in the market, where is it all going to end up?)

Piero: Da nessuna parte.

(Nowhere.)

Vittoria: Beh, ma quando uno vince, li prende i soldi?

(But, when someone wins, they get the money?)

Piero: Sì.

(Yes.)

Vittoria: Allora, li prende da chi perde?

(Then the winner takes the money from the loser?)

Piero: Non è così semplice.

(It isn’t as simple as that.)

Vittoria: Ma . . . Quando uno perde, i soldi dove vanno?

(But . . . when someone loses, where does the money go?)

Piero: (Silence; Piero shrugs his shoulders, as the Drunk will soon do in his existential gesture of incertitude in front of Vittoria’s apartment.)

Vittoria’s interrogation of Piero as to where the has money gone is reminiscent of another investigation in which trying to follow the money trail may lead to the solution of a crime:

Bob Woodward: The story is dry. All we've got are pieces. We can't seem to figure out what the puzzle is supposed to look like. John Mitchell resigns as the head of CREEP, and says that he wants to spend more time with his family. I mean, it sounds like bullshit, we don't exactly believe that...

Deep Throat: No, heh, but it's touching. Forget the myths the media's created about the White House. The truth is, these are not very bright guys, and things got out of hand.

Bob Woodward: Hunt's come in from the cold. Supposedly he's got a lawyer with $25,000 in a brown paper bag.

Deep Throat: Follow the money.

Bob Woodward: What do you mean? Where?

Deep Throat: Oh, I can't tell you that.

Bob Woodward: But you could tell me that.

Deep Throat: No, I have to do this my way. You tell me what you know, and I'll confirm. I'll keep you in the right direction if I can, but that's all. Just... follow the money.All the President's Men (1976)

Vittoria, without any prompting from anyone—let alone a version of “Deep Throat” all’Italiana—is trying to follow the money. Unlike Bernstein and Woodward, however, Vittoria is not interested in some intricate variety of forensic accounting that might require a team of journalists, accountants, attorneys, financial analysts, and private investigators to solve some ultimately “trivial” issue as to whether the President of the United States has committed a crime. Vittoria wants to know where the money has gone for reasons that are much simpler, more naïve, and ultimately much more profound. Later, we shall see that following a girl as opposed to following a money trail, may lead to the solution of a puzzle concerning The Passenger (vide infra, Endnote #19, “Cherchez la femme.”)

Piero is as indifferent to Vittoria’s interrogation as he was to Vittoria’s showing him the doodle of daisies, as indifferent as Piero ultimately was to the stock market crash, as indifferent as Piero will be to the impending death of the Drunk. After all, to Piero, Vittoria is just a little girl, asking a lot of childish questions about things she knows nothing about. It is at that point that Vittoria says, “Beh, ciao. Basta.” (OK then, enough already. So long.”) Too late. One billiard ball has struck another and Piero offers to accompany Vittoria to her mother’s apartment. And then, Piero will later carom to the street just beneath his office, barely missing his encounter with another billiard ball, the Bestiola. And then the cue ball will be struck with a little English, in turn striking two other balls, as Vittoria and Piero will spin off their axes, and hurl in an ever expanding universe to a southern suburb of Rome called the Eur with its humble sign of life, a little body of water, the surface of which is marred by a broken piece of wood and a matchbook, not far from Ostia, Fregene and the sea, and then . . . Stop. No more. Maybe, Vittoria shouldn’t have accepted Piero’s invitation to join him in the Bar della Borsa, sparing them, us, everyone, an eventual disillusionment of catastrophic proportion that wrings the heart and collapses the firmament itself, creating a black hole. If Vittoria’s orbit was such that she hadn’t been studying the diagram of the universe in front of the bar, then, maybe, just maybe, L’eclisse wouldn’t have had to happen in the first place and we could have all been spared a world of pain.

And all the while, during this grand inquisition by Vittoria that will lead nowhere, answer no questions, result in no conclusions, Vittoria does not know that she and Piero, too, will soon disappear, and that no one will ever care to ask--as Vittoria had of the stock market crash--Ma. Questi due che si perdono, dove vanno a finire?

The money lost in the crash--like so many things in L’eclisse--seems to have disappeared. (Piero may be the type of man described by Oscar Wilde as the all-knowing broker “who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing” [my italics]; Piero certainly has no conscious idea that the void yawns before him.) In the 1959 Walt Disney 27-minute cartoon, Donald in Mathmagic Land, Donald Duck is better at explaining the physics of billiards than is Piero at explaining where money comes and goes in the stock market. Vittoria wants to know what’s happened to the money; it is this seemingly juvenile curiosity that adumbrates the truly sublime question that is hurtling our way like an irresistible object in a collision that we will never be able to avoid: at the end of L’eclisse--after all is said and done--the only question that may ever really matter becomes:

Where are Vittoria and Piero?

Vittoria is the only largely sympathetic figure in all of L'eclisse. She is an inhabitant, however, of a hellish world whose beings are unconscious--sleepwalkers, if you will, à la Broch: the terminally self-absorbed. The worst of them are condemned to a lower level of the Inferno, the Borsa, engaged in a rabid pursuit of money, the acquisition of which will not lead to redemption. Such is the contagion of the Borsa that Lane remarks in his book on L'eclisse (p. 18) that during the shooting at the Rome stock market for 15 days during August, 1961, many of the film’s company played the market.

Mal dare e mal tener lo mondo pulcro

ha tolto loro, e posti a questa zuffa:

qual ella sia, parole non ci appulcro.

(Wrongness in how to give and how to have

Took the fair world from them and brought them this,

Their ugly brawl, which words need not retrieve.)

The Inferno, Canto VII

(translation by Robert Pinsky)

Antonioni recreates the infernal ugliness of the Borsa in so vivid a manner that Steven Jacobs has written: “Since Dr. Mabuse. Der Spieler [1922], the stock exchange as a teeming mass of hooting and gesticulating individuals [has never been] pictured this convincingly” (see Jacobs, Steven. “Between E.U.R. and L.A.: Townscapes and the work of Michelangelo Antonioni” [p. 342]). Towards the tragic conclusion of Godard’s Le Mépris, Paul laments:

“Why does money matter so much in what we do, in what we are, in what we become, even in our relationships with those we love?” This is not a question of making enough money to exist, a question that Tolstoy raised when he asked, “How much land does a man need?” (and that Joyce regarded as “the greatest story that the literature of the world knows”). Even Vittoria, the least covetous person in the universe of L'eclisse, recognizes the fear of being poor. In her mother’s apartment Vittoria specifically refers to her mother’s fear of “la miseria,” to which Piero responds with uncharacteristic insight: “Fa paura a tutti.” / “We are all afraid of poverty.”* The predominant emotion shown by the investors who huddle like threatened animals in Piero’s office after the crash is that of fear (which makes the obese investor who had lost so much money even more enigmatic in the superficial calm he displays as he composes a doodle of daisies). It is a particular subset of fear, the variety that causes people to jump out of tall buildings when markets crash and money is lost. But L’eclisse is not about lost money, but about lost love. The phenomenal feat of movie directing that Antonioni performs in his two scenes depicting the circus minimus of the Borsa are but side shows to the main act to take place beneath a small light illuminating the principal proscenium of L’eclisse, a dirty water barrel at a construction site, the real Luna Park of the film. At the end of L’eclisse’s day Piero will have lost something much more precious than 50 million lira. And, as is the case with the money lost in the market crash, he will have no idea where love has fled. Worst yet, Piero will not be able to turn the tables and ask Vittoria—as she had once asked him regarding the money in the crash—what has become of their love? By then, Vittoria will be gone forever. Piero’s loss will not be recouped by his seeking the sage, financial advice of another broker—one who will hopefully treat Piero in a more kindly manner than Piero treated his own clients—but will haunt Piero in a more biblical sense for all of the remainder of his allotted days. By the time we arrive at Il deserto rosso this fear will have generalized--as Giuliana herself says--to a fear of “everything.” For the trembling human being who is Giuliana, “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” The avarice of the Borsa, however, has become pathologic, pestilent, a scourge. The horror of the Borsa--this particular small corner of hell--resembles that of ghouls clamoring in a Boschian nightmare. Impending doom hangs over such a world, for only the coming of Fire or Flood can hope to cleanse such wickedness. It is no wonder that Vittoria turns her gaze away from the ugliness of Man, to look instead upon trees. In this world there are no other humans with whom she might couple. And then, there is the End. The final moments between Vittoria and Piero in a film that begins and ends on the same note, that of rupture. The two lovers make plans to meet tomorrow and all days to come, a pledge that in an Antonionian universe is bad manners and even worse luck (as in the expression, “I’ll love you to the crack of Doomsday,” a loving promise that undoes itself in the recitation). It was imperative for Antonioni to underline this commitment, for it is this pledge that will ignite the final countdown to the apocalyptic conclusion of the entire film when the oath to meet forever again is forever broken. (The narrative principle is an old one, peripeteia [Περιπέτεια], a “reversal of fortune,” emphasized by Aristotle in his Poetics as among the most important elements defining tragedy; in their final moment together, Antonioni elevates Vittoria and Piero to the sublime so as to make their tragic fall only the greater, inspiring fear, inspiring pity.) As compared to the desultory and halfhearted proposal of marriage that Piero makes while he and Vittoria are on the knoll in the Eur with the strange, church-like building behind them, the proposal to meet forever again—the faces of Vittoria and Piero, side-by-side staring out at us from one void into another—is one of the most tender, lyrical moments in all of Antonioni’s films, an epiphany of romantic lyricism rare in his work. The commitment is a reciprocal assertion of undying love, a compact with eternity. Cross my heart and hope to die. (Potessi mori’ se non è vero.) Vittoria and Piero’s vow to meet for all days to come is ultimately a betrothal, a commitment that may be likened to the biblical pronouncement of Ruth 1:16-17 (King James Version): And Ruth said, Entreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge . . . Where thou diest, will I die, and there will I be buried: the LORD do so to me, and more also, if ought but death part thee and me. ותאמר רות אל תפגעי בי לעזבך לשוב מאחריך כי אל אשר תלכי אלך ובאשר תליני אלין עמך עמי ואלהיך אלהי׃ באשר תמותי אמות ושם אקבר כה יעשה יהוה לי וכה יסיף כי המות יפריד ביני ובינך׃ Vittoria and Piero have taken an oath (schvua), binding their souls together with an eternal bond. And . . .

When a man takes an oath he’s holding his own self in his own hands. Like water.

And if he opens his fingers then—he needn’t hope to find himself again.

A man for all seasons – a play in two acts. (Page 140). Robert Bolt.

New York City: First Vintage International Edition, 1990.

But, in this instance it shall be Vittoria and Piero who will together open their intertwined fingers and lose the water of life as if a sacred vessel or a barrel at a ramschackle construction site had been breached, the terrible consequence being that they will never find each other again. Insofar as Vittoria and Piero are in all likelihood Christians (although Piero’s parents live in the old Jewish ghetto), their vow to meet for all days to come may resonate more appropriately, more ironically with the New Testament rather that with the “Old,” the Torah. For as Jesus says to the Disciples in John 13: Whither I go, ye cannot come. Or, as Vittoria and Piero may be saying to each other in their mutual “double stand-up” at the conclusion of L'eclisse : Whither I go, follow me not.

This moment, Vittoria and Piero together for what will be the last time in their lives, every indication suggesting that both they and a weary world shall soon die—making commonplace romantic promises—when, instead, they might be better served by performing the extreme unction, anointing one another not with water from a font or stoup in front of one of the nearly thousand churches in Rome, but with the stagnant residue of a barrel in front of a construction site in the secular Eur. And after Vittoria and Piero dip their hands in the barrel and touch with the utmost tenderness each other's face, their foreheads, the lids of their eyes, their very lips, reciting not one of the customary sacraments, but instead:

Whose disappearance will fill you with despair? Whom can you not live without? Whom do you painfully long for? Which of your dead hangs over you daily? Show me where and how death has mutilated you. Where are your wounds? Whom would you pursue beyond the gates of death? (Saul Bellow. The Bellarosa Connection.)

The disparity between what is promised and what will be received could not be greater. Yes, in L'eclisse the market has crashed—but as in a fall from grace—so, too, have Woman and Man. The market value of eternity has been devalued and plummeted from an all time Dow Jones Industrial Average high of forever to no time at all. Although the sacrament of marriage is understood as persisting beyond the grave into some heavenly, immortal afterlife, for Vittoria and Piero, it is as though they had just exchanged vows and been married in the Las Vegas wedding chapel of hell. They shall not dwell together in the same house in this life let alone in the sweet hereafter. Exiting the chapel’s portico, Piero turns one way and Vittoria another, never the twain to meet again.

To compound this existential gaffe of affirming a contract that cannot be kept, Vittoria and Piero do not utter the word “goodbye” to one another, but instead repeat the same script that Piero and the Bestiola have already followed, as well as Vittoria and Riccardo before them.* It is the casual linguistic token of parting--a simple “goodbye”--and not the hazardous declaration of eternal love, that commonly implies we will see each other again. In Italian , the word, “arrivederci,” emphasizes this contract, for “arrivederci” is both a linguistic token of farewell and a promise to see one another again, something Vittoria and Piero will never do. From a psychological perspective, the reciprocal refusal of Vittoria and Piero to say goodbye to one another may reflect their aversion or inability to directly confront each other with their final parting. This is, of course, a variety of the common cowardice exhibited when a young man asks a young woman (or vice versa) for her telephone number and--after writing on a scrap of paper the incorrect telephone number--the woman enthusiastically intones, “Yes, please do call.” (something akin to what the Photographer of Blow-Up actually experiences at the hands of the mysterious woman of Maryon Park). From the lyrical or stellar perspective, the reciprocal refusal to say goodbye reflects the separation of two star-crossed lovers, a distance that in an Antonionian cosmos may never be annulled.

There is also the question as to whether Vittoria and Piero (both) knew at the time of their pledging to meet forever again as to whether they had any sincere intention of actually doing so. While staring outward at us declaring eternal devotion, their tragic Janus-like masks side-by-side, had Vittoria and Piero achieved—behind each mask—a recognition that their two names, like those of Vittoria and Riccardo or Piero and the Bestiola, were not inscribed side-by-side in the Book of Life? As already discussed, Antonioni’s characters—particular the men—have little insight and are not psychologically-minded. Aristotle, again in the Poetics, wrote that in addition to peripitea, that anagnorisis (Ἀναγνώισις)—a recognition or discovery by a character of their true state—was a critical factor in the elaboration of the tragic narrative. (Can an individual with a significant narcissistic personality disorder such as Piero ever achieve anagnorisis?) Indeed, Aristotle wrote that anagnorisis preceded peripitea (“[anagnorisis is] a change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune” [Part II: Section A.3:d. “Recognition”]). Regardless as to whether Vittoria and Piero had knowingly uttered false oaths, such knowledge on their part is not accessible to we viewers and—as is true of the “interiority” of all characters in film and the sub-conscious itself—is ultimately off-screen (as all film criticism is off-screen, a position or reference point that is a major epistemological snare for said criticism).

And then, there is the final embrace--not of lips, but of limbs--Vittoria’s fingers briefly tracing the outline of Piero’s lips, their two heads side by side, gazing not into each other’s eyes, but outwards in the direction of ourselves and cinema’s fourth wall. (As they stare outwards at us, Vittoria mouths an unspoken word, perhaps, “amore,” an utterance Piero cannot hear nor see, a tragic mime.) Vittoria turns and leaves, no kiss nor verbal exchange of goodbyes, not an addio, arrivederci, nor even a ciao. (If you doubt that Antonioni carefully choreographed this final dance of despair, that he did not carefully obliterate both of the two standard signs of leave taking--two pairs of lips touching and the utterance of a goodbye--then, regard the photo on p. 47 of Biarese and Tassoni showing Antonioni directing the marionettes of this parting.) The refusal to say goodbye and the denial of a kiss, following an agreement between Vittoria and Piero to meet on all-of-their-tomorrows-to-come, seal their fate. The end is near. Vittoria and Piero will never meet again.

The final minutes of L'eclisse are a coda or epilogue. And yet, such a coda is not an afterthought, but the end point, period, exclamation mark that the entire film has been slouching towards. For some viewers, the final minutes of the film represent a twist--a highly dramatic and stunning surprise ending that suddenly gives meaning to all of the ostensible tedium that precedes the explosive revelation that both Vittoria and Piero will not keep their appointment. (This “twist” is not an allusion to a Chubby Checker dance suggested by the title song of L'eclisse, “Eclisse Twist,” although the lyrics of the song--like most pop music--may refer to lost love.) It is a startling artistic achievement that a moment when nothing happens may be so dramatic. Such an ending is characteristic of the greatest of Antonioni’s films--L’avventura, Blow-Up, The Passenger--all films in which a stupefying finale occurs that is so strangely quiet. (Zabriskie Point’s ending is as loud as loud may be, but must also be included among Antonioni’s films that have an unanticipated climax that sucks the air from out one’s lungs.)*

Prior to the coda of L'eclisse, the film has in a sense already ended, and this epilogue--like all epilogues--is a kind of afterlife, a stage in which the actors have vacated the theater, leaving the camera and the audience alone to commune. We and the camera have shown up for the 8 p.m. appointment, and as the machine which records images waits in vain, its attention increasingly wanders, as it becomes an autonomous observer. This is, of course, a poetic observation, for the camera’s attention has never really wandered nor achieved a life of its own, not even for a second. In the world we inhabit outside of L'eclisse, the camera is a thing and not a living creature. The camera has always been a mechanical extension of Antonioni’s eye, which in turn has always been directed by Antonioni’s mind. He looks at ants crawling on the bark of a tree, at the headline of a newspaper, at strangers pointing to the sky. It his gaze that serially dissects the face of an old man or finally fastens at sunset on the illumination of a streetlight. His consciousness is fused, however, with that of another, a fictional character of his own creation, Vittoria, and as the camera ponders the contents of the water barrel, its matchbook and piece of wood, this image is one that Vittoria, if she were alive, would seek out.

All of the shots of the coda are limited not only to the Eur, but to the relatively small section of the Eur centered on the construction site. No shots are presented, for example, of prior scenes that took place in the historic center of Rome such as the Piazza di Pietra or to certain sites in the Eur which had been shown previously such as the Palazzo dello Sport. Likewise, the coda is not a mere return-to or recapitulation-of the prior sites in L'eclisse where we had previously seen Vittoria and Piero. Indeed, new, unidentified characters are fleetingly introduced in the final minutes of the film. The camera’s seemingly aimless wandering is volitional and has as its initial goal--at least in the opening minutes of the coda--a progressive approach from the general to the particular, from the periphery to the center, a march from the opening shot of the coda with its long shot of the half-finished building with the water tower in the far background, to a succession of shots finally zeroing in on the matchbook and piece of wood. (This opening long shot occurring at the beginning of the coda of L'eclisse is the only such “establishing” shot of the half-constructed building in the entire film; for the first time we appreciate the building’s proximity to the water tower, a tower that we last saw in the beginning of the film at Riccardo’s apartment, an image as such that reclaims Riccardo from the dead and links him to the end of the film.) The entire momentum of the first minutes of the coda concerns this movement from the macro to microcosm. Following the elementary rules of painting and stagecraft, all lines converge from the periphery of the screen to a final obsession with the center of L'eclisse, the water barrel, now somehow ruptured and bleeding to death. Thus, the arc of the water sprinkler, the movement of the nurse and pram, the prancing of the sulkey, and the zebra lines of the intersection carry our line of sight to an X-marks-the-spot, the point by an anonymous water barrel and the dead end of L'eclisse where Vittoria and Piero have met twice before, proof that things don’t always come in threes, due senza tre. The final shot of the half-finished building and water barrel occurs in darkness immediately before the camera shifts to the sudden and jarring final contemplation of the streetlight. Above the barrel is a sign that we cannot read, above which in turn is a naked light (not a streetlight) at the construction site.37

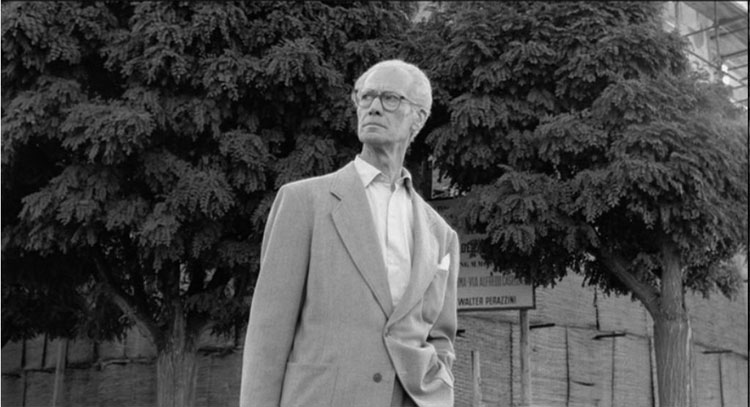

The sign behind the thirteenth man

When one ponders this simple light, asking why anyone would place such a light at that precise spot, the thought arises that this light does not appear meant to illuminate the street nor serve any obvious purpose (such as to illuminate the sign at night). Instead, it would seem that Antonioni--not the City Bureau of Works nor a construction company--had presumably placed the light above sign and barrel to serve a theatrical end. The shaft of light which places the barrel in prominent relief against a background of darkness comes essentially from a stage or focus light meant to illuminate this undistinguished, final stop of L'eclisse. In this regard, the light—to employ a term from the glossary of cinematography—constitutes a kind of “unmotivated lighting.” Its function is not to assist pedestrians--“extras,” as it were, encased within a fictional world--to navigate their way in the dark night beside a construction site, but to assist we the audience as we gaze upon a kind of black hole, a water barrel into whose dark, swirling confines a broken piece of wood, a matchbook, and all of L'eclisse have been sucked into and disappear.*